The pandemic put school dress codes into perspective: 'We want control of our lives'

The first day of school this year turned out to be a pivotal moment for 13-year-old Sophia Trevino – and not just because it marked the beginning of the end of her middle-school career.

Trevino, along with more than a dozen other girls, says she was disciplined shortly after arriving that day at the Cobb County, Georgia, campus. The tips of her longest fingers had extended beyond a hole in her jeans, meaning her carefully selected, mom- and friend-approved outfit violated the school’s dress code.

The school’s strict enforcement of this seemingly arbitrary policy didn’t sit well with Trevino. What was so bad about ripped jeans? Why were girls being singled out? Why were masks optional in her district when certain other attire wasn’t?

“If masks are our choice, the clothing on our body should be too,” Trevino said. When the school offered remote learning in the early days of the pandemic, she regularly wore shorts and “got used to being comfortable.”

Trevino, with the help of her mom, launched a petition in August challenging the policy, eventually gathering nearly 5,000 signatures. They also made shirts denouncing dress codes as “sexist,” “racist” and “classist”; every Friday, Trevino and her friends, including boys, wore the shirts in protest. Her campaign garnered the attention of local and national news media.

Dress codes have long been a galvanizing debate among students. In 2021, that activism bubbled up again – this time intensified by politicized debates swirling through education, plus kids' pandemic-era revelation that they can learn in pretty much any attire.

After months of remote learning – and the more relaxed clothing norms that accompanied it – students are more inclined to question certain clothing requirements. They’re also more cognizant of the power of their voices and the equity implications of school policies amid heightened debate over topics such as critical race theory and transgender students’ rights.

Then there’s the tug-of-war over mask requirements, which in some states have been banned or, in certain districts, disregarded. The school board in Cobb County made masks optional, underscoring for Trevino the extent to which double standards are baked into dress codes.

“Young people understand that (dress codes are) a form of control over their identity, their personality and other much bigger and more important things,” said Shauna Pomerantz, a professor at Ontario’s Brock University who studies girlhood and dress codes.

Rules for attire, she said, are related to issues of gender, race and class, "and the idea that being looking white, middle-class and heterosexual is the best, most appropriate, most professional way to look.”

Stay in the know: For more education news and other can’t-miss moments of the day, sign up for Daily Briefing.

Dress codes: A self-fulfilling prophecy

Proponents say dress codes allow students to concentrate on their learning while preparing them for the professional world. They also can help keep students safe, supporters argue, particularly by banning clothing that contains hate speech, for example, or signals a gang affiliation.

At the start of this school year, districts sent out letters and held board meetings to reinforce or otherwise emphasize student dress codes. In some cases, school leaders reminded staff of their attire rules, too.

Administrators may feel especially inclined to enforce such standards this school year.

For starters, mask requirements can mean students’ appearances are already under extra scrutiny. (At least one school system in fact tried to add a mask mandate to its dress code, partly to depoliticize the requirements.) Plus, lots of students are still adjusting to the formalities of school and grappling with the trauma of the pandemic. Dress codes, the thinking goes, can help instill a sense of structure.

But many critics have said attire policies tend to target certain groups – typically girls, children of color and gender-nonconforming students – while also scapegoating them for problems that are out of their control.

'You can't win': Those infamous edited yearbook photos and society’s obsession with girls' bodies

Dress codes often rationalize, whether explicitly or implicitly, that certain attire can be distracting for boys. That “sends the message to girls that what they’re wearing is more important than what they think,” said Sabrina Bernadel, a fellow at the National Women’s Law Center.

Analyzing the dress code policies of roughly two dozen districts in New Hampshire, a 2020 study found such policies are far more likely to target girls than they are boys. “It puts the responsibility for ‘male urges’ on females to solve,” said Todd DeMitchell, a University of New Hampshire professor emeritus of education law and labor who co-wrote the study.

According to DeMitchell, dress codes in turn become a self-fulfilling prophecy: In an effort to de-sexualize girls, school dress codes often end up sexualizing them by focusing on how their body can arouse their peers.

And not all girls are treated equally, experts say. Those who are bigger or Black tend to be penalized at higher rates than their thinner, white peers – whether because they’re more developed (meaning they’re more likely to have cleavage, for example) or perceived as more sexual.

“Black girls are often policed (for dress code violations) because they are adult-ified,” Bernadel said. “They’re seen as older, more sexually knowledgeable; their body is curvier. So we punish that.”

Pandemic learning highlights double standards in dress codes

North Carolina’s Warren County school district decided to eliminate its uniform requirement earlier this year after realizing it exacerbated the problems it was trying to solve. The district had adopted the requirement in an effort to save families money and cut down on discipline problems. But when the pandemic hit, parents came forward saying uniforms created financial burdens rather than removing them, said Keith Sutton, the interim superintendent.

Warren County schools, he said, replaced uniforms with a gender-neutral dress code that avoids punitive measures but encourages students to dress appropriately. Prohibited attire includes bedroom slippers, halter tops, lounging pants and clothing with "vulgar, profane, racially charged or suggestive words or pictures."

“We’ve seen the social-emotional impact on students coming out of the pandemic. … Having to worry about a particular (uniform) is one less thing they have to consider,” said Sutton, who will begin his term as permanent superintendent in January. “We’re encouraging, supporting, developing a mindset … preparing them in a way that helps them determine what is professional, business-casual attire.”

Sutton believes the change would’ve come about without the pandemic, but online learning expedited it – just as dress codes in the corporate world have been relaxed in the world of remote work.

Striking a balance between structure and fairness is especially important now as students return to in-person learning. Students may have learned from home wearing spaghetti straps and leggings without that clothing impeding their lessons. They may also be grappling with the residual trauma of the pandemic. The last thing they need is to be disciplined for their outfits.

“People are realizing that punitive dress codes and other sorts of appearance policies really serve little to no pedagogical purpose … especially when pitted against a global health crisis,” said Bernadel of the National Women’s Law Center. They’re “starting to see that what’s important is keeping students safe and making sure they’re able to learn – not policing what they look like.”

For young people, the issue is symbolic, Pomerantz said. “The dress code issue has really crystallized for so many young people that they have political interests and that they're willing to fight for something.”

And that fight can feel especially urgent amid broader social reckonings over gender, race and identity.

'I am not alone': Gen Z activists unite amid COVID pandemic to confront racism, mental health

“Students are much more attuned now to discrimination that’s taking place on the basis of sex and race,” Galen Sherwin, a senior staff attorney with the ACLU’s Women’s Rights Project, said in a press call.

The ACLU is involved in t dress-code-related lawsuits that are making their way through the courts. In one suit, three families are suing a charter school whose now-suspended dress code required girls to wear jumpers, skirts or skorts. That suit is now before the full 4th Circuit Court of Appeals, which heard oral arguments this month.

Separately, the ACLU has sent letters to various school districts in Florida urging them to revise their dress codes. One such district, St. Johns County south of Jacksonville, infamously photoshopped yearbook photos to cover girls' chests.

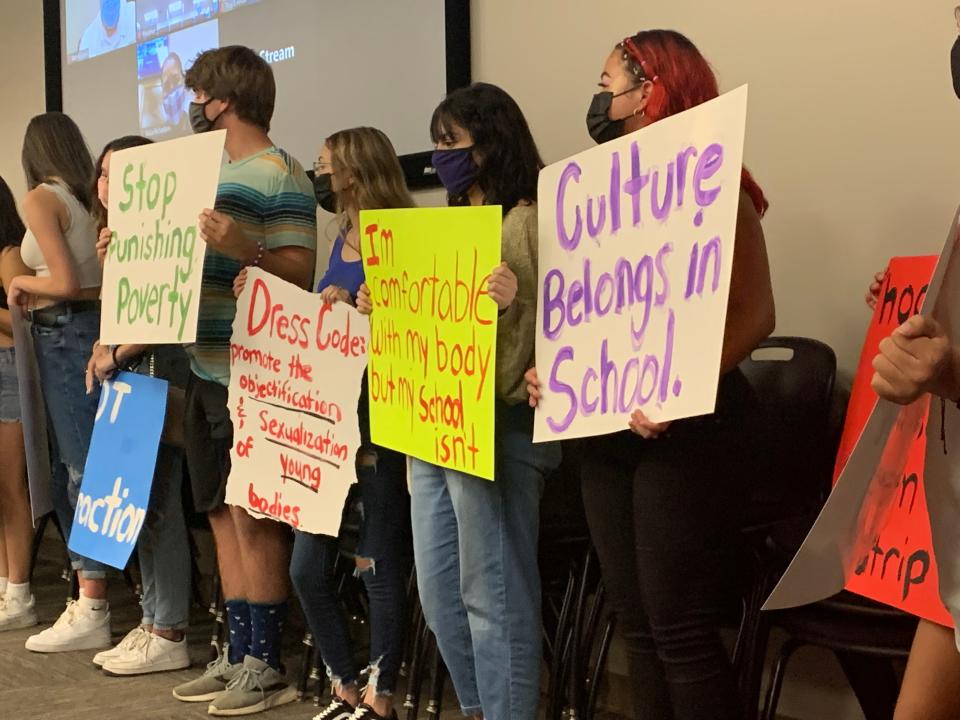

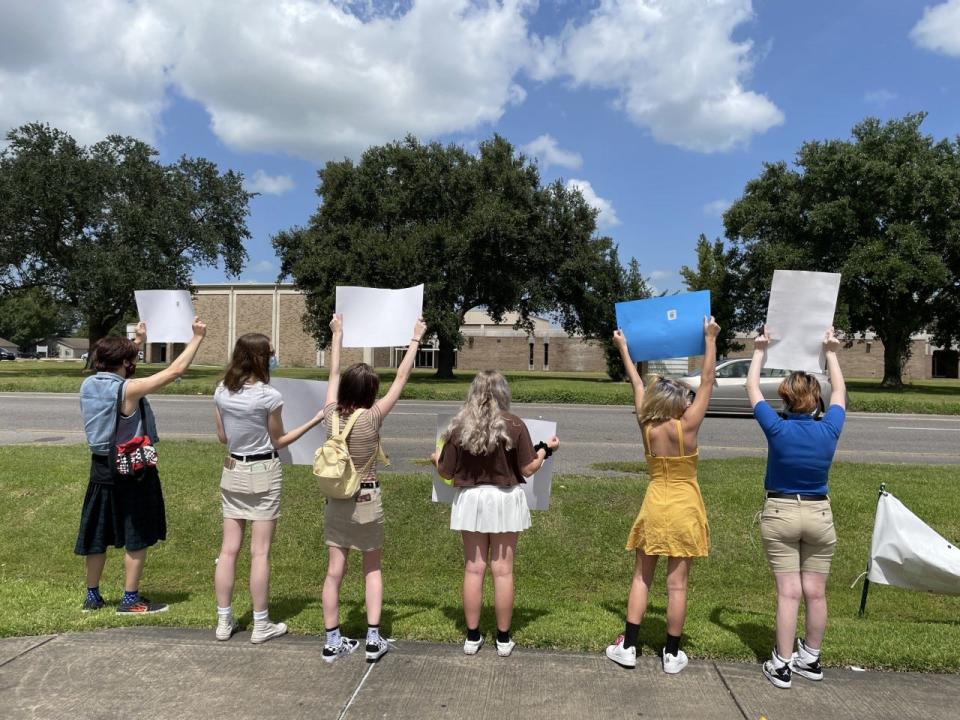

In other places, from Southern California to Chicago, students have, like Trevino, demonstrated and launched petitions challenging their schools’ dress codes. (Many were disciplined, if not detained, for their participation.)

Canada has seen a flurry of student-led dress code protests in recent years, including a high-profile campaign that resulted in Toronto’s new attire policy. That policy is now a model for student activists, including Trevino.

Trevino’s school has yet to change its policy on paper, she said, but these days staff hardly enforce it, which she believes is at least in part a response to her activism. And she hopes the fight continues as her peers across the country follow in her footsteps.

“We’re getting older,” she said, “and we want control of our lives.”

Contact Alia Wong at (202) 507-2256 or awong@usatoday.com. Follow her on Twitter at @aliaemily.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: School dress codes: COVID pandemic led to protests among students