How ‘Owning the Libs’ Became the GOP’s Core Belief

For a political party whose membership skews older, it might be surprising that the spirit that most animates Republican politics today is best described with a phrase from the world of video games: “Owning the libs.”

Gamers borrowed the term from the nascent world of 1990s computer hacking, using it to describe their conquered opponents: “owned.” To “own the libs” does not require victory so much as a commitment to infuriating, flummoxing or otherwise distressing liberals with one’s awesomely uncompromising conservatism. And its pop-cultural roots and clipped snarkiness are perfectly aligned with a party that sees pouring fuel on the culture wars’ fire as its best shot at surviving an era of Democratic control.

In just the past month, Sen. Ted Cruz self-consciously joked at the Conservative Political Action Conference about his ill-timed jaunt to Cancun, decried mask-wearing as pro-statist virtue signaling, and closed his speech by screaming “Freedom,” a la William Wallace; House Republican Leader Kevin McCarthy tweeted a video of himself reading a Dr. Seuss book in protest of the supposed censorship of the children’s author (whose estate decided to stop publishing six titles on account of stereotypes in their illustrations); Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene erected a sign outside her congressional office in Washington declaring “There are TWO genders: MALE & FEMALE” across the hallway from the office of Democratic Rep. Marie Newman, whose daughter is transgender; even Rush Limbaugh, the late talk radio giant and progenitor of liberal “ownage,” got in one last braggadocious slap from beyond the grave: the occupation listed on his death certificate is “greatest radio host of all time.”

In one sense, this is the natural outgrowth of the Trump era. Inasmuch as there was a coherent belief that explained his agenda, it was lib-owning — whether that meant hobbling NATO, declining to disavow the QAnon conspiracy theory, floating the prospect of a fifth head on Mount Rushmore (his, naturally), or using federal resources to combat the New York Times’ “1619 Project.”

But in a post-Trump America, to “own the libs” is less an identifiable act or set of policy goals than an ethos, a way of life, even a civic religion.

“‘Owning the libs’ is a way of asserting dignity,” says Helen Andrews, senior editor of The American Conservative. “‘The libs,’ as currently constituted, spend a lot of time denigrating and devaluing the dignity of Middle America and conservatives, so fighting back against that is healthy self-assertion; any self-respecting human being would … Stunts, TikTok videos, they energize people, that’s what they’re intended to do.”

“I can envision a time where [pro-Trump Florida Rep.] Matt Gaetz could pin a picture of [Democratic New York Rep.] Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to his own crotch, and smash it with a ball-peen hammer, and he’ll think it’s a huge success if 100,000 liberals attack him as an idiot,” says Jonah Goldberg, editor-in-chief of the anti-Trump conservative outlet The Dispatch. “It’s a way of taking what the other side criticizes about you and making it into a badge of honor.”

And in a world in which polarization driven by social media has equipped every smartphone-wielding American with a hammer, every political dispute looks like a nail. A year into the Covid-19 pandemic, viral videos of mask burnings and other forms of lockdown protest proliferate. The arch-conservative, troll-friendly webmagazine The Federalist more than doubles its traffic each year. Pro-Trump students are bending reformicon-minded College Republican groups to their will. In certain parts of the country, modified pickup trucks “roll coal,” spewing jet-black exhaust fumes into the air as a middle finger to environmentalists. Popular bootleg Trump campaign merchandise read simply: “Fuck your feelings.”

Randy Rigdon of Cincinnati wears a "TRUMP 2016 - FUCK YOUR FEELINGS" shirt at Trump's rally at the US Bank Arena ==> pic.twitter.com/HFDnuJYdHJ

— Frank Thorp V (@frankthorp) October 14, 2016

“It’s a spirit of rebellion against what people see as liberals who are overly sensitive, or are capable of being triggered, or hypocritical,” says Marshall Kosloff, co-host of the podcast “The Realignment,” which analyzes the shifting allegiances of and rise of populist politics. “It basically offers the party a way of resolving the contradictions within a realigning party, that increasingly is appealing to down-market white voters and certain working-class Black and Hispanic voters, but that also has a pretty plutocratic agenda at the policy level.” In other words: Owning the libs offers bread and circuses for the pro-Trump right while Republicans quietly pursue a traditional program of deregulation and tax cuts at the policy level.

To supercharge those distractions, however, was the great innovation of Donald Trump’s presidency: He used the highest platform in the land to play shock jock 24/7, trading the radio booth for his Twitter account — thrilling his supporters by dismaying his foes. And despite Trump’s defeat in the 2020 presidential election — and the Republican Party’s loss of control of the House and Senate under Trump’s leadership — the GOP has largely chosen to take his strategy and run with it, betting on a hard-charging, antagonistic rhetorical approach to deliver it back into power in Washington.

That’s led to predictable tensions, as the party’s diminishing cadre of wonky reformists lament a form of politics that seems more focused on racking up retweets and YouTube views than achieving policy goals. Even so, Trump-inspired stunt work is, for the moment, the Republican Party’s go-to political tool. “Owning the libs” is no longer the domain of its rowdy, ragged edges, it’s the party line, with the insufficiently combative seen as inherently suspect and outside the 45th president’s trusted circle of “fighters.”

But despite its hypermodern verbiage and social media-assisted dominance, the rhetorical approach deployed by Trump and his allies has roots that go back to the beginning of the conservative movement, with a party, much as it is now, fearful of a liberal status quo it saw as hellbent on making it obsolete.

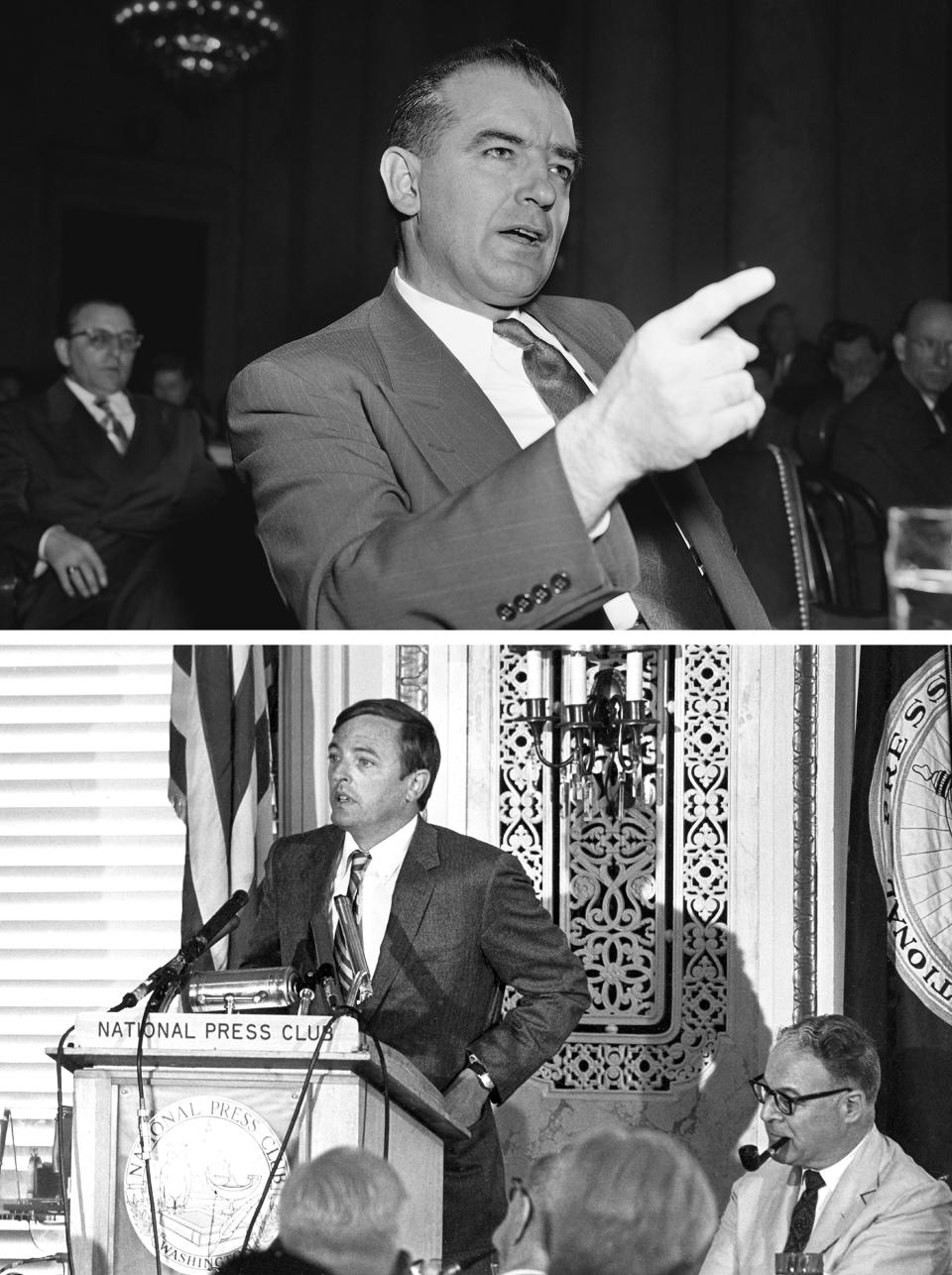

In 1952, the political mainstream was inflamed by the boorishness and recklessness of another conservative demagogue: Wisconsin Sen. Joe McCarthy, then at the height of his infamous communist “witch hunt” within the federal government. McCarthy would eventually overreach to the extent that he was overwhelmingly censured by the Senate, including roughly half of its members from his own party.

One prominent conservative willing to defend McCarthy, much to the chagrin of nearly everybody to the left of the John Birch Society, was Irving Kristol. The godfather of neoconservatism wrote contemporaneously in Commentary that “there is one thing that the American people know about Senator McCarthy: He, like them, is unequivocally anti-Communist. About the spokesman for American liberalism, they feel they know no such thing.”

To Kristol, the certainty McCarthy signaled was worth commending, despite his argument’s lack of substance or his corrosive rhetorical style. McCarthy was a staunch anti-communist, but that was almost secondary to how thoroughly he infuriated his opponents, leaving no question as to where he stood. And given the incentives presented by social media toward ever more extreme political positions, it’s no wonder such stark, if reductive, contrasts are even more appealing today, to the extent that a spiritual heir of McCarthy’s could even win the White House.

“Irving [Kristol] wasn’t a McCarthyite, but the point is a good one,” says Goldberg. “When both sides are encouraged to take evermore extreme positions, I think for the average voter that sort of moves the Overton window a little bit where they say, ‘Look, I think Trump’s a jerk, and I don’t like what he says about immigrants, and blah, blah, blah, but at least he’s not for defunding the police, or at least he likes the American flag.’”

Kristol’s willingness to walk on the wire for such a reviled figure as McCarthy reveals another crucial element of lib-owning, beyond just its galvanizing moral clarity: its place as a tool of redoubt for those in the political and cultural minority. Take, for example, Kristol’s contemporary who perfected the art for the conservative movement’s long, dark years in the post-Goldwater wilderness — William F. Buckley, the National Review founder who relished making his foes look foolish on his long-running program “Firing Line,” and who, when asked why Robert F. Kennedy refused to appear on the program, famously responded with an impeccably troll-ish query of his own: “Why does bologna refuse the grinder?”

“Buckley had his version of ‘owning the libs,’ which was being more erudite and articulate than his interlocutors,” Goldberg says. “You take a certain satisfaction, sort of the ‘your tears are delicious’ kind of satisfaction.”

Buckley’s program lost some of its countercultural punch as the Reagan Revolution took hold in Washington, and almost inevitably, his successor George H.W. Bush’s “kinder, gentler” conservatism created an opening for those who craved redder meat.

Enter, if you will, the John the Baptist to former President Trump’s all-ownage-all-the-time messianic leadership: Rush Limbaugh.

When Limbaugh died in February after a lengthy battle with cancer, his transgressions against liberal good manners, to put it mildly, were widely noted. Limbaugh regularly filled the three daily hours of his program with invective against women, people of color, LGBTQ people and any number of other groups that didn’t include Limbaugh, to the point where even he, the quintessentially self-confident blowhard, occasionally felt the need to admit he’d gone too far and apologize. But to his millions of devoted listeners, no remark was too inflammatory to be brushed aside in light of his peerless talent for owning the libs.

After Limbaugh’s death, libertarian writer Conor Friedersdorf teed off on the late radio host in the pages of The Atlantic, not least as a wanting successor to Buckley: “Limbaugh advanced the smug hatred of liberals and feminists, took pleasure in mocking the left, fueled the ugliest impulses of his audience more often than he sought to elevate national discourse. … He will likely be remembered more for the worst things he said than the best things he said, because unlike Buckley, who said his share of awful things, no Limbaugh quote stands out as especially witty or brilliant.”

Maybe to readers of The Atlantic. On the right, it was far more common to laud Limbaugh, as the “happy warrior” who validated the act of sticking one’s thumb in the liberals’ eye to a cadre of once-timid Chamber of Commerce rats.

“Liberals who didn’t listen to Rush, and just read the Media Matters accounts, never understood how *funny* he was,” National Review editor-in-chief Rich Lowry—himself a Buckley protégé (and POLITICO Magazine contributing editor)—wrote on Twitter. “What set him off from his many imitators was how wildly entertaining he was, and the absolutely unbreakable bond he formed with his listeners.”

Goldberg—who, by his own account, is no fan of Limbaugh—noted that despite the radio host’s self-confident bluster, his appeal was ultimately in providing a form of aggro-catharsis for listeners who felt embattled by the media’s pre-internet status quo.

“There really was a much more monolithic mainstream media, and what Limbaugh was doing back then was sort of giving equal time, as it were, to the other perspective,” Goldberg says. “As the country’s become more polarized, and we reward the outrageous beyond its worst, you get this race-to-the-bottom competitiveness, where people want to get noticed and have to be even more outrageous than the next person.”

And where, of course, for things to get more outrageous than social media?

“My entire life right now is about owning the libs.”

Thus the zeitgeist was spoke into existence in 2018 by Dan Bongino, on the National Rifle Association's now-defunct web video channel. Bongino — a successful right-wing podcast host, who was tapped this week by radio giant Westwood One to fill Limbaugh’s now-vacant airtime in some markets — was ostensibly incensed by the treatment of Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh during his Senate confirmation hearings. But the subject of his outrage was hardly a material issue.

Take the man at his word: Bongino’s preoccupation, then and now, is owning the libs more than securing any kind of policy outcome or vote in the Senate. He’s continued to do so even despite quitting Twitter in protest after his account was restricted amid the January 6 riot; his content is consistently among the most shared on all of Facebook.

But in October 2018, Bongino’s declaration was revealing. Until then, the phrase “owning the libs” was mostly deployed by those seeking to mock conservatives for quixotically pursuing cheap applause from their base at the expense of a true political win (or, simply, their dignity). The phrase is barely apparent in the public record before 2015, when its usage on Twitter began to slowly ramp up; the “Own The Libs Bot,” a popular account which affixes the phrase “own the libs” as a non-sequitur to various random clauses, seemingly to highlight the perceived absurdity and desperation of Bongino-like figures, wasn’t even launched until November 2017. Perhaps the best example of this original, ironic deployment of the phrase just a month earlier described one particularly ill-conceived stunt by a campus Republican group: “owning the libs by wearing diapers in public.”

In those early days, even some name-brand Republicans got in on the fun, albeit with more of the tone of a concerned parent. Then-United Nations Ambassador Nikki Haley made headlines when in the summer of 2018 she addressed a group of high schoolers attending a youth leadership summit at George Washington University. “Raise your hand if you’ve ever posted anything online to quote-unquote ‘own the libs,’” Haley requested, leading many students to do so and burst into applause.

With the patience of a Nancy Reagan “just say no” speech, the ambassador admonished them that owning the libs is “fun and that it can feel good, but step back and think about what you’re accomplishing when you do this — are you persuading anyone? Who are you persuading? … We’ve all been guilty of it at some point or another, but this kind of speech isn’t leadership — it’s the exact opposite.”

Unfortunately for Haley, a fairly prominent figure in the conservative world happened to disagree: her boss, the president of the United States. And while Haley has had her own very public reckoning with the tension between her ideal of leadership and Trump’s, it’s clear which has won out in the Republican Party.

Conservative social media is dominated by controversy-chasing attack dogs like Bongino. Donald Trump Jr. — a social media star in his own right who titled his first book simply “Triggered” — is considered a formidable candidate for the 2024 Republican presidential nomination should he choose to run, based on little more than his dynastic pedigree and talent for lib-owning. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, who’s embraced Trump’s thirst for conflict more than maybe any other viable Republican presidential candidate, handily topped the 2021 CPAC straw poll of ’24 contenders — the one, of course, that didn’t include Trump himself.

Despite both the invited scorn of liberals and the quieter resentment of conservatives who worry their policy dreams might be tanked by a movement that turns off the moderate suburbanites who elected President Joe Biden, “owning the libs” is at the center of today’s Republican Party because, well, it works. Behind Bongino’s astronomical Facebook engagement numbers are millions of real people, ready to show up at voting booths in GOP primaries. In 2020, after four years of nonstop ownage, more people voted for Trump than any other presidential candidate in history — save for, of course, Joe Biden.

“I can’t even count the number of times that people on the realignment side of conservatism, populist-minded conservatives, have said to me, ‘If only we had a candidate who believed all the right things and didn’t have Trump’s baggage,’” says Andrews, senior editor at The American Conservative. “I think that point of view is idiotic. Trump’s attitude had a lot to do with his success. You can’t have unapologetic populism without Trump’s personality. … ‘Owning the libs’ is something you do when you feel insecure in your social position, and Trump is the opposite of that. He’s confident, he owned the libs like a winner, and that’s what made him so special.”

Still, even many conservatives are skeptical that Trump’s particular genius at infuriating liberals and thereby rallying new voters to his side is transferable to an heir. He might be one of one: the arch-conservative Sen. Tom Cotton notably stumbled in his own Trump-like attempt to whip up the base at this year’s CPAC, and his peers did little better, a few notable exceptions aside. Sen. Josh Hawley has a unique talent for infuriating liberals through his support of Trump’s conspiracy-mongering around voter fraud, but he’s a famously uncharismatic speaker. And, by now, Ted Cruz’s act is quite simply stale, lacking any real capacity for transgression.

“Ron DeSantis was incredibly aggressive towards the media, and a lot of people on the right that I know cite him as an example of someone knowing how to play to the base,” says Kosloff, co-host of the "The Realignment" podcast. “But how much is ‘own the libs’ just then a commodity product which all GOP politicians are expected to produce? Unless there are large levels of Trumpian ability, I doubt it’s going to be a breakout feature.”

Trump occupied a sui generis place in popular culture—he wasn’t just a lib-owner par excellence, but was seen as a businessman-outsider in the mold of Ross Perot; one of the first reality television stars; a cultural fixture referenced by everybody from Robert Zemeckis to Redman. “Owning the libs” might be a necessary condition for those who would seek to claim his mantle, but it alone is insufficient for general election success.

Even so, it’s difficult to imagine any serious Republican presidential contender, at least in the near future, winning a primary with a conciliatory platform akin to Jeb Bush or John Kasich’s from 2016. Trump has repeatedly professed his desire for a party of “fighters”—that is to say, inveterate lib-owners—and the fact that he’s still the most popular Republican politician of the past decade ensures he’ll have his way. It may be on a foundation laid by McCarthy, Buckley, Limbaugh and their followers, but today’s ownage-obsessed Republican Party is ultimately the house that Trump built.