Over-the-Top Mayan Tomb Reveals Man Who Lived a Bit Too Large

There’s a stereotype among celebrities and lottery winners that when they first get successful they spend money indiscriminately and buy huge mansions to live in. Later, if they fall on hard times, the cars are sold and the property falls into disrepair. As the most expensive, and often overpriced, purchases the houses are the often the last thing to go. They’re a testament to why you shouldn’t assume that good luck should last. Archeologists recently unearthed an ancient example of this at El Palmar (in modern-day Mexico): the temple tomb of an ancient ambassador who had obtained a position of great influence and prestige before falling from grace and dying in poverty.

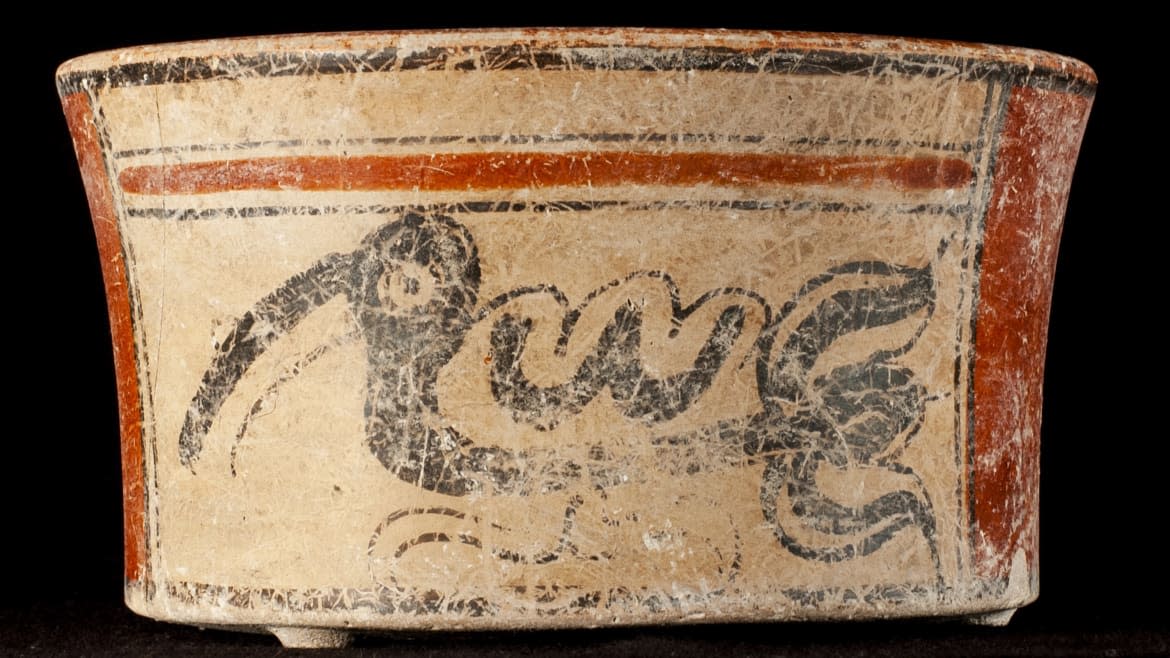

Archeologists Jessica Cerezo-Román and Kenichiro Tsukamoto were excavating a temple when they unearthed the tomb of Apoch’Waal beneath the floor of a platformed structure. The process of building the platform was extremely costly and even ostentatious—only elites could afford to invest this much money in afterlife architecture. Cerezo-Román and Tsukamoto were expecting, therefore, to find an equally elaborate tomb adorned with expensive grave goods. They were surprised to find only two decorated pots. A grave-robber might have been disappointed, but the archeologists were intrigued. What was such a humble tomb doing in such a prestigious location?

Piecing together the evidence from the hieroglyphic inscriptions that decorated the stairs up to the platform with Apoch’Waal’s physical remains they began to reconstruct his life. The results of their work were recently published in Latin American Antiquity. The epigraphic evidence suggests that that the man was a Mayan standard bearer, an important political and economic diplomatic figure in ancient Mesoamerica.

As a boy, his remains show, life may have been a bit tough. The lasting effects of malnutrition or illness remain in his bones, but he had been cared for in the Mayan way: the back of his skull had been subtly reshaped through prolonged contact with a flat object as a child. It was a technique designed to make him more attractive. At some point during puberty he went through a painful dental procedure for elites designed to increase (or display) his social status. Holes were drilled in all of his upper front teeth and decorative implants made of valuable pyrite and jade were placed inside.

The procedure, like braces (our own rite of passage for affluent adolescents), was deeply uncomfortable but it may have signified his entry into the elite. It may have happened around the time he inherited his position as “standard bearer” from his father and became a diplomatic emissary.

His story reaches its climax in 726 A.D., though, when Apoch’Waal’s career began to take off. That summer he travelled hundreds of miles, with standard in tow, to Copán in modern-day Honduras to foster ties between the king of Copán and his own ruler, the king of Calakmul. The resulting alliance was a high point for Apoch’Waal; when he returned to his hometown he commemorated the event by building the temple and platform for himself. The platform would have been the setting for priestly rituals performed before larger audiences and only the wealthy were able to afford to build them.

The story of the successful diplomatic mission to Copán is told on the hieroglyphs that adorn the stairs, but what happened next is difficult to discern. Why were no valuable items such as jewelry found in his tomb?

The only answer is a fall from favor and decline in affluence. In a press release, Tsukamoto, an assistant professor at the University of California, Riverside, said that “The ruler of a subordinate dynasty decapitated Copán’s king 10 years after his alliance with Calakmul, which was also defeated by a rival dynasty around the same time.” The sudden change in political fortunes and the shifting political allegiances that followed led to an economic downturn that may have left Apoch’Waal out in the proverbial cold. Small communities like that at El Palmar would have felt the economic effects of political instability the most.

This loss of status is mirrored by Apoch’Waal’s declining health in the later years of his life. An examination of his bones reveals that Apoch’Waal developed arthritis in his right elbow, left knee and ankle, and hands. The stiffness and pain may well have been caused by kneeling on the platforms of Mayan rulers, or the long hours holding the standard on the road, but the consequences would only have been felt later in life.

He also began to suffer from dental problems. Prior to his death he had lost a number teeth due to gum disease and had lost one of the jewels that had been drilled into his teeth. The fact that the precious stone was not replaced offers further support for the idea that his socioeconomic status slipped after the king of Calakmul, his former patron, had been deposed. Despite his fall from power and privilege, when he died—sometime between the ages of 35 and 50—he still had the right to be under the extravagant platform he had built.

His final years, we can deduce, were spent in pain. The joint pain and near constant toothaches would have reduced him to eating a diet of soft foods and made getting around painful and slow. The story of his fall from favor was written in his asymmetrical smile. Though he had enjoyed many of the privileges of the elite over his life, even elite diplomacy was physically strenuous and difficult. And the debilitating effects of chronic pain did not spare the wealthy.

For historians, the discovery is an important one. Monuments like this usually only survive for the ancient royal elites, whose tombs speak of wealth and happiness. Apoch’Waal’s story is rare and complex. Here we learn more both about the lifestyle and hardship of elite diplomats and also of the precariousness of political favor and good fortune. The hieroglyphics on the stairs document his ascent to power, but his sparsely decorated tomb, joint damage, and unrepaired tooth tell the story of his decline.

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.