Oxtail’s centurieslong roots in Black communities is a history worth protecting

At the beginning of the year, a tweet — or rather, the responses to a tweet — brought to the forefront a food-related phenomenon that, up until that point, had been flying under the radar.

On Jan. 7, Insider Food shared an original video that was produced back in 2019 on its Twitter. The video was about oxtail, a slow-braised, stewed dish made using the tail of either beef or veal cattle, and hosts in the video enjoyed the delicacy at a New York City food truck called Island Spice Grill.

Oxtail is a dish that is popular around the world, but specifically within the Caribbean and within Caribbean communities in the US pic.twitter.com/fB96aZtQWs

— Insider Food (@insiderfood) January 7, 2023

The cut of meat, which is prepared in many cuisines around the world, including Italian and Chinese, but is a staple in Caribbean and soul food cuisines, has edged its way into the culinary conversation at large.

Insider's video has garnered 12.7 million views and thousands of retweets, but what's most notable is a peculiar phenomenon that unfolded in the tweet's replies.

One time, I had oxtail, and it gave me hair loss and my credit score went down. I wouldn't suggest eating oxtail at all. Avoid it.

— Fat Kid Deals (@FatKidDeals) January 8, 2023

"One time, I had oxtail, and it gave me hair loss and my credit score went down. I wouldn’t suggest eating oxtail at all. Avoid it," tweeted one person.

"Oxtail is disgusting. Causes all kinds of gastrointestinal issues. Had to go to the ER once after having some once, wasn’t worth the bills afterward smh," tweeted another.

“If you have naturally straight hair oxtail (particularly the oils) can cause hair loss,” warned another Twitter user. “It is striking.”

A flurry of shocked responses wondered if it were true: Could oxtail really make your hair fall out? This included one man with a bald spot refusing to risk taking a tender bite of oxtail even if others were being facetious. That is, until one user decided to tell it like it is:

“They’re trying to prevent the whites from gentrifying it and making it expensive as hell,” they tweeted, revealing what all these tweets were actually about. No hair loss, throat closures or impotence follow a serving of oxtail, only a deeply flavorful and uniquely tender culinary experience — one that is instinctively worth protecting to the communities of color that have grown up with it.

Sweet and Spicy Oxtail with Cassava Dumplings by Nyanyika Banda

As the original tweet from Insider said, “Oxtail is a dish that is popular around the world, but specifically within the Caribbean and within Caribbean communities in the US.”

As oxtail finds its way into the national lexicon and fine-dining establishments across the country, it also faces culinary gentrification. Once an inexpensive item, oxtail is currently in the process of joining previously niche ethnic food items like hummus, ramen and more in becoming mainstream — and more expensive —in the U.S.

Is that a bad thing? Well, it's complicated.

Oxtail’s journey from the scrap pile to the top of the heap

Though oxtail used to only specifically be the tail of an ox, today, it can be the tail of any beef cattle or veal. Oxtail is a class of meat product called offal, or the pieces of the animal that are left after butchering.

Usually, offal refers to the internal organs of an animal like the heart, the hoof (referred to as "trotters" in the meat section) and the stomach, but oxtail, consisting of tailbone, collagen-rich marrow and some meat, is put under this category as well. At the beginning of the American slave trade, when soul food originated, while the prime cuts of meat were reserved for slavers, offal — like oxtails — was what enslaved people were mostly given to eat.

“Whole-animal cooking was what food was about for centuries, and people didn’t waste,” Adrian Miller, culinary historian and author of “Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine, One Plate at a Time,” tells TODAY.com. “A hallmark of soul food and African heritage food in the Americas has been the use of these cast off parts: ham hocks, ox tails, pig ears and all these extremities because the culture was about using all parts of the animal.”

Miller says that only higher class people like slavers could decide whether to eat certain parts of an animal, and prestige meats like prime rib and mutton had value. “Enslaved people did not get regular access,” he explains.

Deprived of most native African vegetables and fruits that they were familiar with, enslaved people eventually learned to cook with what was grown on the plantation and plants and animals indigenous to the regions where they lived — save for items like okra, black-eyed peas and watermelon, which were transported during the Middle Passage.

“When it comes to African American food and our culture, people think it’s just about pork, but that’s just really not the case,” Miller says, adding that since a lot of early food history — especially pertaining to the details surrounding the enslaved — are just not documented. Frederick Douglass didn’t even know his own birth date, a particularly telling example of what details about enslaved people were deemed necessary to know.

Over time, the enslaved melded West African and Southeastern Native American styles of cooking, using on-hand ingredients like yams, onions, cabbage and collard, mustard and turnip greens.

During this, the birth of soul food, enslaved culinary mavericks made use of ingredients like potlikker (the flavorful broth left behind from boiling beans and greens) to slowly braise oxtail until the delicate and flavorful meat fell to delicious pieces.

With rice, black-eyed peas and greens, these components make up a typical Southern oxtail, a dish that has thrived over multiple centuries, making its journey from literal antiquity to a lauded soul-food staple today.

The cost of oxtail going mainstream

With interest comes growing prices, which some attribute to the cut of meat becoming more mainstream.

According to Google Trends, the public’s interest in oxtail has been steadily rising, with high peaks appearing in 2021 and the beginning of 2023, as folks previously unfamiliar with it find out how truly wonderful it is — if it’s made right, of course.

“Over time, what we’ve found is that oxtail, like most of these provisions which were once relegated to the poor and social lessers became part of a new cultural awareness,” Brigid Washington, journalist, educator and author of “Caribbean Flavors for Every Season,” tells TODAY.com.

Washington says that historical subsistence foods like oxtail, saltfish and callaloo were once considered poor man’s food, and over time gained prestige and financial value. “They held a certain social richness in that it was a path forward, a map towards what our ancestors ate,” she explains.

According to the USDA’s National Monthly Grass Fed Beef Report, beef oxtail has risen in price from a little over $9 in January 2018 to nearly $14 per pound. Most oxtail recipes involve about 4 to 5 pounds of oxtail — take Al Roker’s recipe for his mother’s oxtail and dumplings, for instance — so the everyday oxtail lover, like Al, is looking at significantly higher costs when making the staple dishes they’ve grown up with.

Oxtail Stew and Dumplings by Al Roker

“I think that it’s always important to frame it as a narrative: Oxtails are usually served with rice, peas and sauteed cabbage in the Caribbean; those are inexpressibly an oxtail meal,” Washington says. “I think if you’re just looking at the price of oxtails, you have to also recognize that oxtail is served with these three other very accessible, cheap ingredients. When you look at the whole plate, it gives you context.”

Washington also notes that the rise in demand and price of oxtail is only happening in the States. "If I go home right now and talk to one of my aunts she will scoff, because she will still be able to get oxtail cheap in Trinidad. That's just a fact," she says.

A double-edged butcher knife

In response to the current oxtail prices they're facing at the butcher, people on Twitter, TikTok and beyond are turning to humor to cope — and potentially scare people off from buying it. Washington believes this defensive instinct is a natural one.

“When something is when you see something threatened by a majority culture, you protect it, you insulate it,” Washington says. “It’s what happens with any type of any type of vulnerable commodity.”

But while no one celebrates the rising cost of a favorite food, there is a silver lining to this pricy storm cloud.

“I have mixed feelings about it all, because I want African heritage cuisines to be celebrated,” Miller says. “The only way that they’re really going to be celebrated and ultimately accepted is if people feel comfortable going to restaurants or people’s homes and eating those foods, then making that on their own.”

Miller points to the story of Chinese, Italian and Mexican food in our country as examples. The only way to combat racism in food culture, he says, is to show how wonderful every cuisine is — including soul food.

“I understand that if these things go mainstream, it’s going to mean an increase in price and a lack of availability,” Miller says.

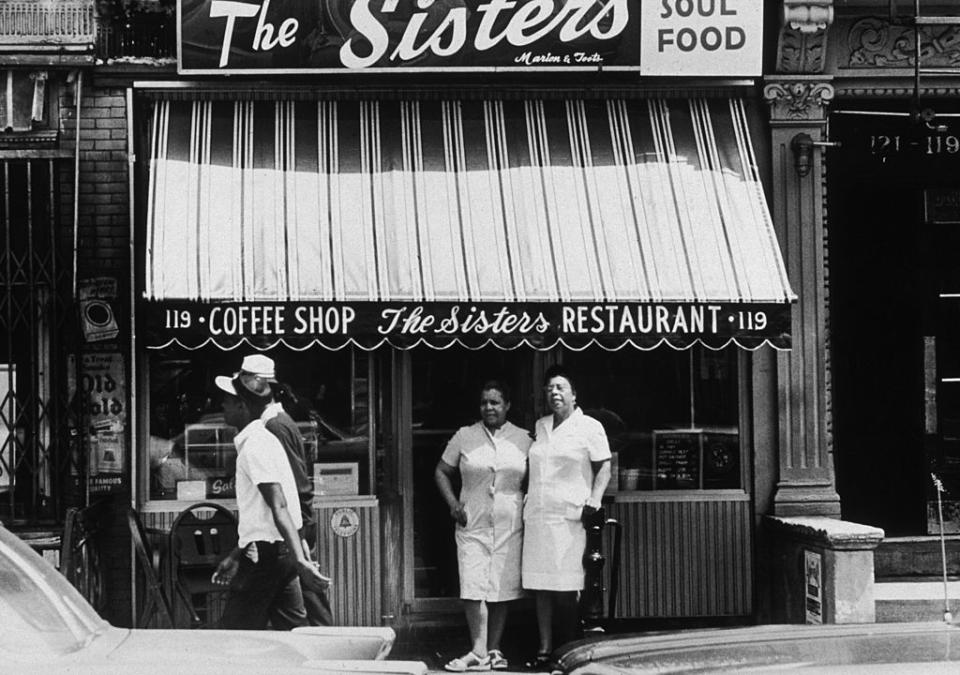

“There seems to be a faddish quality to it — in the 1960s, the same thing happened,” he adds, bringing attention to the soul-food boom of the 1960s which first began with Amiri Baraka’s coining of the term in a seminal essay. “But then five years later, it wasn’t a problem.”

Although oxtail may make our wallets a little lighter for the time being, attention on them and the dishes that make soul food and Caribbean cuisine so special cannot be discounted.

“I want soul food and Caribbean food to be more widely beloved,” Miller says. “And the only way that’s going to happen is if they go mainstream.”

This article was originally published on TODAY.com