Pandora Papers reveal new details about how a Miami businessman out-trumped Trump

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Orestes Fintiklis thrust himself into the public eye with an audacious acquisition of a Panamanian luxury hotel that sported the surname of the 45th U.S. president, Donald J. Trump.

The Cypriot, who resides in Miami, wowed local media in Panama and Florida less than a year later in March 2018 when workers crowbarred Trump’s name from hotel signs, one letter at a time.

The Trump Organization’s management unit, which had a lucrative contract, was tossed out in the process, and that became the subject of ongoing litigation.

In the end, the bowtie-wearing pianist and his Panama-based investment firm artfully vanquished the famous New York real estate dealmaker.

But Fintiklis shared two particular traits with the man he outmaneuvered — a penchant for secrecy and knowing how to tap influential friends.

Documents found in the Pandora Papers, made public on Sunday in a massive leak of 11.9 million confidential documents from offshore companies and the 14 law firms that helped create them, reveal new details about the very private Fintiklis and his acquisition of the Trump Ocean Club International Hotel and Tower, now converted to a Marriott.

It was an acquisition of a property already shrouded in both secrecy and irregularities. The first financier was a Brazilian who after being charged with fraud and forgery involving another deal became a fugitive. The developer who saw the project through filed for bankruptcy after defaulting on bonds that raised the money to build the futuristic, sail-shaped, 70-story condo and hotel.

Much of the Trump hotel saga in Panama is well known. But there has been little attention on Fintiklis, now 42, who at the time of his bold move left much of the world wondering, “Who is that guy?” One former senior Panamanian official at the time described Fintiklis as someone “nobody ever heard of, even in Panama.”

The Fintiklis acquisition was carried out by his Panamanian private equity company Ithaca Capital Partners, which by definition is a limited partnership that does not have to make much public. The Pandora Papers show Ithaca, relatively small by Wall Street standards, used a network of mostly anonymous companies in the British Virgin Islands, Delaware and Panama to create a complex business structure.

That web of complexity was stitched with help from a top Panamanian law firm specializing in secrecy, a firm whose ownership is interwoven into the very fabric of Panamanian politics.

Revelations

The Pandora Papers were obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, then shared with more than 600 journalists across the globe — including those at the Miami Herald and el Nuevo Herald and the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP).

Among the major findings from the leak were secret property holdings in the United States by King Abdullah II of Jordan and gobs of celebrities and athletes hiding their fortunes or seeking to minimize their tax exposure.

The leak proved revelatory in Panama too, where the past two presidents — Ricardo Martinelli and Juan Carlos Varela — were found in the documents, along with politicians past and present. Martinelli cut the ribbon on the Trump hotel. Arrested at his Coral Gables home and extradited to Panama, Martinelli was cleared of corruption charges in 2019. His two sons were indicted by U.S. prosecutors in July 2020 for allegedly facilitating bribery in the Odebrecht scandal. Varela was questioned by Panamanian prosecutors about donations from Odebrecht, the Brazilian engineering firm that paid hundreds of millions in bribes in South America to win business.

Ties that bind

The Pandora Papers shined a spotlight on the law firm Alemán, Cordero, Galindo & Lee (aka ALCOGAL), putting the powerful Panamanian firm in the public eye. It’s founder Jaime Alemán in 2009 was appointed Martinelli’s ambassador to the United States, a position Alemán’s father had also once held.

In his 2014 book “Honesty is Priceless,” Alemán heaped praise on the Eletas, one of the oldest, most influential family business dynasties in Panama. The Eletas are the largest coffee exporter in Panama, and are big players in the energy, real estate and media sectors.

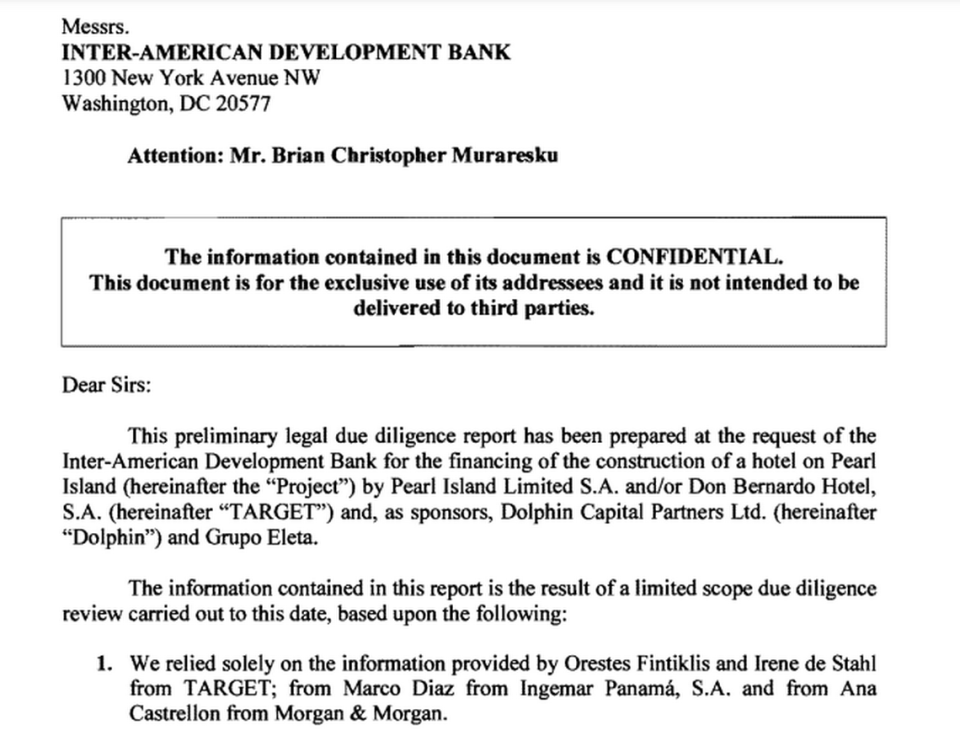

The Pandora Papers show that Fintiklis has relied on ALGOCAL for his dealings in Panama since 2008, when the Greek investment firm in which he was a partner, Dolphin Capital Partners, joined forces with Grupo Eleta.

Fintiklis appears on numerous confidential ALCOGAL documents — before his Trump hotel victory — with Eleta executives.

Fernando Eleta, the family patriarch who died in 2011, served as finance and foreign minister of Panama decades ago and negotiated a draft deal that eventually became a blueprint for the return of the Panama Canal to local control. He appears frequently in the Pandora Papers for companies created with the help of ALCOGAL during the final decade of his life.

There are other Fintiklis revelations in the documents.

A letter dated May 26, 2016, from ALCOGAL is addressed to Fintiklis in Cyprus at WinWin Estates. The letter laid out a fee schedule for legal services in the acquisition of most of the assets of the Trump hotel’s insolvent developer, Newland International Properties Corp.

Documents in the Cyprus corporate registry for a company called WinWin Estates Limited show a Fintiklis family business with his father and brother. The company’s website touted WinWin’s services to help foreign investors get Cypriot residency if they invest in approved real estate in Cyprus.

Cyprus actively encouraged visa-linked real estate investment, but it was compelled to end it under pressure from the European Union, which last October threatened action.

WinWin has not been tied to any wrongdoing.

The EU warned that the popular scheme — known for attracting politically exposed persons and criminals, among others — posed a risk “to security, money laundering, tax evasion and corruption.” Russians and Chinese were among the most aggressive users of the “golden passport” program.

Disclosure blind spot

Is there an overlap between investors coming to WinWin Estates and the investor base of Ithaca Capital? It’s nearly impossible to know. Fintiklis is not required to disclose his private equity investors — not in Panama and not in the United States.

“Private equity funds are a blind spot if they are operating in these locations, and even in the U.S. as well,” said Dev Odedra, who spent years in the compliance departments of big global banks before launching his own British anti-money-laundering consultancy Minerva Strategem Consulting.

These financial firms argue that fears are exaggerated because money is tied up in long-term investments and cannot easily be removed.

“People have this false notion that nothing suspicious happens here,” Odedra said.

The only disclosure requirement is on investors in the limited partnership, who must report their earnings to authorities wherever they claim tax liabilities.

The lack of public disclosure is compounded by a lack of required reporting in many countries, including the United States, about the beneficial, or true, owners of shell companies.

A story from the Panama Papers leak in 2016 detailed how those who ran hedge funds and those who invested in them used anonymous shell companies for nefarious purposes.

“So we literally are carving a path, mapping out to bad guys where you should put your money if you want to hide it,” said Gary Kalman, U.S. director for anti-corruption watchdog Transparency International.

There is no record of Fintiklis ever being accused by regulators of financial crimes anywhere. Fintiklis declined to comment for this story.

Foreign backers

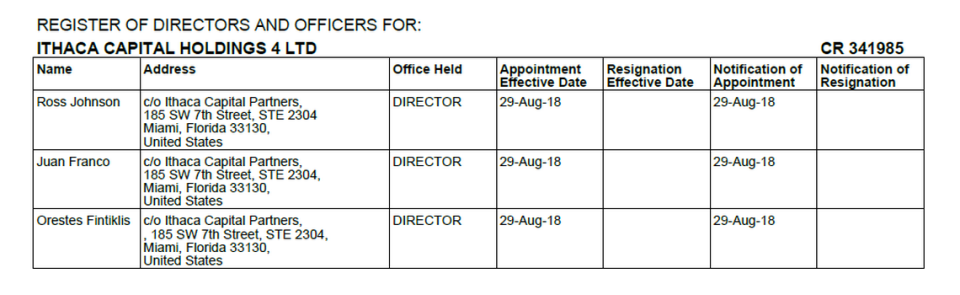

While Ithaca is publicly silent on investors, the leaked documents show that Fintiklis and Ithaca Capital had directors from Colombia and Ecuador listed on documents prepared for the acquisition and in some company formation documents.

One director identified in the documents was Ecuadorian Thomas Ross Johnson, who owns a large flower export company called Rosaprima.

The other signatory was a Colombian named Juan Fernando Franco. He co-founded a company called Paymentez that processes payments for online gaming and mobile apps. It operates in nine Latin American countries.

Many companies in Panama use “nominee directors,” locals paid a small sum to have their signatures on documents as camouflage but who play no actual role. If successful businessmen like Johnson and Franco appear as signatories, it suggests they are stakeholders in Ithaca Capital.

Neither associate of Fintiklis returned comment requests by telephone or emails to their contact information listed in the ALCOGAL documents.

Panamanian friends

Before his Trump triumph, Fintiklis worked for the Greek real-estate investment firm Dolphin Capital Partners, whose Dolphin Capital Investors traded shares on the London stock exchange. Fintiklis was sent to Miami to seek opportunities in Latin America and homed in on Panama.

Dolphin partnered with the politically connected Eletas to develop a luxury resort and private homes on the pristine Pedro Gonzalez islands some 30 miles off the Panamanian mainland, accessible only by plane or boat.

The Eleta patriarch Fernando, a year after stepping aside as foreign minister, acquired the islands in 1969. The tiny airport on the islands is named after him today.

A decade worth of Pandora Papers documents show the web of shells and holding companies tied to the two partners in the luxury development project that came to be known as Pearl Islands. Among them is ALCOGAL’s original review of the purchase and land use rights.

The development triggered environmental concerns since it involved building on pristine islands that teemed with wildlife. It recently was the subject of a Latin American collaborative investigation into how locals have fared on the islands amid the development. The Ritz Carlton chain broke ground in 2017 for its private reserve on one of the islands in the archipelago.

Fintiklis appears in dozens of Pandora Papers documents for the island project alongside Fernando’s son Diego Eleta and grandson Guillermo St. Malo Eleta. The Cypriot is also close with Hugo Torrijos, a nephew of former President Martin Torrijos and great nephew of Omar Torrijos, the unelected “maximum leader” of Panama from 1968 to 1981.

Do these friendships extend to investment in Fintiklis ventures? The lack of any requirement of public disclosure or any registry of shell-company ownership makes that a difficult question to answer.

“The registries of beneficiaries are one of the most efficient and effective mechanisms,” argues Carlos Barsallo, the head of Transparency International’s Panama office, noting a similar lack of clarity exists in the United States.

Dolphin Capital Investors eventually sold to another Greek real estate group its 60% stake in Pearl Islands in January 2017, at a 27 million euro loss ($31.3 million today).

By then Fintiklis had already formed his own private equity fund the prior year and was acquiring through two Panamanian companies the majority stake in the troubled Trump-branded hotel and amenities.

Pulling it off

Fintiklis turned to the politically connected ALCOGAL for legal help in the acquisition, the same firm that developer Newland used when it built the hotel.

Newland had been in bankruptcy and needed to unload 202 out of 369 hotel condo units it controlled. Ithaca Capital Partners bought out Newland in August 2017 for $20 million, with financing from a small Panamanian lender called Canal Bank.

A top official at the bank was Roberto Brenes, a well-connected former CEO of the Panamanian stock exchange. Brenes was also involved in the Pearl Island project with Grupo Eleta, and is the stepfather of Grupo Eleta’s CEO, Guillermo St. Malo Eleta.

Brenes declined comment. St. Malo Eleta described Fintiklis as Dolphin’s in-house lawyer in the Pearl Islands project.

“Our business relationship was always positive and started and ended with that transaction,” he said.

The Pandora Papers also include the working drafts of what became the contract for Ithaca Capital to buy out Newland. One 34-page document, a November 2016 contract draft, featured handwritten notes splashed across the margins.

“No way we are going to sign tomorrow,” reads one hands-on comment with the initials O.F.

The same document lists Johnson and Franco below Fintiklis as buyers of the Newland stake, further suggesting their involvement in Ithaca.

Secrecy into success

Fintiklis was able to use the high profile acquisition of the Trump hotel to trampoline into other Latin American prize properties, including the W Hotel in Bogota.

But by 2020 the global pandemic wreaked havoc on the hotel industry everywhere. Seemingly against the odds, Fintiklis went out earlier this year and raised a whopping $245 million from Wall Street through a controversial kind of company now drawing scrutiny from the Securities and Exchange Commission.

He did so by forming a controversial entity called a blank-check company, Ithax Acquisition Corp. These “special purpose acquisition companies,” or SPACs, are empty shells that are looking for a company to buy and merge with — like cutting and pasting an existing business into the shell.

Fintiklis and Ithax have until Feb. 1, 2023, to complete a merger with another company or must return the millions in start-up money to investors.

Although the buyers of large swaths of Ithax shares are not public, Pandora Papers reporters obtained a list of investors. The top investors, like Ithaca itself, are in the business of buying up distressed companies on the cheap.

Blank-check companies have attracted the attention of critics and the SEC because they lack the transparency and investor protections of a traditional initial public offering (IPO).

Critics also note these companies often provide a windfall for founders like Fintiklis.

U.S. rules on SPACs require that Fintiklis, unlike his private equity firm, must reveal the management team for Ithax and file quarterly reports, called 10-Q’s.

The most recent 10-Q on Aug. 13 noted that Ithax has declared itself an “emerging growth company” exempt from many reporting requirements, including enhanced auditing.

More striking are the benefits Fintiklis potentially enjoys under the designation. Exemptions listed in the document include, “reduced disclosure obligations regarding executive compensation in its periodic reports and proxy statements, and exemptions from the requirements of holding a non-binding advisory vote on executive compensation and shareholder approval of any golden parachute payments not previously approved.”

And for Ithax itself, there’s the bonus of registering in the Cayman Islands.

“The Company is considered an exempted Cayman Islands Company and is presently not subject to income taxes or income tax filing requirements in the Cayman Islands or the United States,” the quarterly report said.

Miami Herald researcher director Monika Leal contributed from Miami. Journalist Scott Bronstein contributed from Panama, and Stelios Orphanides of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project also contributed.

Kevin G. Hall began the Pandora Papers project as an investigative reporter for the Miami Herald and continued the work as North America editor for the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project.

The Pandora Papers is a global collaboration between The Miami Herald and the nonprofit International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. If you like journalism like this, please make a donation to ICIJ to support it.