Parallels in critical race theory and graphic novel Maus bans sets concerning precedent in Tennessee | Opinion

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Both the banning of the book "Maus" in McMinn County, TN and the backlash to it is different from the response to banning the teaching of critical race theory. While both tamper with the teaching of histories that are difficult to confront, the differences prove instructive about the limits in thinking about the history of racism we have yet to fully tackle both in Tennessee and as a nation.

Proposed in 22 states and passed in 5, banning CRT is an orchestrated moral panic designed to silence teaching basic ideas about racism, like white privilege and unconscious bias, alongside claims that the United States “is fundamentally or irredeemably racist,” as the law in Tennessee puts it.

Aided by conservative Christian leaders, Right-wing anti-CRT laws and the campaigns at school boards to end it are an effort to chill the difficult conversations about our nation’s contradictions. Founded upon liberty and equality for all, we live in a country shaped by the history of slavery, Jim Crow segregation, lynching, and the resulting ongoing struggle for equity.

There are parallels with eliminating Maus from the curriculum in McMinn County. In both cases it is about the refusal to confront "objectionable language." This is what the McMinn County Board of Education focused on in Maus, just as those railing against CRT oppose "divisive concepts," as the Tennessee law states.

The school board’s justification was also about protecting eighth grade students from nudity in one image, which might make students feel uncomfortable, just as CRT might make white students feel uncomfortable about whiteness in the history of racism.

Hear more Tennessee Voices: Get the weekly opinion newsletter for insightful and thought provoking columns.

Differences are starker than the correlations

In the school board discussion in McMinn, unlike school boards roiled by the teaching of CRT, they made clear “we aren’t against teaching the Holocaust.” One teacher even insisted, “I love the Holocaust” even though she wouldn’t teach it using Maus. The apparent consensus that led to banning Maus was that it normalized vulgar language and nudity, leading to the unanimous decision to bar it, despite the fact that the entire unit on the Holocaust in the curriculum hinged upon it.

The vociferous backlash continues to unfold. If the response to Maus proves different from the response to CRT, and if this becomes a turning point to the banning of uncomfortable histories, especially for white Christian students, then this will have historical precedents.

In 1915, the Jew Leo Frank was lynched in Georgia. Frank ran a pencil factory in Atlanta where one of his employees, a young girl named Mary Phagan, was found strangled in the cellar. Frank was convicted in a controversial trial that aroused national attention. When his sentence was commuted by the governor, he was dragged from prison by a mob who lynched him in Marietta, Mary’s hometown.

While an exceptional and fraught moment for Jews in the South, the Leo Frank case was scripted by the history of the widespread lynching of Blacks. There was an important difference: in the aftermath of Frank’s lynching there was a temporary halt to lynching and his case helped to propel the anti-lynching campaign led by the NAACP.

Think also of the images painted by Marc Chagall in the late 1930s and early 1940s of Christ’s crucifixion. Chagall depicts Jesus wearing a Jewish prayer shawl or tallit, clearly marking his Jewishness. He did so to draw attention to the persecution of Jews in Europe, which was being overlooked by most Christian bystanders as the Holocaust unfolded, drawing attention to their cause.

These were both cases in which the crucified Jew rattled the white Christian conscience. The cultural unconscious shaped by the crucified Christ, who was of course branded as “King of the Jews,” plays out still.

Hear from Tennessee's Black voices: Get the weekly newsletter for powerful and critical thinking columns.

Our current society depicts history inaccurately

Think today about the use of Holocaust imagery in provoking outrage at perceived victimization, now happening on both sides of our contemporary debates in the culture wars.

Why do those who oppose vaccination mandates claim they are treated like the Jews during the Holocaust, some even affixing yellow stars to their clothing at rallies? It codes opposition to vaccination as a mark of martyrdom to a higher cause, and this resonates powerfully in the Christian conscience, even as this cultural appropriation disturbs Jews, some even calling it anti-Semitic.

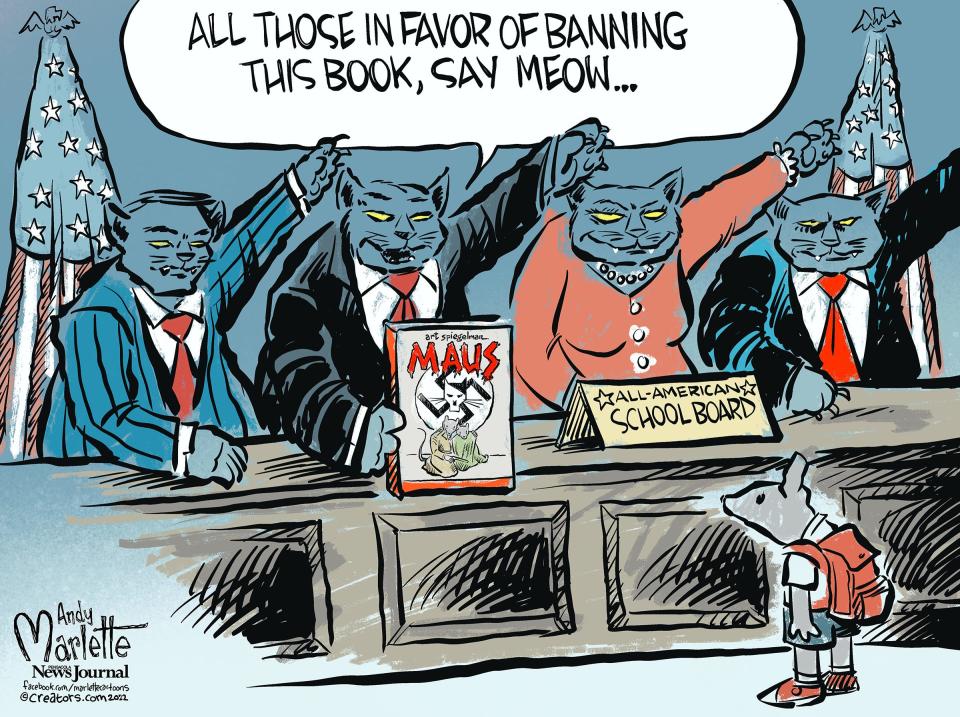

This is playing out on both sides of the culture wars. A recent cartoon published in newspapers about the banning of Maus quickly went viral. Clever in using the imagery of Maus to condemn the school board for banning Maus, it depicts the McMinn County Board as fascist.

The board members are portrayed as cats, like the Nazis in Maus. They give the Hitler salute in front of American flags as a bewildered cartoon mouse represents the school children in McMinn County as akin to persecuted Jews.

Is this identification with Jews and the Holocaust resonant with the white Christian conscience because of the place of Jesus as the sacred sacrifice to annul sin in the history of the West?

It would be good if the banning of Maus were a turning point in efforts to ban teaching about the history of racism, especially in the South, because we see its consequences when they play out on the bodies of white Jews in ways that are not recognized when they play out on the bodies of Black Americans.

It would be good if those who “love the Holocaust” and say they love Jews not least because Jesus was a Jew understood that the Holocaust cannot be understood except by facing its naked vulgarity, brutality, lynching, slavery, and murder in ways powerfully rendered by Maus so that even eighth graders can understand it.

It would be good if those who oppose cancel culture recognized that it is not only happening on one side of our cultural debates.

Indeed, it would be good if those on both sides of our cultural divide stopped splitting off racisms, opposing only anti-Semitism or anti-Black racism, xenophobia, or Islamophobia.

Ultimately what we need in our schools are more conversations about these difficult and uncomfortable topics, not censorship from school boards or legislation designed to silence them.

Jonathan Judaken is a Professor of History and the Spence L. Wilson Chair in the Humanities at Rhodes College

This article originally appeared on Memphis Commercial Appeal: Bans on 'Maus' book and critical race theory sets concerning precedents in Tennessee