When parents are the activists: PFLAG celebrates 50 years of LGBTQ advocacy

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In 1982, David Holladay was 16 years old and about to come out to his mother. They lived in a small town in Oklahoma and attended a Baptist church. This was the era of Rock Hudson and Elton John and Billie Jean King, people whose names, he said, “were never far away from something derogatory.”

When Holladay considered his future as a gay person, he saw it only as “the fog of the unknown.”

What Holladay didn’t know then was that a movement was brewing that he and his family would be a part of for decades to come. He hadn’t yet heard of PFLAG, the first LGBTQ ally organization for queer people and their families. But Holladay would eventually realize that by coming out, he wasn’t only doing something for himself but also for his parents: He was giving them an opportunity to stand beside him.

“They realized this isn’t about people demanding a huge spotlight or attention,” he said of his parents’ first introduction to the gay rights movement. “These are just human beings trying to make their way in the world, and one of them’s my kid.”

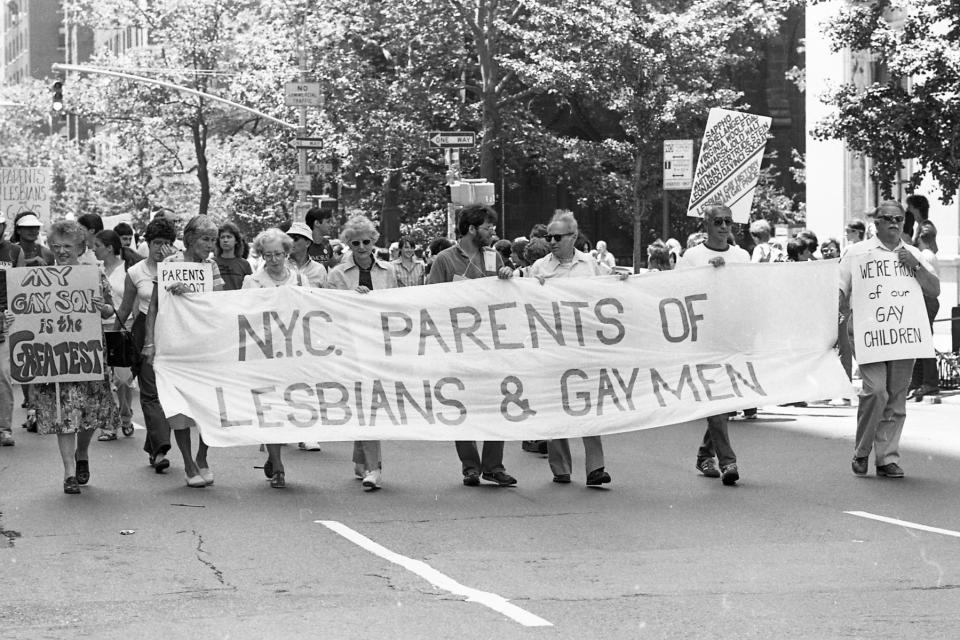

The parents of gays and lesbians were just beginning to gain visibility in the 1980s. They were slowly building a coalition that started with one mom in the early ‘70s: Jeanne Manford, an elementary school teacher from Queens, New York, who walked alongside her gay son, Morty, during the 1972 Christopher Street Liberation Day march (the precursor to New York City’s massive LGBTQ Pride March). Her sign was a call to action for others like her. It said: “Parents of Gays: Unite in Support for Our Children.” Manford is known as the first parent to walk in a pride march.

As Manford and her son walked, people whistled and clapped. She initially thought they were cheering for the guy behind her, but she soon learned otherwise. “They screamed! They yelled! They ran over and kissed me. ‘Would you talk to my mother?’ ‘Wow, if my mother saw me here.’ … They just couldn’t believe that a parent would do that,” Manford recalled in an interview years later.

The experience changed both Manford’s life and the course of allyship in America. The next spring, in March 1973, Jeanne and Morty Manford co-founded what was initially called Parents of Gays, or POG, in a church in New York’s Greenwich Village neighborhood. About 20 people attended.

POG would eventually become Parents, Families and Friends of Lesbians and Gays, and then, in 2014, it would become simply PFLAG. Now, 50 years after its founding, PFLAG has more than 400 chapters across the country and more than 200,000 members.

The organization celebrated its semicentennial at a gala in New York City this month. In attendance was Suzanne Manford Swan, daughter of Jeanne and sister of Morty. (Jeanne died in 2013 and Morty in 1992.)

“For 50 years, people have walked into PFLAG meetings worried about their loved ones. There, they learn that the people they love are still the same people they always knew and loved,” Swan said in prepared remarks, calling the organization “a beacon of hope, love and acceptance for millions of people around the world.” She also called on members to “recommit ourselves to the work that still lies ahead.”

The work is especially crucial for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer young people who do not have parents to advocate on their behalf. Many LGBTQ people still fear that they will be rejected by their parents, and queer youths are overrepresented among young people experiencing homelessness. And while these youths have higher rates of suicide than their non-LGBTQ peers, a survey published by The Trevor Project in 2019 found that LGBTQ youths who had at least one accepting adult in their lives were 40% less likely to have attempted suicide in the preceding year.

The Manfords founded PFLAG in a political environment in which homosexuality was still considered a mental disorder by psychiatrists. It was the years following the Stonewall uprising of 1969, and bars were still being raided. Gays and lesbians were being institutionalized against their will, and sodomy laws were strengthened to apply only to gay people and deny them custody of their children. Morty Manford, an activist in his own right, was a founding member of the Gay Activists Alliance and, in addition to co-founding PFLAG, worked to push gay rights legislation in New York, focusing on discrimination in employment, housing and places of public accommodation.

Jeanne’s activism was spurred two months before she walked in the parade. Morty had been protesting a meeting of a homophobic parody group, and he was beaten by a firefighter who threw him down an escalator. When the police called Jeanne to tell her Morty had been arrested, the officer added, “And you know he’s a homosexual?” This question was meant to humiliate Morty and alienate him from his mother.

“Yes, I know,” Jeanne said. “Why are you bothering him?”

Morty was hospitalized for several days. Two months later, he asked his mother to march with him, and Jeanne responded that she’d march if she could carry a sign. Reflecting on her activism years later, Jeanne said she was driven to do something because, “I’ve always felt that Morty was a very special person. And I wasn’t going to let anybody walk over him.”

A parent's call to action

If coming out is an invitation for activism, David Holladay’s parents were there to answer the call.

“Fortunately for me, when David came out I was in a large law firm in Oklahoma CIty. I was a partner in that law firm, so I didn’t have to be silent if I chose not to,” Don Holladay, David’s father, said.

But there wasn’t a clear path to how to proceed. “It was a fairly lonely landscape,” Don said. “Our biggest ally was the library.” They would find out about PFLAG from a Dear Abby column.

The Holladays formed a local PFLAG chapter in Norman, Oklahoma, in 1994. David’s mother, Kay, went back to school for a master’s degree in public education, ran for the city council and became a PFLAG board member. Don has gone on to advocate on behalf of LGBTQ people in his state and was the lead attorney in the fight to legalize same-sex marriage in Oklahoma.

“You cannot love someone the way you love your children and listen to rock throwers who aren’t throwing at you, but they’re throwing at your child, and not do anything about it. That just doesn’t make sense,” Don said.

When Kay heads to pride marches, she always makes sure to bring her sign, a fitting evolution of the one Jeanne Manford proudly carried: “I love my gay son," it says, "...and his husband."

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com