How the painter Albrecht Durer fled the plague – by going monster-hunting

1519 had been a bad year for Albrecht Dürer. His patron, Maximilian, the Holy Roman Emperor, had died, leaving him without a steady income. All that surety, gone. Dürer is in bad shape, said his closest friend, Willibald Pirckheimer.

He was the most famous artist north of Italy, but Dürer was worried. His 48-year-old body was beginning to fail him. If I lose my sight and dexterity my affairs will not be good, he said.

More than ever, he was ruled over by the melancholy of Saturn, whose influence had always dogged him. All his life he had lived in his imagination. Was it all downhill from now on? He had to take control of the situation. Hearing that Maximilian’s heir, his 19-year-old nephew, Charles, was to be crowned in the Low Countries, Dürer planned to follow and petition for a new pension.

But he had a far more pressing reason to leave Nuremberg. The plague was raging in its narrow streets, and the heat of summer was about to make things worse. Those who could afford it were fleeing the city. And so, on July 12 1520, Dürer, his wife, Agnes, and their maid, Susanna, set off, travelling west, towards the coast.

We know how it all panned out – this journey through the heart of Europe, by horse and by boat, down rivers, to the sea – because Dürer wrote it all down. His diary of the year-long trip is the most complete record of his daily life we have, and it is the least interesting.

Dürer had always been a journeyman – a journey being a day’s work as well as a day’s travel – and his journal is filled with expenditure and income, the opposite of his wild imagining. Four centuries later, in 1913, when the Bloomsbury artist and critic Roger Fry edited Dürer’s journal, he was surprised to find that the artist’s attitude as a traveller was essentially contemporary, as if he had a Baedeker to hand.

The great artist was reduced to boring details, forever reporting how he’d shown his passport from the prince-bishop of Bamberg and they let him go free at the border; adding up exactly how many florins he spent on a bottle of wine or what he paid for his shoes; or exchanging engravings for an Indian cocoa-nut, a Turkish whip, two parrots in a cage, a fur coat made of rabbitskin, a piece of red chalk, fir cones, a shawl, and a little ivory skull.

Fry was exasperated. What was his hero doing with so many childish curiosities, all those sugar canes and buffalo horns? And how came it, Fry said, that we hear so little of great Flemish works of art? The way he exchanged his beautiful works for parrots! I find a poor fool of an artist like that really touching.

Neither of them realised that all this clutter and accounting was a disguise, a cover for his childlike wonder. He seemed to be concerned with grown-up bills, but Dürer was shoring up his imagination with the glorious thingness of things. He was a little boy sitting on the floor of the museum, drawing a dinosaur.

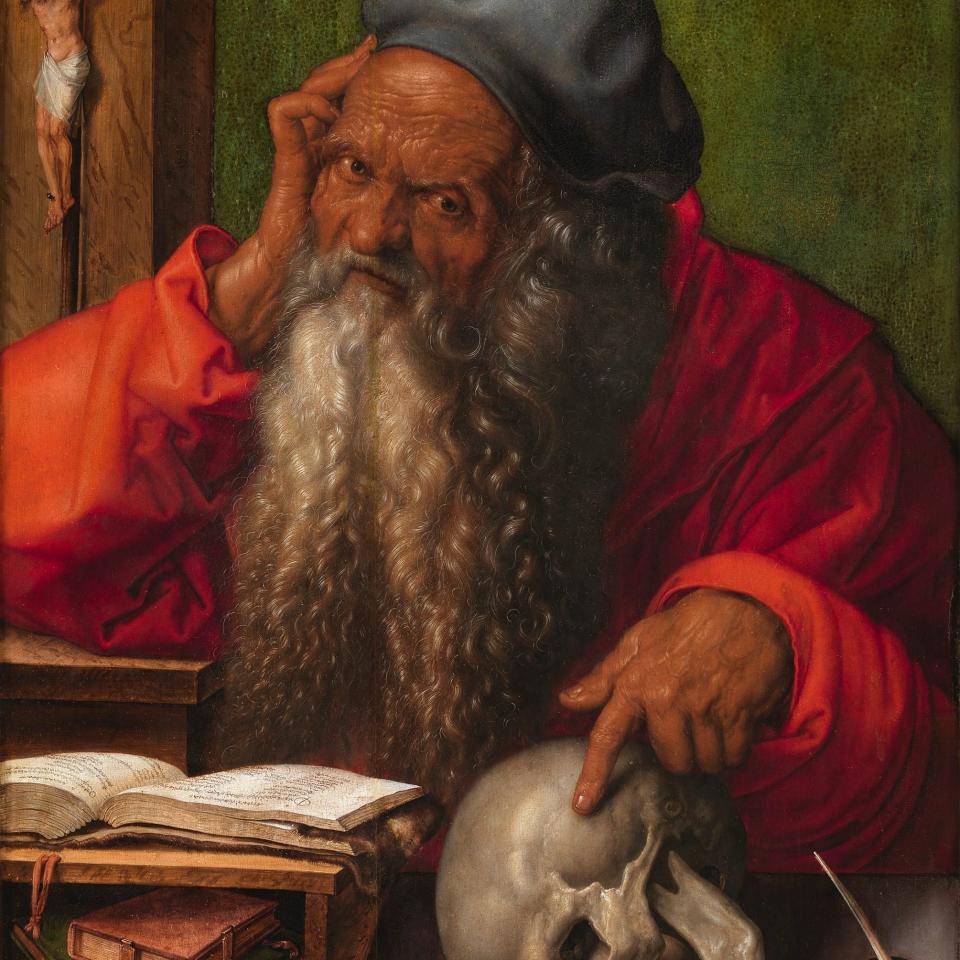

The artist spent that summer of 1520 selling and giving away his work, seeking new diversions, new sensations. To Lazarus Ravensburger, a German trader, Dürer gave a print of St Jerome in his cell, plus three large and expensive books. In return, he received a big fin, five nautilus shells, two dried fishes, a white coral and a red coral; plus four bamboo arrows, and four silver and five copper medals. It was a good deal, so far as he was concerned.

He sent great chests of this stuff back to Nuremberg, but he would only trust a friendly priest with his most treasured acquisitions: a large tortoiseshell, a buckler of fish-skin, a long pipe, a long shield, a shark fin and two little vases with citronate and capers. In an age of extraordinary trade, Dürer was trading in dreams.

“I have received 8 fl. in all for 2 prints of Adam and Eve,” he noted, “1 Sea-monster, 1 Jerome, 1 Knight, 1 Nemesis, 1 Eustace, 1 whole sheet, further 17 etched pieces, 8 quarter-sheets, 19 woodcuts, 7 of the bad woodcuts, 2 books, and 10 small woodcut Passions.

“I bought a pair of socks for 1 stiver.”

He was entertained in princely cities, from Cologne and Brussels to Antwerp, where the painters’ guild stood up on both sides of the table as he was led into dinner. He was their lord for the day; they tried to get him to stay.

Antwerp was the wealthiest trading port in northern Europe, and it was getting ready for the coronation. Dürer watched the procession like a boy at the carnival, holding a stick of paper streamers. The pole-candles and Frankish trumpets passed by, and the Three Holy Kings rode on great camels and on other rare beasts, very well arranged, and at the end came a great Dragon which St Margaret and her maidens led by a girdle. But Dürer was about to witness something even more sensational. Not on parade in the streets, but in the town hall.

“I saw the bones of the giant,” he marvelled in his journal. “His leg above the knee is 5½ft long and beyond measure heavy and very thick, so with his shoulder blades – a single one is broader than a strong man’s back – and his other limbs. The man was 18ft high, had ruled at Antwerp and done wondrous great feats, as is more fully written about him in an old book, which the Lords of the Town possess.”

These relics – a shoulder blade, rib, and some bristly stuff like a broom – were said to have come from a slain giant whose hand had been chucked into the sea, giving the town its name: ant, hand, and werpen, thrown away. In fact, they were the bones of a bowhead, an Arctic whale that may live for three hundred years; rivalled only by the Greenland shark, one of whom born in Dürer’s time could still be swimming in the dark green sea today. It was impossible, even for an artist, to imagine such creatures and to conjure up what flesh had clad those bones.

And no sooner had Dürer seen these remains than another display came his way. In Brussels town hall he saw a vast monstrosity, which looked as if it were built up of square stones. “It was a fathom long,” he said, “very thick, weighs up to 15 cwt., and it has the form as is here drawn.” His sketch hasn’t survived, but in his eyes these bones were almost architecture.

Whales had a habit of bedecking buildings with their ribs and their suffering. In the Cathedral of St Stephen in Halberstadt, Saxony, for instance, a vertebra, thought to have belonged to the fish that swallowed Jonah, hung from a pillar as protection against flood. In Kraków cathedral, the jawbone of a whale joined the bones of a woolly rhinoceros and a mammoth. In London’s Palace of Whitehall, a courtyard was named Whalebone Court on account of the bones arrayed there. In Verona, a whale rib swayed from an arch in the street the way a lover might hang over a balcony. In Pieter Saenredam’s painting of 1657, another rib dangles from Amsterdam town hall. Merchants sit round chatting, ignoring the judgment over their heads.

Dürer was stirred by such wonders; for an artist they presented a great challenge and allure, since they were so difficult to comprehend. Like God, no one could agree what they really looked like, or what they might be capable of. Dürer knew better. He’d been reading about these creatures since he was a boy.

The 13th-century monk, Albertus Magnus, was the first modern writer to describe, with any degree of accuracy, the appearance and behaviour of whales. His great work of encyclopedic brilliance, De animalibus, written in 1250, was only published in 1478, when Dürer was seven years old. It was a heady introduction. Recorded in Albertus’s compendium were 113 mammals, 114 flying and 140 swimming animals, 61 serpents and 49 worms. Dürer crouched over it in awe.

Then came the news he was expecting.

“At Zierikzee in Zeeland a whale has been stranded by a high tide and a gale of wind. It is much more than 100 fathoms long. No man living in Zeeland has seen one even a third as long as this is. The fish cannot get off the land; the people would gladly see it gone, as they fear the great stink, for it is so large that they say it could not be cut in pieces and the blubber boiled down in half a year.”

Dürer’s heart beat faster. He couldn’t afford to miss this beast. It could turn his life around, more surely than any imperial pension. One hundred fathoms, six hundred feet? That was a prodigious measure, by any means.

The medieval world knew that the whale showed how deceptive the devil could be, assuming the shape of an island or a tree, or the mouth of hell itself. Dürer ought to have known better than to go fishing for such monsters. You could smell them a mile away.

On St Barbara’s Eve, Dec 3 1520, Dürer rode north from Antwerp to the seaside. He’d prepared for his expedition by buying three pairs of shoes, a pair of eyeglasses and an ivory button.

“We passed by a sunken place,” said Dürer, “and saw the tops of the roofs standing up out of the water. Zeeland is fine and wonderful to see because of the water, for it stands higher than the land. The great ships sail about as if on the fields.”

They tried to get a sight of the great fish. But the storm tide which brought him in took him away again. All that effort and nothing. The men stood down. The monster, too awful to witness, fled of his own accord. Dürer started to feel unwell.

“A strange illness overcame me,” he said, “such as I never heard of from anyone. And this illness I have still, four months later.”

Some would claim his malady was malaria – bad air – as if this were a poisoned place. Dürer’s abortive, amphibious expedition would shorten his life, from a condition he couldn’t name, because of an animal he didn’t see. It was an extraordinary irony. Dürer had fled the plague at home for a healthier place, only to contract an infection from an infested shore. Yet it gave him new inspiration, as if he’d breathed in the whale’s bad air.

His sense of mortality allowed him to see anew, even more clearly. He’d always been restless, unable to stay still; his hand could never stop drawing. His trip to the Netherlands, far from marking the decline of his talent, was the most important event of his later years, his biographer, Erwin Panofsky, would say.

In 1522, Dürer made his last self-portrait. Naked, dishevelled, assailed by fever, his muscles had begun to sag. His clenched hands clutch a scourge and a flail. The art of painting also preserves the figure of a man after his death, he said. His locks blow in an interior wind, his mouth half open, trying to speak. His eyes, wonky, look out of the picture.

“And then he told us” – Pirckheimer reported – “how sometimes in his dreams he seemed to live amongst things so beautiful that if such only really existed he would be the happiest of men. But at the end he was withered like a bundle of straw, and could never mingle with people.”

Albert and the Whale is published by Fourth Estate at £16.99 on Thursday. To order your copy call 0844 871 1514 or visit the Telegraph Bookshop. Dürer's travels will be the subject of an exhibition at the National Gallery, London WC2 (nationalgallery.org.uk) later this year