They overcame police dogs and beatings: Civil rights activists from 1960s cheer on Black Lives Matter protesters leading new fight

WASHINGTON — Jordan Simmons noticed the young Black woman next to him had stopped chanting, breaking down in tears. She had been leading fellow protesters outside the White House to repeat the names of Black Americans killed by police.

Simmons, a usually quiet 18-year-old from Laurel, Maryland, turned to his mother.

“I want to do a chant, but I’m nervous,” he said.

He was in the crush of the crowd surrounded by people -- Black, white, old, young.

“You take the lead and I’ll follow,” Elaine Simmons coaxed.

“Hands up! Don’t shoot!” he chanted. “Hands up! Don’t shoot!”

Simmons doesn’t know how many times he shouted. He just remembered the crowd repeating the words. “It felt like it was the right moment,” he said.

As thousands of young people across the country protest the deaths of unarmed Black Americans, veterans of the 1960s civil rights movement say they’re disappointed another generation must take to the streets over injustices they fought against 50 years ago: police brutality, discrimination, health disparities.

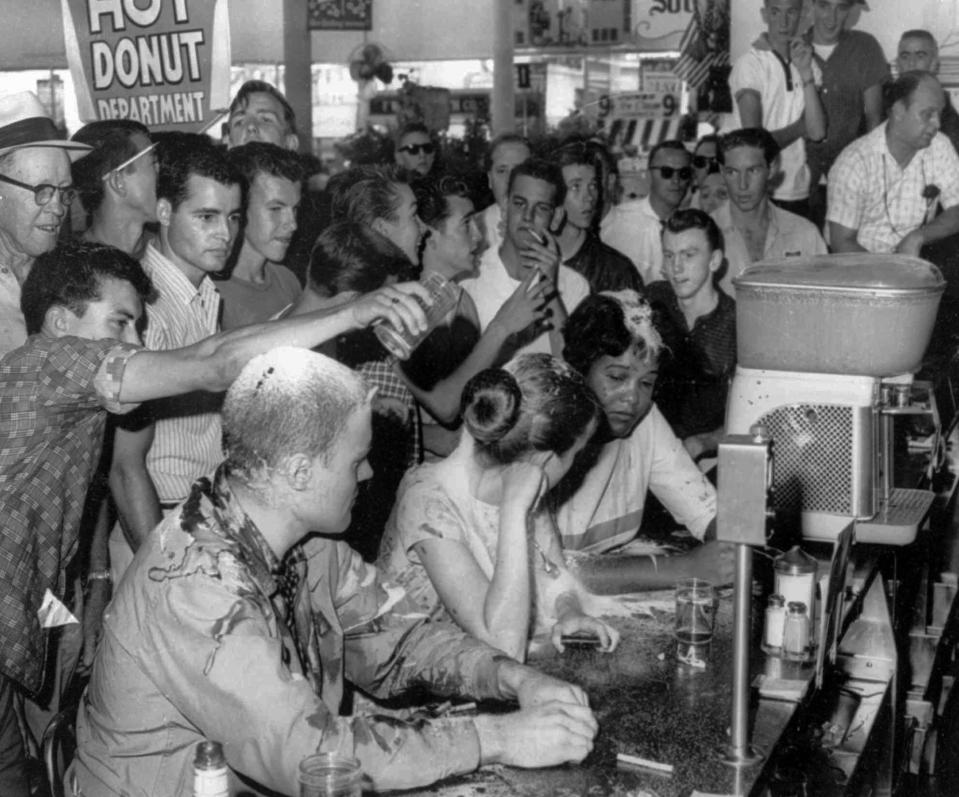

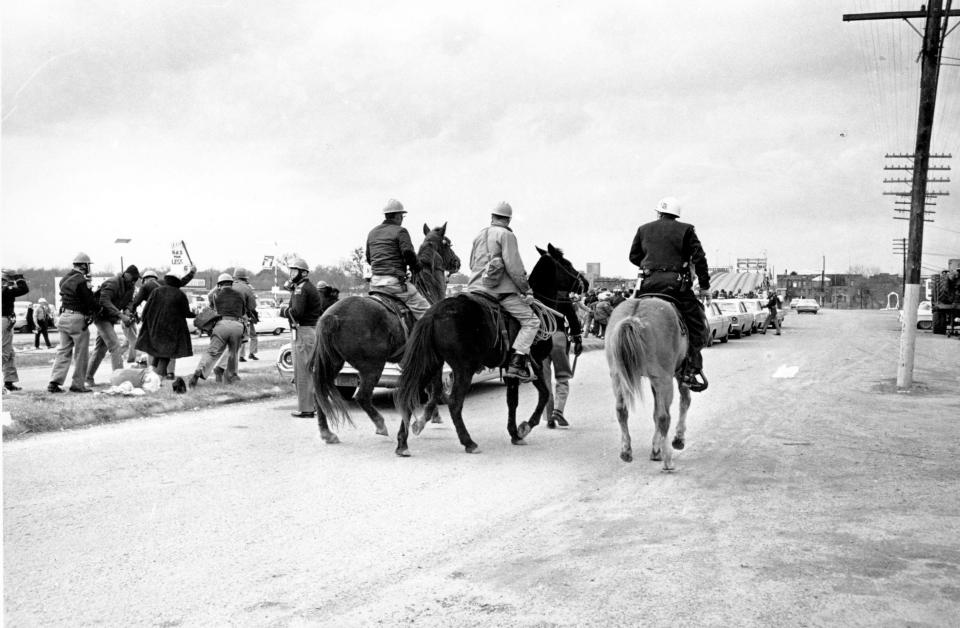

The battlefield is different. Back then, there was no Twitter or Instagram to summon others. Demonstrators faced police dogs, fire hoses, beatings and even death.Today's protesters sometimes face rubber bullets, tear gas and tasers.

Still, the veterans praised this generation of protesters, some young enough to be their grandchildren or even great-grandchildren, for showing up in force to demand justice and police reforms.

“What’s amazing to me is these young people who are the age we were … you see the same passion and that same sense that they really do believe they can change things,” said Judy Richardson, 76, who worked for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in Alabama, Georgia and Mississippi from 1963 to 1966.

The Deep South was at the heart of the civil rights movement and hostile territory for activists. Young people, many of them college students, joined protests there that lead to landmark voting rights and civil rights legislation.

John Koroma, 24, acknowledged the fight was harder, even deadlier, for his predecessors. Koroma joined hundreds of protesters demonstrating against systemic racism recently outside the White House. He returned later to take pictures in his graduation cap and in front of a Black Lives Matter banner.

“They’re certainly the trailblazers,’’ he said of civil rights era protesters.

Koroma, who earned his master’s in applied economics from the University of Maryland, said recent protests were sparked by the deaths of more unarmed Black men, including George Floyd, a 46-year-old man who died in police custody in Minneapolis after a white officer held his knee to his neck.

"I was fed up,” Koroma said.

Older activists join Black Lives Matters protests

Young protesters are not alone.

Frank Smith, 78, joined two recent protests in Washington, D.C., and said other civil right veterans are also on the front line.

“I got bad knees and a bad back, but every chance I get I hobble along and try to keep up,’’ said Smith, who served as a SNCC field secretary in Mississippi for six years in the early 1960s. “I got a couple of good marches left in me.”

Smith said today’s efforts are not like working in the Mississippi Delta or walking 56 miles during the Selma to Montgomery civil rights march in Alabama in March 1965.

Veterans went to states like Alabama, Louisiana and Mississippi to help register Black Americans to vote and fight to integrate schools and public places like bus stations. The late Marion Barry, the first chairman of SNCC and former mayor of Washington, D.C., once called his home state of Mississippi “the last bastion of apartheid.”

The veterans pushed up against a white power structure that included not only politicians but police and the Ku Klux Klan. Sometimes they were the same people.

“The mob would attack you and then the police would come and arrest you and charge you with disturbing the peace,’’ recalled Smith, now director of the African American Civil War Memorial Museum.

Smith said he didn’t sleep much, afraid attackers would set his home on fire or shoot into it.

“We lived in fear of our lives 24 hours a day,’’ he said.

Still Smith, who later served as a councilman in Washington, D.C., said young protesters are “speaking truth to power.”

“Every generation has to fight its own battle,’’ he said.

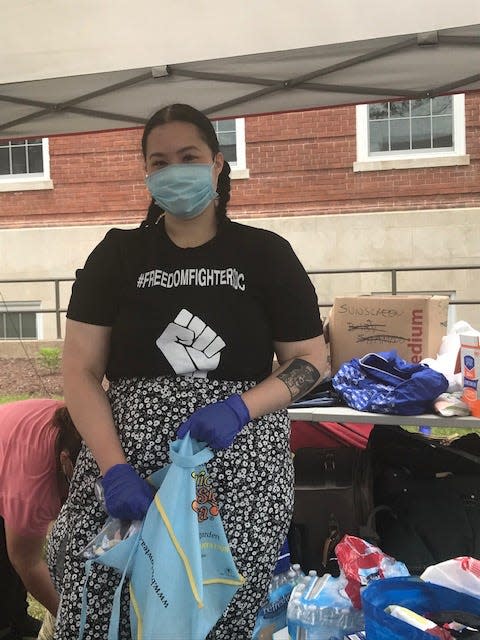

Philomena Wankenge, a founder of the new Freedom Fighters DC, which supports defunding police, said veterans had it “way harder than we do.”

“There were no laws to protect them. There was no, ‘Hey, that is wrong. That’s illegal,’’ said Wankenge, 22. “We’ve got the privilege to have cops literally guide us or mark off roads” for protesters.

Wankenge said it’s because of 1960 civil rights veterans that activists can continue to protest. Earlier this month, her group held a rally near the U.S. Capitol and joined a two-day sit-in across from City Hall.

“We’re still fighting the fight,’’ she said. “But they passed the torch on to us.”

‘I thought we were past that’

Charles Hicks, who started a SNCC chapter at Syracuse University in 1967, called today’s demonstrations a “new birth.’’

“If I was 30 years younger, I’d be out there,’’ said Hicks, a 75-year-old activist in Washington, D.C. “I’m not young enough to run and to dodge tear gas.”

For Father’s Day, he helped organize a “Black Father’s Matter” motorcade across D.C. to salute Black men and remember unarmed Black men who died at the hands of police.

Smith said "there's a hole in my heart'' because he's still having “the talk’’ with his grandchildren, including his 21-year-old grandson who is a senior in college. The conversation includes warnings about what to do if stopped by police.

“I thought we were past that,'' Smith said. "But you want to keep your children alive.”

More: George Floyd. Ahmaud Arbery. Breonna Taylor. What do we tell our children?

More: These 19 black women fought for voting rights

George Floyd video helped inspire latest push for change

Richardson praised today’s protesters for being able to share information quickly, including videos of Floyd’s deadly encounter with a policeman who knelt on his neck for nearly nine minutes.

“When you saw that video, it changed everything,’’ said Richardson, a co-producer of the civil rights documentary "Eyes on the Prize." “That kind of video we did not have. What we did have, though, was understanding that we had to build networks.”

Activists led by Ella Baker, a legendary civil rights organizer, relied on a network of supporters. For example, when activists were arrested, they would call contacts who would then reach out to local officials, including sheriffs, to demand their release.

“We had Friends of SNCC,’’ said Richardson, who kept dimes with her so she could call from a public phone. “That was our version of Facebook and Twitter.’’

Veterans also relied on mimeograph machines, telephones and word of mouth to tell people about events and urge them to attend mass meetings.

Civil rights veterans sometimes waited for news crews to witness the police beatings. That coverage helped garner national support.

Today, protesters turn to Twitter and Instagram to summon people and attract media attention. Freedom Fighters DC, which started in May, has 12,000 Twitter followers and nearly 27,000 on Instagram.

“It motivates people right then and there to do something,” said Hicks, a civil rights veteran of today's response.

1960s protesters were punished for speaking up

For some civil rights veterans, joining the protests meant losing their jobs or getting kicked out of college, even at historically Black colleges and universities. Many were the first in their families to attend college so it was a major decision to join the fight.

Two years ago, state education officials cleared the record of students at Alabama State University who were expelled 58 years earlier for protesting at a segregated lunch counter.

Rickey Hill was arrested and expelled from Southern University in Louisiana in 1972 for helping lead a campus protest over inadequate services and funding. Police shot and killed two unarmed students. Hill said Southern has offered degrees to some students who were expelled. The student union is named after the students who were killed.

Hill, 67, argued there must be structural and systemic changes.

“It’s really frustrating because some of us have faced these guns,’’ said Hill, former chairman of the political science department at Mississippi's Jackson State University. “We have seen people killed. Nothing has been done. So we get this constant sense that the tragedy always turns to farce.”

Richardson, who was at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania when she joined the protest movement, said it was important to have “a constructive vehicle’’ to fight discrimination. For her, that was SNCC.

“I got pissed that they were telling me I couldn’t come through these doors because I was Black…pissed that they thought they could dehumanize me, that they thought they could tell me that I couldn’t vote,’’ she said.

Wankenge of Freedom Fighters DC said younger activists are “more privileged” than veterans of the 1960s civil rights movement.

“They gave up things that we’re never going to have to give up,” she said.

‘Opportunity to tell their truth’

Civil rights era veterans note more diverse crowds are joining the fight against oppression these days, with Americans from different ethnic backgrounds participating in protests, and with Black Lives Matter demonstrations unfolding in London, Paris, Berlin and other cities.

“This movement involves so many more people at a much larger scale,’’ said Hicks, noting demonstrations in states like Utah, where Black residents represent less than 2% of the population. “Everybody is turning out and it doesn’t have to be in a major city.”

While protests may not always lead to substantial changes, people get to make their case, said Hill.

“This is their opportunity to tell their truth, to release their frustration, to make their demands and to say, ‘Look, you’ve got to see us,'” he said. “For the most part, Black people feel invisible in this country.”

Simmons, the young protester from Laurel, said he’s haunted by Floyd’s death and other Black men in police custody. Simmons went to a predominately white high school in Akron, Ohio, where he said he felt like he was a target because of his skin color.

“I’m just scared for my life every time I walk out the front door,” he said.

A day after his graduation in May, Simmons joined his first-ever protest outside a police station in Akron. Simmons, who plans to attend North Carolina A&T State University this fall, has since moved to Maryland and returned twice to downtown D.C., to protest. He said it felt “amazing” to walk on the yellow “Black Lives Matter” letters painted on the street leading to the White House.

“I felt so happy to be a part of something that was bigger than me,” he said.

Follow Deborah Berry on Twitter @dberrygannett

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Civil rights: Black Lives Matter protesters build on 1960s movement