The Painstaking Process Behind LEGO's Most Popular Car Sets

Chris Stamp is the design manager for LEGO's Speed Champions series, cars that have to look and feel like the real thing, even though they're made out of about 300 bricks. Stamp sat down with us for a story in the Handmade Issue of the magazine, but the full interview held so much more than we could fit in print, so please enjoy this behind-the-scenes look into the world of LEGO cars.

The below interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Road & Track: When you start a new set, how does the process work? What is the first thing you look at, and then how does it progress to become the finished deal?

Chris Stamp: So normally, the way it works is we don't get given assignments. LEGO, being a huge company, we kind of work as independent small projects. Small companies, basically. On Speed Champions, what happens is I map out the strategy for several years, and then I look at, "Okay, I would like to get X number of products." But we probably won't get that so I make strategies and backup plans.

Then I work on what are the right vehicles. Basically, what I do is put together an assortment looking at new vehicles. I have a lot of close contacts in the automotive industry that I've been able to build up over the years. I think to date, we've worked with 22 different partners.

I'm already aware of vehicles coming out in 2025, '26; even though right now they might just be a clay model in a factory or a design studio, we've built such strong connections that they're very open with us and we're very open with them. And we like to think long term.

I look at all partners like that because one of the things I've tried to push as well is that I don't want to pick favorites. I want to treat Ferrari the exact same way I want to treat Porsche and the exact same way I treat Pagani. Because I've been in so many meetings over the years where you'll talk to one automotive partner and you'll say, "Oh, I really want to work on this product." And they'll turn around and say, "Okay, how many is this other company getting?" So I tried to cut all that out and say, "Look, I know it's a competitive automotive industry. We don't want that. We want to treat everybody equally. We want to give everybody one product. We want to give everybody the best vehicle that we can."

At the same time, I've been trying to push, the last few years, how do you get novelty into just a collection of cars? Because a lot of people will look at it as just a LEGO car, and they won't look at the brand or the build or the IP or the proportions or the accuracy, and all those things. Because we are also talking about kids who are maybe a little bit less of a petrolhead. That's why I was pushing novelty through IP partners.

But then also looking into new types of vehicles, which allows us to appeal to casuals from a visual perspective. So if you do a LMP car or a Can-Am, the silhouette is very different compared to just doing another supercar or hypercar. So I try to look for those little tricks where, "Okay. A casual might not know the brand, but what are they going to be paying attention to?"

Basically, all these different ingredients go into my outline for the strategy of which is the right vehicle to pick at the time. Then we get into the vehicles themselves. I'm very privileged in my role that I see a lot of cool cars and I get to see them up close, full-scale, and all that kind of stuff. But that's only half of it because it would be very easy for us to say, "Yep, I like the car. Let's do it. We'll just build it. It doesn't matter how it looks. We'll just put some stickers on it and put a Ferrari logo on it. And it's a pile of red bricks with a Ferrari logo." We don't want to do that. With Speed Champions, our goal, and I think we've seen this a lot with our consumer feedback in the last few launches is that accuracy is our focus.

It's never going to be a die-cast. It's still going to be LEGO, but the more accurate we can make that, so that if you do remove the stickers, you can still tell which vehicle it is or which vehicle it's trying to represent. So that's something that we've really tried, we would never accept a vehicle that we couldn't do justice. That's one of the things I spend a lot of time talking with different companies about: "I love this vehicle but we can't do it justice. So I'd rather that we maybe save it till next year when maybe we can create some new components to make it possible." Or it could just not fall in the assortment. I would like a variety of different types of vehicles, Can-Am, LMP, Top Fuel Dragster, Formula 1.

I wouldn't necessarily want two F1 cars at the same time from two IP partners, because for us, the build experience, the fact that it isn't a die-cast is also crucial, and I wouldn't want to sell you guys the same thing twice and the only difference is the color and the IP stickers. The build experience for us is crucial.

When all of that is said and done, we do have the standard internal loops where you propose it to the bosses and say, "Do you trust what we're saying right now?" Most of the time, because the bosses aren't petrolheads, they haven't gone into the amount of research and detail that we have. They trust us. They know that we've done the leg work.

Then I can brief the team of designers and say, "Okay, this is the vehicle I want you to work on. These are the key details on this vehicle that you have to capture." I'm in a very lucky position because I also get to design as well as lead the team. I always take one or two of the vehicles. That allows me to keep up to date if we make new pieces or new building techniques, so I can kind of lead through example.

And then together, I've got basically a very open policy in our team. Some projects have a kind of, "This is your model to work on." So you take ownership, and you run with it. On our team, I don't do that. I said the complete opposite. I said, "This isn't your model. This is our model. Just like the model I'm working on isn't mine. It's our model. So you feel free to come to me with any criticisms you have about the work I'm doing. And I want to know. Because I want to make this the best I can. And the only way I can make this the best is if I put all of my ideas into it and you put all of your ideas into it, and we really try to approach it as a design team rather than individuals."

That's got pros and cons because, being designers, we are very emotional and we do get connected to our babies. However, because we've got a returning team every year, we've been able to get used to that mindset and remove the self-attachment to a certain extent, which is great. We can all work in parallel to the same goals. It probably sounds detailed, but it's a very simplified version of our process.

R&T: It's great that you take the ego out of it. It's everybody thinking together.

CS: I've been on the team since it started back in 2015. And when it started, I was just the designer. I had a lead, and then I did all of the products for the project. And then after a while, I went off. I did a couple of other projects. I came back, and I was in charge of the team. When I came back in charge of the team, we went from being six-wide, what we call six modules-wide in LEGO. So that's every time you've got a little LEGO circle on the top of a piece. We call that one module. We used to be six-wide, but the proportions were not correct. The proportions were completely off. The cars looked very skinny and long.

If we just focus on accuracy and correct the proportions, you're going to see a lot more positive feedback from the consumer because the consumers are so passionate about this area -- not just kids, but dads who were kids once. They had posters on their bedroom walls when they were teenagers. Everybody finds vehicles appealing at least at one stage of their lives. Putting accuracy at the beginning, that was my goal. And around that, I added, being OCD, I put 50 strategies together. So strategies about the way we present our sticker sheets because we always have a lot of stickers. And one of the strategies that I had, an unwritten rule in the team was, "Leave your ego at the door."

It doesn't matter if I am the biggest fan of Mercedes in the world or if I hate Mercedes. If Mercedes is the right vehicle to have in the assortment, it's going to be in the assortment. It's been a bit of a challenge to get people internally to understand that. Because everybody's always so passionate that they put their own opinions may be as saying it's a fact. So that's something that we've tried to push out.

I do what we call a petrolhead huddle every year where I get a lot of the petrolheads from our design organization. There's 300 guys. I take 10 petrolheads, and I get them to make a list of what vehicles they like and what's cool. And if they've heard any rumors and stuff. Every single one always writes the car they're driving. Even though we are in Denmark, so cars are super expensive here so they're always not the best cars, they always write, "Let's do my car." So yeah, I tried to get the guys to leave that. Let's call that plan B.

R&T: So, a lot of people asking to make a Nissan Micra?

CS: Yeah. Exactly. It's funny.

R&T: When a set is commissioned, what's the trial and error process? How many different iterations of that model do you go through?

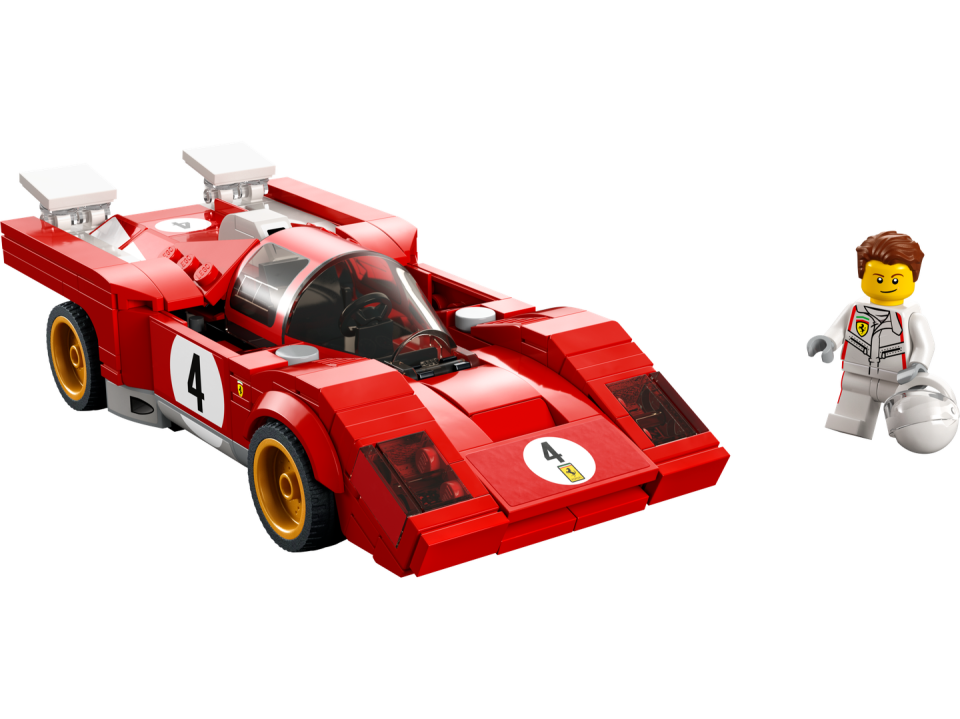

CS: We do a few more loops than most projects. Like me and my right-hand man, Søren [Dyrhøj], we've been doing this together for about five years, and the best way to describe us is that we are just two stubborn grumpy guys. It's because we're so passionate about it, that we're really anal about the details. LEGO has the saying that “The best isn't good enough." We day in and day out believe that, which is a pain in the butt when you're trying to do something in an Excel spreadsheet timeline. But we definitely live by that. For example, when I did the Ferrari 512 M, I think there were about 64 versions.

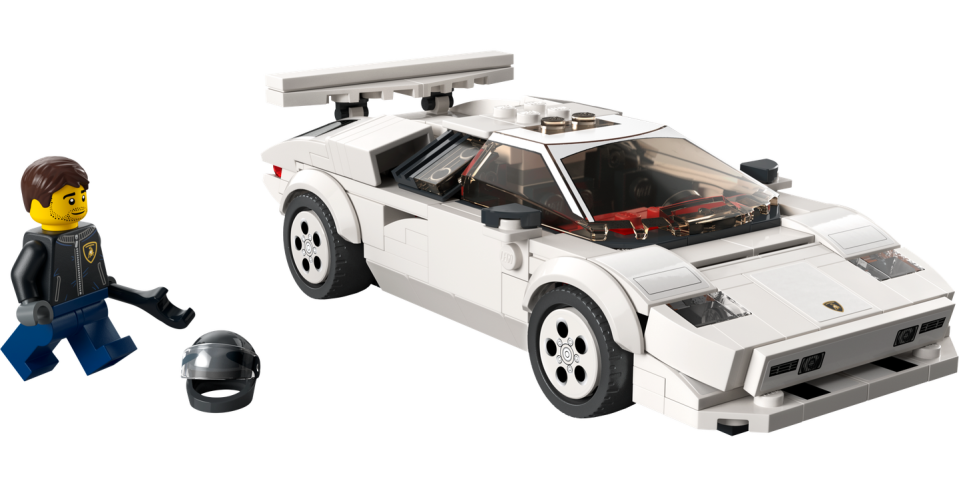

A lot of models go through multiple iterations, but we might have 20 versions just for how we build the front, and then 20 versions for how you build the back. And then, can they combine? Do they not combine? How does the transitions work? Fortunately, we work digitally as well as physically. And sometimes it's quicker to explore iterations digitally because most of that's copy-paste and a little bit of tweaking. But we do loads, and I've got a cupboard in the design area. There's 50 versions of a Countach, for example.

The first ones are very, very crude because we always need to get that first one built. And then, that just gets the ball rolling. The first one's never great. The first one's just kind of, "Okay, what are the proportions? Does it look right?" Just to get you connected with the vehicle because we don't know every vehicle. I mean there's some that we are super passionate about. Countach, we were super passionate about. We tried to do that for a few years and we could never get it right. The Mercedes Project ONE, that's a car that we tried to do for three years. And then Mercedes kept postponing, which was a benefit because it gave us more time to explore. But we end up with so many iterations. Other vehicles, we might do 15 iterations and that might be all it needs.

It also comes down to the designers. Some can say, "Okay, that's good enough. Nobody's going to notice if that little detail is not right." I know that, for example, me and my right-hand man on the team, we never say, "That's good enough." We normally time-out in the process rather than give up with a week to go. So there's not a right or wrong way to do it. Everybody's got their own process.

R&T: Let's say you're building the Countach, and you see that it would really benefit from a certain curved small piece. If it doesn't exist, is there a process to create the piece? Do you mock something up and then commission it, and then, that delays the project a year?

CS: Every year we make new pieces. Speed Champions is one of the projects with the least new pieces. We are slowly getting more and more. There are certain elements when we're building these different vehicles, every year the same problems and challenges come up that we have to find ways to build our way out of. And there's certain things that even in today's portfolio, there's hundreds and hundreds of pieces, but that doesn't necessarily cover every possible situation. So there is certain gaps in the portfolio that we will doodle little ideas. For example, when we were doing the Aston Martin Valkyrie, I saw the car, I love the car.

And one of the reasons I knew it would be tricky, but there were two things that's great about that, because we are a returning team every year, it keeps us motivated. If you do a supercar every year, a few details might be different, but the majority's going to be the same. So you lose a little bit of engagement. So that's another reason for picking different vehicle types. It is also to keep the internal motivation of the team because then every year you're finding completely new challenges you have to overcome.

It also allows us to push the boundaries. The Valkyrie did that. People in my team were like, "We can't build that." And I was the complete opposite. Because I said, "That's what makes it exciting. Right now, you don't think we can build that. I can't wait for you to show me how to build that." But the only way that we could do it was we needed a new windscreen, which we knew from day one. We would need a new windscreen.

Now the challenge within that is that we are a LEGO system. All of our pieces work together, and they all are fixed scales and sizes and dimensions because a piece from 50 years ago has to work with a piece from today.

When we are doing that, we can't just create basically a die-cast copy of the windshield. We need it to fit into the LEGO system. So it'll always be a caricature of the windshield because that windshield needs to be reusable on products for the next 50 years.

All the elements that we've created, nine times out of 10, we tried to think very holistically, not just for Speed Champions, but for the whole LEGO portfolio. But what we've tried to do is every year tackle more of a target group for our vehicles. So in 2020, the focus was scale. So we made larger chassis and things like this to get the proportions correct. 2021, we focused on the scale of the wheels to make those more accurate to the new scale of the vehicles.

In 2022, we said headlights. So one of the biggest things we talked about internally is that not everybody likes placing stickers. So we wanted all of our headlights or taillights to be either brick built or decorated. Now in order to do that, we needed to make new headlight pieces. And they would have to be left and right because of the nature of the vehicles, that we could decorate and print completely differently to capture the many different shapes of headlight on the vehicles but would basically be one design. So it would be one element design that you can repeat on 50, 60 different vehicles, or you could use it without decoration on a Ninjago Dragon or on a Mario model or something. I've even seen them on the latest Buzz Lightyear products.

It's designed for us to work on multiple of our vehicles, but we design it in a way where it can be used on many, many different product lines and play themes and all those things. And that's basically the way that I've normally approached features is every year let's tackle a major area that's going to benefit all of our products. And then, one or two specific elements.

R&T: The Valkyrie is interesting, because there's something with that set that would lend itself more to one of the extreme Technic builds. Something that has thousands of pieces, whereas you're doing about 300-ish pieces per model.

CS: For the vehicle, it's around that 300 mark. Some go slightly over. The good thing about Speed Champions is it's a fixed scale. We always base it around the character, so we have to have a fixed scale.

R&T: I guess, when you talk about the details, you say that on certain models, there's certain details that need to pop out. What are the things that you are a huge stickler about to make sure that the team gets right so that you know that car looks like the actual car that's coming out?

CS: I always highlight one detail in every car. For example, we did the Nissan GT-R NISMO, and the taillights, it has to be the taillights. If it is, for example, a Dodge Charger, I would say it's the mouth, the metal frame around the mouth. I don't say, "Every car you need to nail the headlights. Every car you need to nail the side profile."

I'm probably the biggest pain in the backside to my design team because where most people would highlight one or two details, and I always do, I just give a list of everything. I write down two or three key points, but I literally sit down one-to-one and this is why I have this open policy because the designers can come to my desk as well.

And we just literally look at the car and we've got reference images and we normally get a die-cast model from the different partners or if it's a brand new car that it's too early for die-cast to exist, we get 3D CAD. We're super critical. We are our own worst nightmare. We're more critical on ourselves than anybody can be online.

I've always said that I find criticism much more valuable than people just complimenting. Because we cannot improve if people say, "Yeah, that's great. Next." But if you tell me, "Oh. Yeah, I like it. But this part wasn't right." Great. Then you give me exactly what I need to work on the next time.

We can also do cheats. So there's a lot of times where we'll get the scale of a vehicle and the dimensions. We'll make it the exact scale, but it looks weird in LEGO form compared to the real thing. So sometimes we might make the vehicle slightly shorter than it should be just to make it look more accurate in the LEGO form. So there's little areas we can break the rules of authenticity, but nine times out of 10, it's always about meeting the authenticity.

Saying all of that, that's just our internal process. We also work very closely with our IP partners. I really like to have a weekly conversation going and get as much feedback from those guys, invite them to visit us. Sometimes they can throw complete spanners in the works that we don't understand.

A good example of that would be the Mercedes Project ONE. We worked on it for a long time, and we were like, "It's not perfect, but this is pretty good." And then they saw it, and they were like, "Yeah, it should be longer." And we were like, "Crap." Their feedback is as valuable as anybody in our design team so we made it one module longer. They preferred it. We were just like, "We preferred it one short." But it all ties back to leaving our personal opinion and egos at the door.

Because the way I say it to all the partners we're fortunate to work with is, "This is their baby." They've worked years on the Project ONE or a Valkyrie or a, I don't know, a Koenigsegg Jesko. They've refined every detail. We're just babysitting for a little bit. So for us to say, "No, we know better than you guys." That's not an option on the table.

R&T: Right now, how far out are you working?

CS: I have a three-year plan. So normally, I would've planned out till '25, '26. I did (our second half 2022 products) both the James Bond DB5 Aston Martin and The Fast and the Furious Dodge Charger myself. That's something that I have been pushing and driving for three years to get greenlit internally.

I basically mapped out a whole 10 year strategy. So I was thinking 10 years ahead because we were trying to get that off the ground internally. There's a lot of loops to go through. Right now we've just finished our '23 first half-year products.

R&T: What do you drive? I know you said you're in Denmark, so it's very expensive to have a car there.

CS: I have an Opel Corsa. It depends where you're located because I go from England. So we call them Vauxhall Corsas. And then, apparently, when I came to Denmark, I found out that is not a European thing.

R&T: The taxes are so high and everything's so expensive in Denmark that it makes sense to have a Corsa.

CS: The biggest challenge, or not challenge, the biggest embarrassing thing is, my cousins and my friends and everybody back in England, they all drive Audis and Mercedes and BMWs. And I'm driving an Opel Corsa, the same type of thing I drove when I was like 17, 18. And I'm just like, "One day I'm going to be an adult and buy a real adult car." That's my dream.

R&T: Yeah. I mean one day for all of us. Before you worked at LEGO, were you a home builder? Were you creating and working on a model?

CS: Our design team is very diverse. We've got guys who never designed anything in their lives, no design education. They're just die-hard, what they call AFOL, so the Adult Fan of LEGO. So they do a lot of that home building or you see those guys on LEGO Masters and stuff.

I'm from a different group. I'm from the guys who have actually been trained to design. I've got a degree and I went through university with industrial design. When I was offered the job of designing at LEGO, I probably had a strange reaction because I didn't realize people designed LEGO. I just never thought about it. I was young and naive and I just thought like, "Oh yeah, someone has to clearly design that." I never thought about the concept. And that's quite common for a lot of guys where when you go to design school, you get told about designing chairs and tables or vehicles or day-to-day products. You don't really talk about designing toys so much. So that was quite a fun discovery.

R&T: You get to work with something that makes people happy all the time. It seems like a dream.

CS: Absolutely. I mean, the first time I worked with McLaren was like 2014. That was before we launched any product. That was when we were going to visit them and meet the and we all got picked up from the airport in a McLaren with a chauffeur because we can't drive them and they're only two-seaters. And I remember I was like, "Wow, I'm 23 years old. I'm getting picked up by chauffeur in the top of the range McLaren from the airport to go to a business meeting at their headquarters."

And most of my friends were just out of university, were either looking for jobs or maybe working in a supermarket or something while they were applying. I've been extremely lucky to end up where I am and to work with some of these amazing brands.

I never try to forget that some people dream about these cars and one day getting to visit Lamborghini or Ferrari and stuff. So when I get those opportunities, I try not to neglect them because what might become a routine for me, maybe visit them once a year or every two years or so, somebody out there, sat there waiting, dreaming to one day get the chance. We need to keep our feet on the ground a bit when it comes to that. That's what we try to do on our team.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos