Get paid for your data? California governor wants tech companies to show you the money

SAN FRANCISCO – During his State of the State address last month, California Gov. Gavin Newsom made a brief, if bold, promise.

“California’s consumers should be able to share in the wealth that is created from their data,” said Newsom, who went on to add that his team was working up a proposal for what he called a "data dividend."

The term was simple, self-explanatory and puzzling.

A law that would compensate consumers for the use of their data by tech monoliths such as Google and Facebook, who make billions off this information, is so novel it would be a national and indeed global first.

But as appealing as a data dividend might sound, data privacy experts say it is far more easily announced than implemented.

Supporters of a data dividend say it is a natural extension of California’s precedent-setting consumer Consumer Privacy Act of 2018, which goes into effect in 2020 and grants residents the right to know what kind of data is being collected, what it’s being used for and whether it should be deleted.

But unlike the Alaska Permanent Fund, which in the '80s started doling out $1,000-and-up checks to state residents who were sharing in the state's easily tallied oil wealth, a California data dividend would have to apply a concrete value to largely intangible and often anonymized digital information.

There's also concern that such a dividend would establish a pay-for-privacy construct that would be biased against the poor, or spawn a tech-tax to cover the dividend that might push some tech companies out of the state.

“Taken as a whole, this could be good, but if this allows companies to tell consumers we’ll give you a rebate if you don’t insist on your privacy, we’re opposed to it,” says Adam Schwartz, senior lawyer with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit that defends digital privacy and free speech.

More: Who's misusing your personal data? Why we need federal privacy protection regulations.

More: How to stop your smartphone from tracking your every move, sharing data and sending ads

State Assemblyman Jordan Cunningham, a Republican who represents the Santa Barbara area, says his constituents are deeply concerned about the security of their online data, but it remains to be seen if a dividend would be universally embraced.

“What’s the risk in lost jobs and tax revenue if a company leaves? And is this a class action suit for 47 cents a person, or save-for-college money?” Cunningham says. “It’s all intriguing, but the devil’s in the details.”

Google, Facebook and Apple did not respond to a request for comment about the governor’s data dividend plan.

Representatives of Newsom’s office also did not respond. But early indicators suggest the notion already has struck a chord.

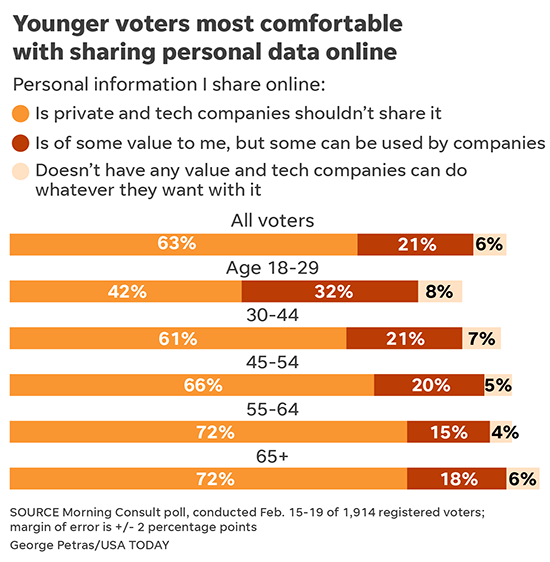

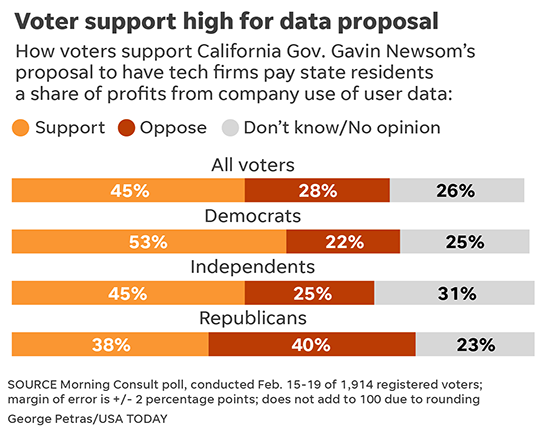

A Morning Consult/Politico poll of nearly 2,000 registered voters conducted Feb. 15-19 revealed that 45 percent supported a dividend payment, while 28 percent said they opposed it.

Why would someone not want to get a check in exchange for data?

The answer could lie in another of the poll’s responses: 27 percent said they didn’t place much or any value on their data, while 10 percent said responded “Don’t Know/No opinion.” If a data dividend were to suddenly cause some tech companies to charge for their free services, some users will be upset.

To that point, last year researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology released a study that said consumers would have to be paid $3,650 to give up online maps for year, $8,400 to give up email and $17,500 to give up search engines.

'You can think of it as a co-op'

Jim Steyer, CEO of tech and media advocacy group Common Sense Media, which is poised to release the details of its data dividend bill later this month, bats away such criticism as premature.

“There’s no target to shoot at,” he says. “A data dividend is complicated, and we’re taking the time to do it right.”

Princeton University economist Glen Weyl is among the experts working on the Common Sense Media bill, which will be reviewed by Newsom and other tech-centric California lawmakers.

Weyl would not disclose the specifics of the plan, but offered three avenues for implementation: an extreme tax on the total profits of a tech platform given out pro rata to consumers; a dispensation of funds based on the value of each individual’s data; or groups of consumers forming a “data labor union” to mediate for a portion of profits.

“I only see the third option as actionable,” says Weyl, who adds that the main point of the bill is to “raise awareness of this issue and get these data union-type groups to form, because as AI (artificial intelligence) grows so could the value of this type of personal information.”

However a data dividend plan were to be structured, most industry experts say such payments would not be life-changing, at least in the short run.

Consumers might receive from hundreds to perhaps a few thousand dollars a year, says Shane Green, CEO of Digi.me, a British-based platform that hosts apps related to data privacy.

“Facebook makes maybe $50 a year per user, Google around $120,” says Green. “But the bigger use of data could be in much more specialized areas, where the value could increase.”

He says market research companies and medical groups looking for very targeted data are in a position to pay more.

Next month, Green’s platform will begin hosting UBDI, which stands for Universal Basic Data Income. Users who agree to release their aggregated and anonymized data to representatives from the $50 billion market research world get paid in a digital currency; the more people sign up, the more valuable the information becomes to companies and the more digital currency is split.

“We’re trying to build a way for everyone to participate in the economics of their data,” Green says.

Dawn Barry is taking a slightly different approach to compensating users for their data. As president and co-founder of LunaPBC, a data management company, Barry has soft-launched LunaDNA, which pays anyone who shares DNA information with researchers by giving them shares in her company.

“You can think of it as a co-op,” says Barry. “We’re not talking about life changing money, and most of the people we talked to said it’s less about the money and more just an expression of fairness.”

Barry is skeptical tech companies would react well to state officials taxing them in order to be able to distribute checks to a large percentage of the state’s 40 million residents.

“If Facebook were to give you a cut of their revenue, I’m not sure that jibes with their business model,” she says. “Philosophically, I agree with a dividend. Operationally is another story.”

'The stuff CIO nightmares are made of'

The existence of Newsom’s data dividend proposal can be attributed back to Europe’s 2016 adoption of its ground-breaking General Data Protection Regulation, or GDPR.

European regulators have been far more aggressive over the years in going after largely U.S. tech companies for everything from data breaches to disseminating individual usage information without informing consumers.

In January, the GDPR showed its teeth when EU regulators fined Google $57 million for not properly disclosing to users how it was collecting data to create targeted ads.

Here in the U.S., a rash of data privacy breaches – foremost perhaps the Cambridge Analytica data breach affecting 87 million Facebook users that may have influenced the last presidential election – has given momentum to lawmakers looking to impose more restrictions, if not outright regulations, on tech companies.

While privacy advocates hail California’s implementation of similar rules, industry experts at times question whether it might not create a set of rules that could not be implemented across all 50 states.

“As people move from one state to another, presumably the rules regulating their data would also change,” Danny Allan, vice president of product strategy at data management company Veeam, wrote in a Fortune opinion piece. “How can organizations possibly keep track. This is the stuff CIO nightmares are made of.”

But some California lawmakers are not interested in waiting around for Congress to pass a comprehensive GDPR for the U.S.

“Having served in Congress for 24 years, I can tell you that Congress looks to serve as the floor and not the ceiling in terms of protecting Americans and our interests,” says California Attorney General Xavier Becerra.

Becerra has spearheaded a number of lawsuits against the Trump administration that have helped mark the state – which boasts the world’s fifth largest economy, largely hinged on tech – as a pioneering maverick.

“As long as Congress helps boost privacy rights, that’s good,” he says. “We want the Feds to do no harm, and not get in the way.”

As for the governor’s data dividend proposal, Becerra says “how it gets done, where and when, those are things to be fleshed out, but the bottom line is that if your data is used for profit then you shouldn’t be left out.”

For Common Sense Media’s Steyer, the enactment of a mandated dividend for California tech users is about acknowledging that tech companies long ago ceased being quixotic little ventures launched by kids in garages.

Larry Page and Sergey Brin, Mark Zuckerberg, and Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak might have started short of cash and long on dreams, but today, thanks in large part to huge adoption rates and few barriers, the market capitalization of Alphabet, Facebook and Apple is more than $2 trillion.

“This is the next frontier in the privacy debate, and we have a governor who is very interested in being a leader on technology and social justice issues,” Steyer says.

Steyer adds that while no “substantive conversations” have yet to happen with tech companies on the topic of dividend, he feels confident that it is not a monolithic block that will respond in lockstep.

So what about those digital-data paychecks popping into user mailboxes in exchange for bits and bytes of your life, is that truly a possibility?

“The answer,” he says, “is stay tuned.”

Follow USA TODAY national correspondent @marcodellacava

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Get paid for your data? California governor wants tech companies to show you the money