A pair of supermassive black holes are stuck in a collision between galaxies. Astronomers caught the chaos on camera.

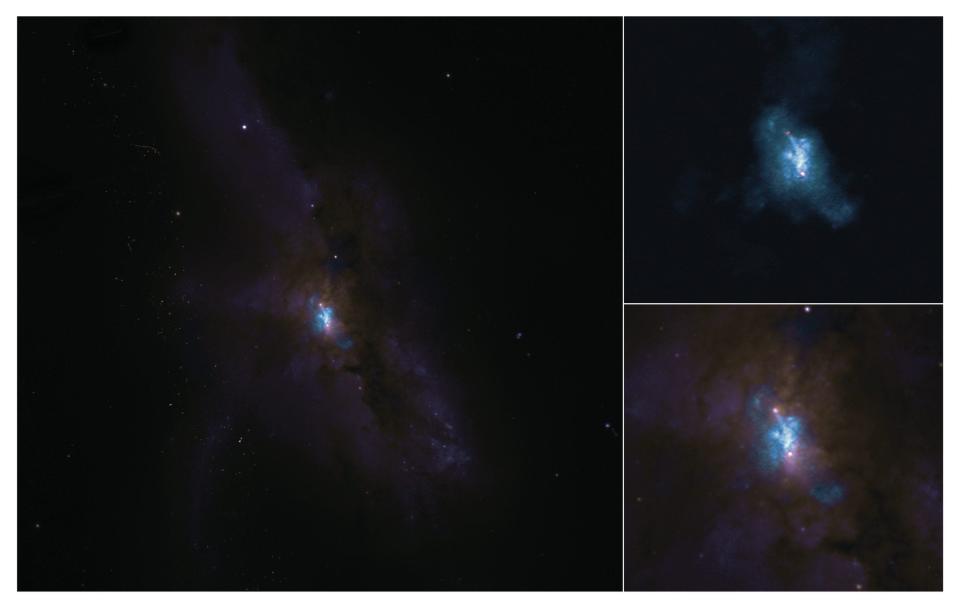

NRAO/AUI/NSF, S. Dagnello

Astronomers have captured a photo of two supermassive black holes caught in the collision of two galaxies.

The galaxies are merging to form a new galaxy, called NGC 6240.

The image suggests that the two black holes are much less massive than astronomers anticipated.

It takes more than a billion years for a pair of galaxies to merge.

But in the constellation of Ophiuchus, about 400 million light-years from Earth, two galaxies are almost ready to become one.

The galaxies are in the process of violently crashing into one another. Astronomers estimate it will take them another 10 to 20 million years to fuse completely; at that point, they'll form a new galaxy called NGC 6240.

Both galaxies contain a supermassive black hole in their center, and those are expected to merge as well.

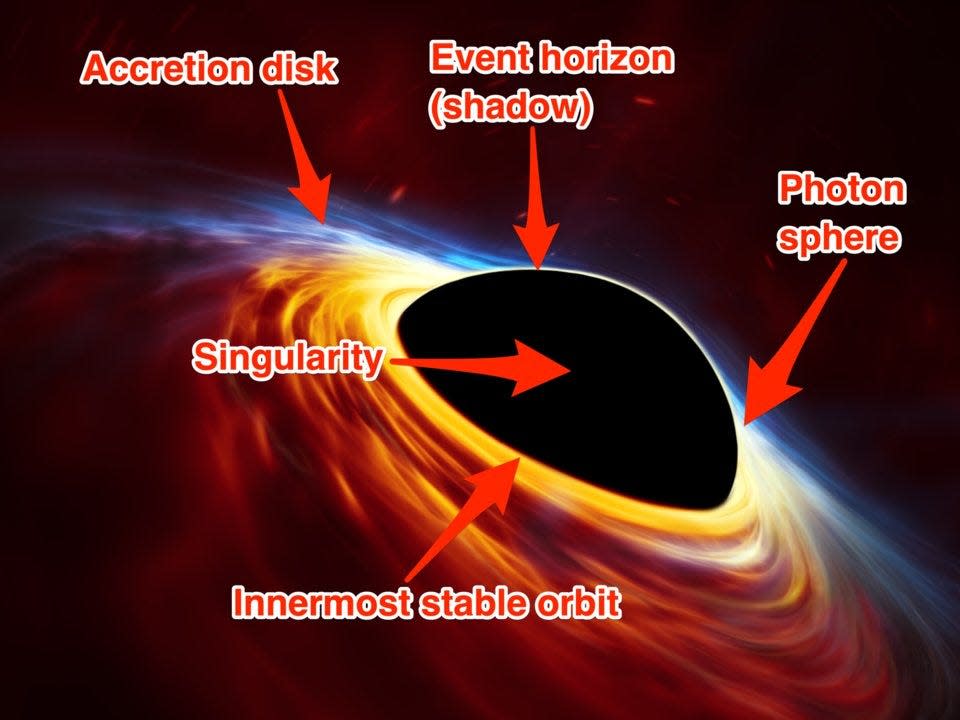

This whole process is difficult to capture on camera, however. Black holes' gravity is so strong that nothing can escape — not even light — so astronomers attempting to see them have to rely on light from the matter that gets sucked in (before it disappears). The first-ever photograph of a supermassive black hole was published in April 2019.

But an international team of astronomers recently captured a sharp photo that shows how two supermassive black holes are caught in the galactic collision that's forming the NGC 6240 galaxy.

The astronomers used the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA), a powerful telescope funded in part by the US National Science Foundation, to assemble the image. They presented their research at the annual meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Honolulu, Hawaii, on Sunday.

The black holes themselves aren't visible in the photo, but you can see the glowing gas that surrounds them (the blue stuff in the images below).

ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), E. Treister; NRAO/AUI/NSF, S. Dagnello; NASA/ESA Hubble

That gas is located within the black holes' "sphere of influence" — the innermost region of a galaxy where the black hole is the dominant force of gravity. The two black holes are feeding on the gas, which causes them to grow bigger as the galaxies merge. Previous images weren't able to capture this gas in such detail.

'A chaotic stream of gas'

Ezequiel Treister, an associate astronomy professor at Pontificia Universidad Católica in Santiago, Chile, told the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) that the gas doesn't form a rotating disk, as some scientists anticipated.

"We don't find any evidence for that," he said. "Instead, we see a chaotic stream of gas with filaments and bubbles between the black holes. Some of this gas is ejected outwards with speeds up to 500 kilometers per second. We don't know yet what causes these outflows."

Gas that isn't ejected from the sphere of influence will likely get sucked into the black hole.

The black holes are less massive than researchers expected

ESO, ESA/Hubble, M. Kornmesser; Business Insider

The image also challenges astronomers' ideas about the masses of these particular black holes. By observing the photo, the team found that a lot of the gas was stuck in the spheres of influence instead of the black holes themselves. That means the black holes are much less massive than anticipated.

Until recently, astronomers believed that the supermassive black holes in the NGC 6240 galaxy had a mass equivalent to about 1 billion suns. The new photo suggests, however, that the black holes are about as massive as a few hundred million suns.

The finding suggests black holes involved in other galaxy collisions could also be smaller than expected.

"This galaxy is so complex that we could never know what is going on inside it without these detailed radio images," Loreto Barcos-Muñoz, a researcher at the NRAO, said in a statement. "We now have a better idea of the 3D structure of the galaxy, which gives us the opportunity to understand how galaxies evolve during the latest stages of an ongoing merger."

Our own Milky Way galaxy is expected to merge with the nearby Andromeda galaxy in about 4 billion years.

Read the original article on Business Insider