Paper exams, AI-proof assignments: Wisconsin college professors adjust in a world with ChatGPT

Something about the student's writing seemed off to Sam Harshner. The syntax was sophisticated. The topic choice was advanced. All this from a student who'd barely spoken in the first few days of Harshner's Writing and Argumentation class last fall.

Harshner, who teaches in Marquette University's political science department, ran the work through an online artificial intelligence detector. It came back all red.

Harshner ran his other students' work through the AI detector. He said eight of the 40 assignments, or 20%, came back with an 85% chance or higher of AI-generated work. The facts hit him like a gut punch.

"Honestly, like, you want to think what you're doing matters," Harshner said. "You want to think that at least in some part all the work you're putting in actually impacts people's lives."

AI is disrupting colleges across the country, offering shortcuts for students and uncomfortable questions for professors. Tools like ChatGPT can, in a matter of seconds, solve math problems, write papers and craft code on command.

"It’s entirely changed the way I teach," Harshner said.

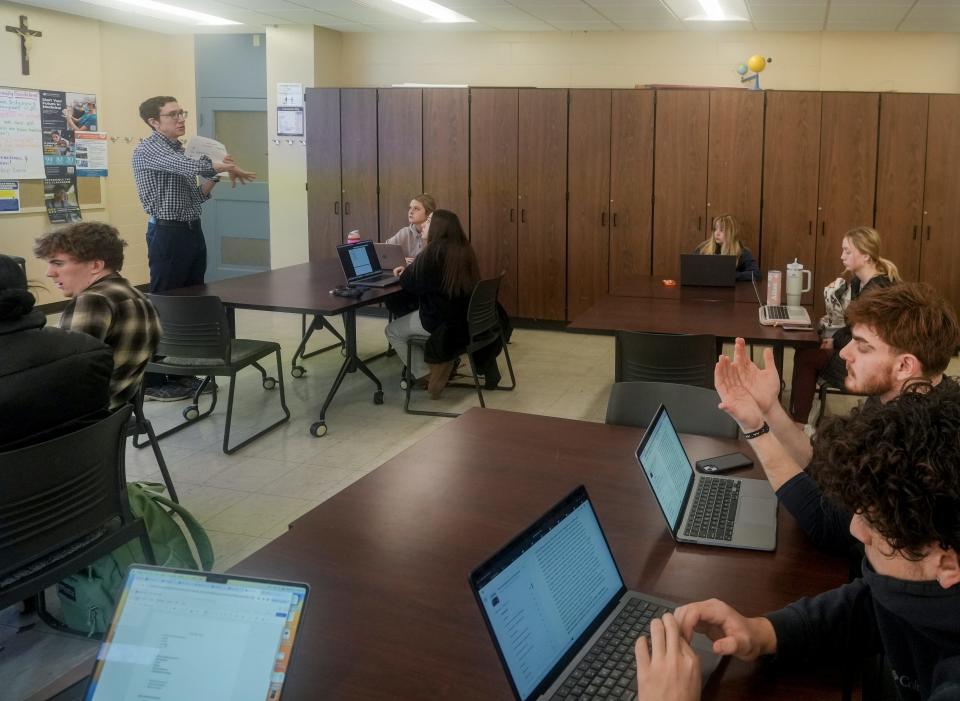

Harshner's writing-intensive course was previously heavy on take-home essays. He now has students write their papers during class. Not only does he outline an AI ban on his syllabi but he also has students sign a contract agreeing not to use it, even for generating ideas or paper outlines.

"You have to take steps to, you know, kind of push back on this," Harshner said, adding he believes AI is a "threat to higher education in real, meaningful ways."

College instructors rethink lesson plans

Not everyone is as alarmed as Harshner. Other instructors admit they've come across ChatGPT-written work students passed off as their own. But they believe the vast majority of students aren't outsourcing their assignments.

Even so, many are tweaking how they teach.

Some run assignments through ChatGPT to see how well the chatbot performs, and then make adjustments. Others incorporate AI into coursework to expose students to the tools of the future — and to highlight their limitations.

Gabriel Velez, a Marquette professor in the department of education policy and leadership, was surprised how few of his students knew about ChatGPT when he demonstrated it in class.

"The freshmen we're getting now, they've gone 12 years of education without using AI," he said. "I don't think just because it's become quickly available that they're going to jump ship and 100% dive into it."

Velez's own research supports this. He anonymously surveyed nearly 500 Marquette students last fall on their use of AI. Preliminary results found 66% of respondents said they don't use AI tools at all. Those who have said they most often turned to it when hitting a writing block or to generate ideas — a start rather than a crutch.

Another Marquette professor, Jacob Riyeff, used to ask students to write short summaries of readings ahead of class discussion. Deemed too tempting for students to turn to AI to complete the work, the English professor now hands out physical copies of readings and asks students to underline and analyze the text by hand.

"If it’s going to be really easy to cut corners, how are we setting students up for success?" Riyeff asked.

AI isn't a two-minute talking point during syllabus week in Riyeff's class. He said he has multiple discussions about his stance on AI with students throughout the semester.

"I want them to understand why I take this approach pedagogically," he said. "It's not 'because Dr. Riyeff says so.' That’s not the way to change hearts and minds, especially when they’re hearing lots of hype about this."

Eric Ely, who teaches in the Information School at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, has made some of his assignments more personal, asking students to write about topics that connect to their own lives. In a new assignment this semester, he has students engage with an AI chatbot and document the process.

"Part of my job is to prepare students for life after college, right?" he said. "This is the world that we're living in, and so I feel like I would be doing a disservice to students if I would not talk about this or limit or completely prohibit the use."

Ely sets clear expectations for which assignments students can and cannot use AI. For the most part, he believes students abide by the rules and turn in their own work. But he and his teaching assistants have talked about how sometimes it can be hard to tell.

Can professors easily detect AI-generated work?

The more Elena Levy-Navarro played around with ChatGPT, the more her worry about how well it could complete her assignments faded.

The chatbot's essays lacked specifics. Its arguments were vague. And when the UW-Whitewater English professor asked it about neo-Nazism, a topic often discussed in her class on 1930s fascism, the chatbot demurred. There were other tells, too, like when it cites nonexistent sources.

"I feel fairly confident I could tell if they’re using ChatGPT," Levy-Navarro said.

Levy-Navarro hasn't yet come across work she suspected was AI-generated, and that's why she hasn't dramatically changed her teaching approach. Her assignments often require close readings of literary texts.

Another English professor, Chuck Lewis at Beloit College, has come across a few cases of chatbot-produced work. It's important to craft assignments that are meaningful and engaging to students, he said.

Lewis predicted the standard five-paragraph essay to be "doomed." He believes he's created "relatively AI-proof" assignments.

The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel tested it out, asking Lewis and other instructors for one of their class assignments. The newspaper told them some of the homework would be done honestly and some would be handled by ChatGPT. But the professors weren't told who did the work until after giving a grade.

The Journal Sentinel's experiment found ChatGPT earned one A, two B's and two incompletes.

More: Can ChatGPT pass college assignments? We tested it out, with help from Wisconsin professors

For UW-Madison professor Dietram Scheufele, the big question isn't what AI can — or cannot — do for college students.

There's a commercial interest in improving the accuracy of AI, he said. Eventually, the idea of coding from scratch will disappear. Using AI to assist in the writing process will be the new normal.

"What I’m much more concerned about is the fundamental disruption to our social system and how we prepare students for that," said Scheufele, whose research includes technology policy, misinformation and social media. "The question for universities right now is why this degree will be worth something 40 years from now."

Is cheating on the rise?

John Zumbrunnen, the vice provost of teaching and learning at UW-Madison, said the most-asked question he gets about AI is whether the university has or will have a policy on it.

UW-Madison does not, meaning students navigate at least four different class policies per semester. In some cases, individual assignments will have their own AI expectations. That's why it's important, he said, for instructors to offer grace in this new world.

"The answer in the teaching and learning space cannot be one-size-fits-all," he said earlier this month at a UW Board of Regents meeting.

Riyeff, the Marquette English professor, serves as the university's academic integrity director. He said he hasn't seen an overwhelming increase in the number of AI-related plagiarism cases.

Still, some instructors said they have second-guessed their students while grading papers.

"I’m trying not to be suspicious all the time," Riyeff said. "It’s one of the challenges in this moment."

Contact Kelly Meyerhofer at kmeyerhofer@gannett.comor 414-223-5168. Follow her on X (Twitter) at @KellyMeyerhofer.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Wisconsin professors respond to AI disruption with new assigments