As pandemic spreads, the Cuban government moves to silence independent journalists

When Cuban independent news site 14ymedio recently scooped the government and published the regime’s plans to charge for food in dollars, the news spread like fire on social media, causing waves of disbelief and frustration among Cubans.

Cuba’s head of state, Miguel Díaz-Canel, was furious.

“Yesterday, they went to social media to say: These people are going to dollarize the economy, they are going to close the stores in [local currency] and they are going to sell everything in foreign currency. And the working people — who they ‘worry’ so much about — who earn in local currency ... are going to be totally helpless,“ Díaz-Canel said in a July 17 address in which he officially announced the sale in dollars and other measures to deal with the severe economic crisis triggered by the coronavirus pandemic, increased U.S. sanctions and dwindling support from Venezuela.

“They have taken only one measure — of course, they do not know the others — and they have bombarded [the internet] with all their resentment and all their hatred,” said Díaz-Canel, visibly irritated on state television.

While independent journalism has existed for years on the island, sometimes tolerated by the government and sometimes not, it has recently found a big enough audience to pose a challenge to state-controlled media.

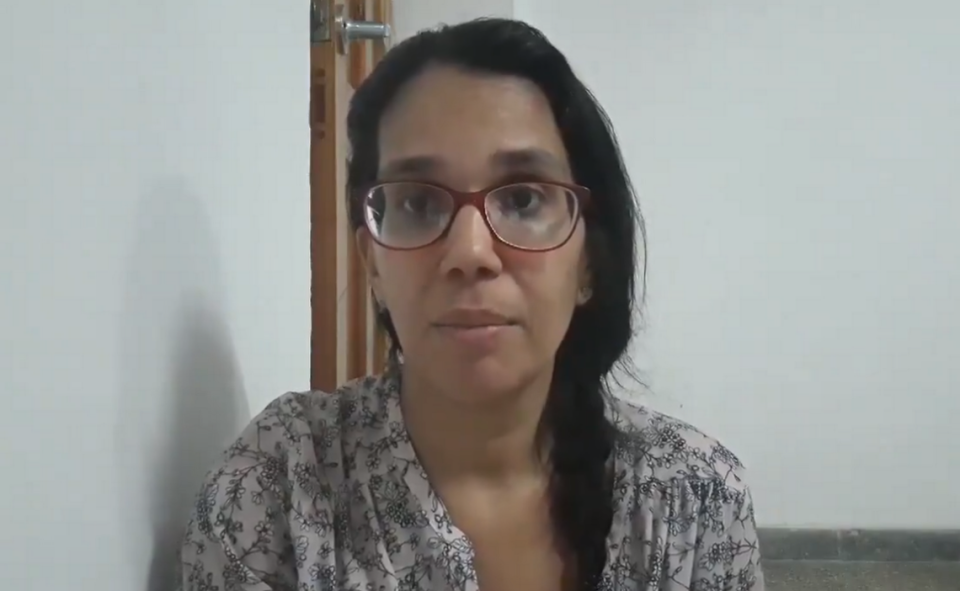

Díaz-Canel’s reaction shows the mismatch between the government’s desire to keep a tight rein on the media and reality, says Luz Escobar, a journalist for 14ymedio, the digital news site founded by blogger and journalist Yoani Sánchez in 2014.

“The first time that we got that tip, we asked, ‘But how is it possible?’ We started making calls, and after the third source, we went ahead” and published, Escobar said.

For decades, the Cuban government has harassed independent media, which is not legally recognized. Journalists employed in private outlets are labeled “mercenaries” and are routinely arrested or forced to leave the country. In the past, few Cubans could read what independent journalists wrote because the government blocked digital sites, and most of the population did not have access to the internet.

But in recent years, when authorities could no longer delay widespread use of the internet in the 21st century, independent media and information sharing on social media have become a headache for Cuban authorities and the Communist Party, which directly oversees state media. The threat to the Communist Party’s monopoly over the news has become all the more evident after authorities finally allowed internet access to mobile phones in late 2018.

Currently, more than a dozen independent media compete with official outlets such as Granma and Cubadebate. Some are based in Cuba, but others are produced from the United States, Spain, or Mexico, although most have journalists on the island, including some who left their state jobs. They are financed through advertising, donations, or financial aid from institutions, nonprofits or foundations linked to foreign governments.

The Cuban government still blocks some of these websites, but they have learned to circumvent censorship through mirror servers or by teaching their users to use virtual private networks to access their content.

The government’s reaction to the flourishing of independent journalism on the island has not been subtle.

In August last year, independent journalist Roberto Quiñones, who writes for the Miami-based news site Cubanet, tried to report on the trial of a religious couple from Guantánamo who demanded homeschooling for their children, which is prohibited on the island. Quiñones was not allowed to write about the judicial process and ended up serving a one-year sentence under charges of “disobedience.” He was released Sept. 4.

“We journalists live in a critical situation because the internet is super expensive, the sources are not at hand, nor the data. We work in a very hostile environment. They can arrest us, prevent us from leaving the house, remove us from an area where we are reporting ... and they do not need a warrant to do so,” Escobar told the Miami Herald in a phone call from Havana.

Another Cubanet journalist, Camila Acosta, posted on Facebook a short video that she managed to make of her recent arrest when she was sitting in Havana’s Central Park.

“The harassment began when I started my work with Cubanet. They automatically regulated me; that is, they did not allow me to leave Cuba,” Acosta said in a WhatsApp interview. “Then they began doing to me what they do to other activists: On specific dates, they do not allow us to leave our homes. Recently, they have evicted me from the apartments I have rented in Havana.”

Acosta also said that she was fined for violating Decree 370, which regulates the use of the internet on the island and establishes penalties against those who disseminate, “through public data networks, information contrary to the public interest, morality, good manners and the integrity of the people.”

Silencing journalists during a pandemic

The law has turned into a censorship weapon, as the government struggles to control information about COVID-19, several journalists and international organizations have said.

In May, 47 independent media and human rights organizations came together to warn that the government was using that law to persecute journalists and activists, “particularly in the wake of the health crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic.”

“We believe that the increase in harassment is due to the tensions and insecurity that the government feels due to the economic and social crisis generated by the coronavirus and the increased economic pressure from the U.S. government,” said Hugo Landa, director of Cubanet.

Several journalists from El Estornudo, another independent outlet focused on literary journalism, and Diario de Cuba, a news site based in Spain, have also been arrested or fined in recent months. Amnesty International issued a statement condemning the “worsening” censorship of independent journalists who have been fined for reporting on the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on the country.

“The increase in repression suggests they have a higher perception of risk, of instability, that the situation may get out of their hands,” Escobar said.

She said the Cuban government particularly dislikes the questioning of its response to the coronavirus. When authorities began to report the first local cases back in March, journalists and activists criticized the delay in closing schools and airports.

“Journalists and activists put pressure on social media for that to happen because the Ministry of Tourism was inviting people to come to Cuba to ride out the quarantine,” she said.

As tourism officials were touting Cuba as a “safe” destination for foreign travelers in mid-March, an el Nuevo Herald investigation found an unusual increase in acute respiratory diseases that experts attributed to undiagnosed coronavirus cases. At the time, the health system lacked resources for extended coronavirus testing, and the government never gave a public explanation about the data.

Until the end of July, official reports of infections and deaths suggested the pandemic was under control. But since the beginning of August, Havana, where the virus continues to spread, has been under a tight curfew.

Despite scarce resources and zero access to official sources, independent journalists have asked uncomfortable questions and, at times, reported new outbreaks before they appear in the official media. But the work is very difficult because the government is the only source of data on the coronavirus pandemic on the island.

“In the context of COVID, the intimidation of hospital sources, including patients and doctors, has escalated. I know of several cases of medical students and doctors who have been punished for talking to the press,” Escobar said. “That is terrible because it ... paralyzes the flow of information and makes officials the only source of data and information regarding this.

“There is not much firsthand information about COVID because there is a lot of repression to prevent information from getting out,” she added.

And the information they do get comes at a high price.

Escobar cannot travel abroad, although the authorities have never officially told her in writing why not. On several occasions, she has found a police officer or a State Security agent stationed at her building entrance to stop her from leaving her house. And she has been questioned and threatened by the police.

Then there’s the toll on her family.

“When you have children, it is difficult to go through this because you try not to let them suffer the consequences,” said Escobar, the mother of two girls.

The last time she was placed under house arrest, she said, “it took me by surprise. I was going down the building with the children, and they saw all that. You try to explain to them that you have a complicated job, and the government doesn’t like it, but it creates that feeling that you are like living in a movie. Because I would love to have a normal life and for them to see my profession as something normal.”

Follow Nora Gámez Torres on Twitter: @ngameztorres