‘We Owe it to Gracie’: A Look Inside This Family’s Quest for Reparations

Candice Hammons’ curiosity about the history of the maternal side of her close-knit family unearthed a mystery along Texas’ Neches River.

It all started with a simple ancestry test in 2018. Her niece had just completed a DNA kit from 23andMe and her excitement was contagious. For Hammons, it wasn’t just about learning where she came from, but who she came from.

With her niece’s encouragement, Hammons purchased an Ancestry DNA kit and shipped it off.

It led the now 51-year-old, who lives in Arizona, to a “shocking” revelation.

Her great-great-great grandfather, Albartis, or Albertis, Arnwine, a slave owner near Jacksonville, Texas, granted his 900-acre estate and freedom to the folks he enslaved in his will. Among them was her great-great-great grandmother, Gracie or Gracy.

But, they never received it.

After Albartis’ death in August 1855, his white family members contested the will all the way to the Texas Supreme Court, which ultimately decided in Gracie’s favor, according to digitized transcripts and court records. However, Richard J. Jowell, one of the executors of the estate, refused to see it through.

Hammons recalled the hurt she felt as she combed through the details of the case. She also went into a state of shock because she thought no one at the time had tried to fight back or get justice. It set in motion her determination to reach out to her family matches on Ancestry to get more information.

Now, the Black descendants of Albartis and Gracie Arnwine are organizing to take back what they say is rightfully theirs. Almost 170 years later, they are in pursuit of compensation and land, which could be used to build proper memorials for their ancestors. Ultimately, their goal is to ensure their family stays together, and their stories are cemented into the fabric of American history.

The land is now underwater due to construction in the 1950s – yet the family is energized.

Whether it’s in Bruce’s Beach, California, Hilton Head, South Carolina, or Sparta, Georgia, Black families’ fights to return lost and stolen land is inspiring, Hammons told Capital B. And it’s urgent that the Arnwine family tell their story, she added. They recently created a GoFundMe campaign to help pay legal expenses and circulated a petition to garner public support.

“Their dignity was taken away. It was a robbery,” she said. “They stole it from them, and the generational wealth passed down, it was lost.”

Uncovering the History

The initial hurt and shock turned into motivation for Hammons. Over the past two years, she’s treated her research like a job, digging into documents and census records, sending emails, and calling relatives almost daily.

Read more: Searching Your Family Tree? Here’s How You Can Find Its Roots.

At first, many folks showed no interest in their history. The more she learned, the more it appealed to new — and old — kinfolk.

Some of those family members are people like Janice Bryant, a family historian and genealogist of over 20 years who provided resources and documents to Hammons. Bryant, who lives in Atlanta, is also the descendant of Winnie or Winney, who is believed to be Gracie’s sister. Bryant shares presentations on this history so that white Americans won’t continue to “sweep our stories under the rug,” she said.

“Stories like our family need to be told because it happened, and despite all these things happening, we’re still here and we’re still rising up and still hopeful for the future,” she added. She also hosts workshops to teach others how to do the same.

It’s also people like Los Angeles resident Mary Tucker, the great-great-great granddaughter of Gracie’s daughter Mahalia Arnwine, who helped compile the research into a book, “Truth and Justice for the Arnwine Family.”

And Texas native Kimberly Crockett, the great-great-granddaughter of Sterlin, or Stearlin, Arnwine, grandson of Gracie, who also joined the research crew and grew the descendant group on Facebook, which includes more than 300 people.

These connections led Hammons and her family to uncover more of the traumatic story.

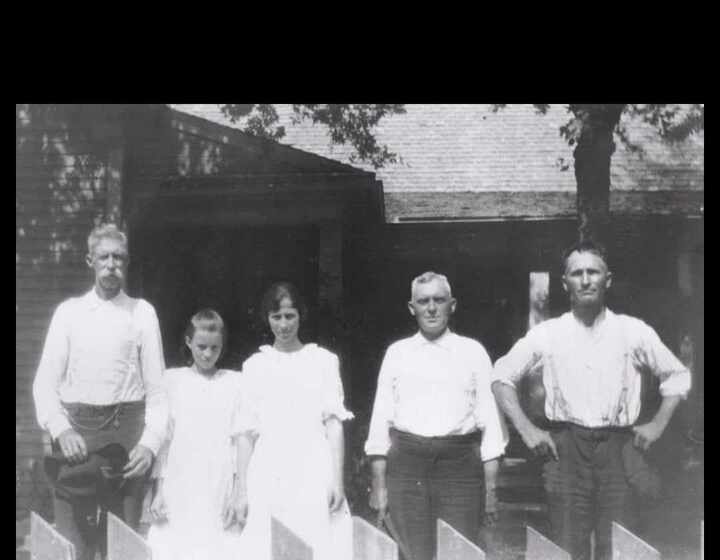

Before moving to Texas from Tennessee in the 1840s, Albartis purchased four women at a plantation in Memphis. They were Gracie, Mary, Winnie, and Anaka, or Ann. Throughout the years, he had several children with Gracie, who lived in the house with Albartis, and Mary. According to the Arwine family, Gracie was Albartis’ common-law wife.

On his deathbed, Albartis instructed that a will be recorded. The will released from slavery the 24 enslaved people, including the women, young girls and one boy, he owned. He also gave them all of his property, including land, stock, and other property valued at $10,000. It stated they shall be his executors and “sent beyond the limits of the state as soon after my death as practicable.”

During the Antebellum era, white slave owners raped and impregnated enslaved Black women. Evidence shows that in other circumstances owners created familial type bonds with enslaved women, yet it was complicated and rooted in violence as the women were not free to make their own choices, historians say.

In some cases, these white men decided to leave money, freedom, and land in a will or pay for the value of their labor, said Noël Voltz, an assistant professor of history at Case Western Reserve University.

One of the hurdles to freedom, though, was the laws that forced Black people of certain ages to leave the state within a certain time. If they didn’t, they faced being enslaved again. If they did leave, they faced the possibility of being split up.

Many states mandated additional requirements to allow enslaved people to be free. Kimberly Welch, an associate professor of history and law at Vanderbilt University, referred to Mississippi in the 1820s. Slave owners had to describe the character of the person and put a notice on the courthouse door and in three newspapers for three months announcing the intention to free each person.

“We owe it to Gracie”

About a month after Albartis’ death, executors Richard R. Jowell and James C. Maples presented a paper writing purported as the last will and testament dated June 1855 and signed by Albartis with an X, or cross mark. The Cherokee County court refused to admit it to the record. The case made its way to the district court in Rusk County, Texas, in December 1858. The court ordered that the will be admitted to the record.

However, Albartis’ two white nephews — Alfred M. Arnwine and Eppenetus G. Armstrong — and William C. Daniel filed a petition against Jowell, the executor, arguing that the will was invalid.

In the suit, they claimed that Albartis’ closeness to Gracie and Mary allowed him to be influenced and “enabled them to extort this pretended will.”

“The negro women Gracy and Mary were by him and around his bed … [and] alternately passed from his bed to the parties who were preparing said will, communicating or pretending to communicate to them the various provisions of the will,” the suit said. “The mind of said Albertis was so enfeebled that he was wholly incapable of understanding or dictating the provisions of the said will.”

They introduced a new will that included various sums of money and acres to several family members and that his “slave hold property,” be given to his brothers Daniel Arnwine and James Arnwine for three years, then grant them their freedom. Additionally, the will would have given them all household and kitchen furniture, money arising from land sales, and cash after debts were paid off.

The case went to the Texas Supreme Court, which ruled in Gracie’s favor. So why didn’t she and others get their freedom or property?

In some cases, if the estate owed debts and the executor couldn’t pay it off, the enslaved people were not freed, Welch said. In other cases, the executor never told the enslaved people that they had been freed in the will.

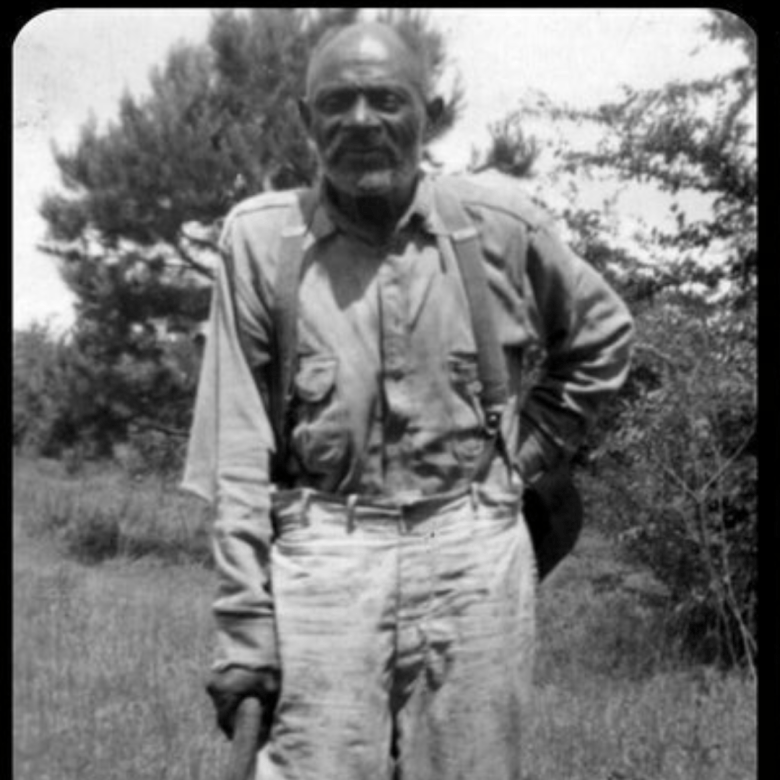

Once the lawsuit ended, Jowell split the family up. He sold many of them and kept others to work for him. Two years later, he sold them, which included Sterlin. In 1937, Sterlin, then 94, spoke about this time during an interview with the Federal Writers’ Project: Slave Narratives project.

“When war broke I fell into the han’s of Massa John Moseley at Rusk. They brought the dogs to roun’ us up from the fiel’s whar we was workin’. I was the only one of my fam’ly to go to Massa John,” Sterlin said.

“Jedge Jowell promised massa [Arnwine] on his deathbed he would take us to de free country, but he didn’. The women never did get that 900 acres of land Massa Arnwine willed to’em. I don’ know who got it, but they didn’. I knows I still has a share in that land, but it takes money to git it in cou’t.”

Anger. Disappointments. Sadness. All emotions felt by the Arnwine descendants when hearing the story.

Crockett’s mouth dropped when she learned about her great-great-great-grandfather Sterlin from her first cousin Byron Bryant, a Texas native, at a family reunion years ago.

“I couldn’t believe it. I knew then we had to do something,” she said. “If it was somebody white and if land was left to them, it would’ve been all over the news.”

Bryant told Capital B he cried like a baby when he learned the story of Sterlin, his great-great-great grandfather.

“I cry when I’m mad. I was really frustrated about what happened and how I couldn’t change anything about it,” Bryant recalled. “What I want is for people to continue to trace their own relatives because you just never know what it confirms. You never know what you’ll find about who you are.”

Even after the revelation, Crockett and Byron didn’t connect with Hammons until last year to join the search for answers. With more family members on board, they are hoping to turn their family’s trauma into triumph. Some of them wish to create a family trust fund to give scholarships to family members pursuing higher education or homeownership. Others desire memorial plaques, T-shirts, and a recreational center where the land is.

Terrie Breedlove, a white descendant of the Arnwine family who lives in Illinois, told Capital B she is supportive of the family’s decision and happy she is getting to know the other side of her family. She’s been in communication with Hammons for nearly two years and helps with research when she can.

“Somehow or another, they should be given ownership, or it should be recognized as a national park or a state park with their names on it,” Breedlove said. “They deserve something. I’ve always felt that way.”

It’s unclear whether the family will be able to get back the land, but Welch and Voltz agreed the family could have a case. Either way, the familial bonds are growing.

In the midst of finding the right lawyer, they are gearing up for their family reunion this summer — a new tradition to keep everyone together, but, most importantly, create a space to keep sharing in order to carry on the legacy. Just recently, the mayors of Memphis and Montgomery, Alabama, sent certificates honoring Sterlin Arnwine in reflection of Black History Month. It’s only the first step, the family says.

“We owe it to Gracie, to our ancestors, to get justice,” Tucker said.

Hammons agreed.

“I have cried because I am amazed at all of this. I’m excited now because I see all of the work, it was worth it,” Hammons said. “The sacrifice that I made to get the book to media coverage to getting the family on board … it’s really coming together, and that’s more powerful.”

The post ‘We Owe it to Gracie’: A Look Inside This Family’s Quest for Reparations appeared first on Capital B News.