What parents and their children who stutter wish more people knew

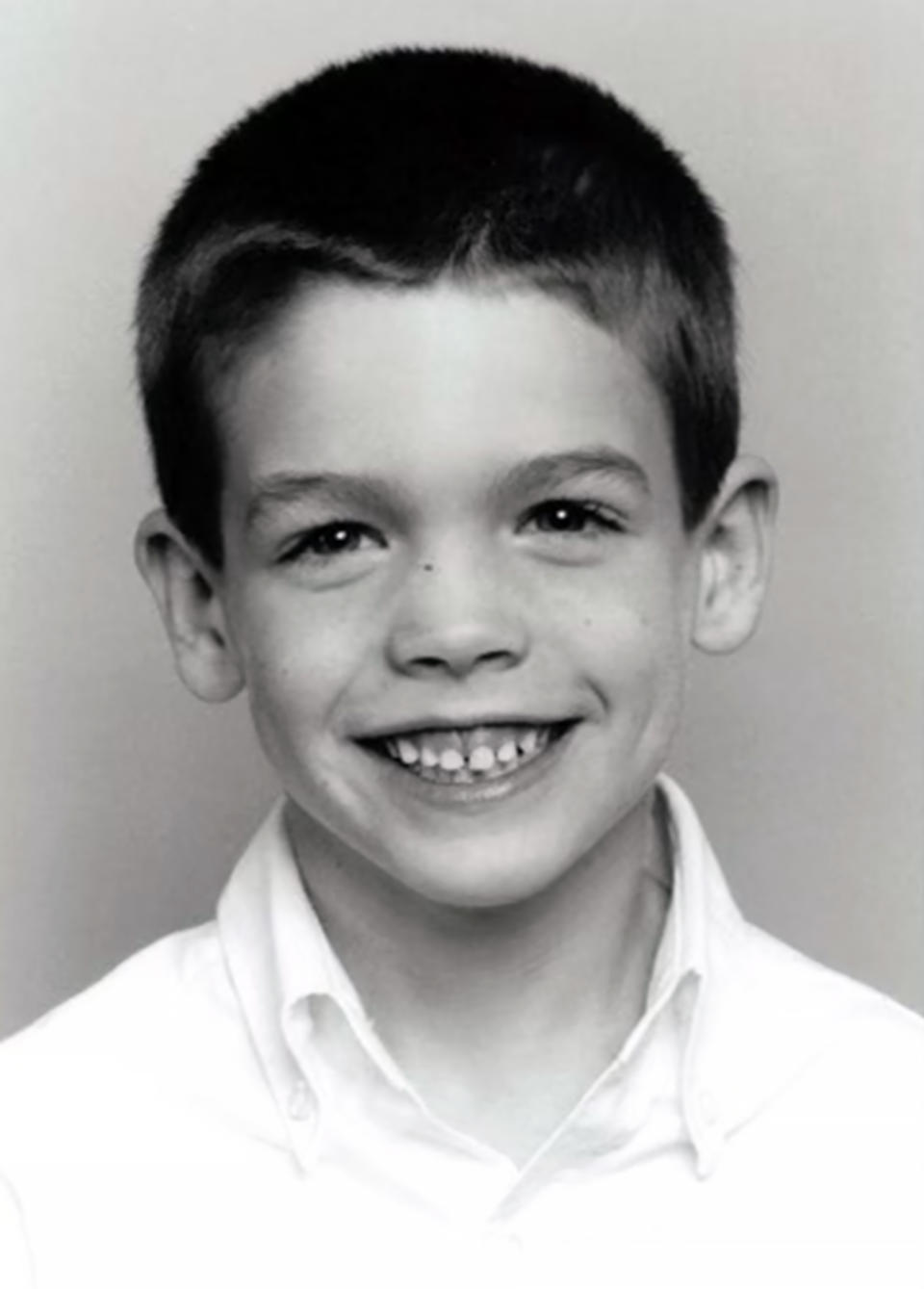

As his peers prepared for another school year, then 7-year-old Cameron Coppen stood in front of his first grade class, prepared to address them.

"I'm sure you have noticed that sometimes I get stuck on my words and I speak differently," Cameron would begin, his mom, Stephanie Coppen, says.

"Well, I stutter.'"

Cameron would then go on to describe what stuttering is and field questions from his curious classmates.

Then, his mom says, the school year could really begin.

Sixteen years later, the now 50-year-old mother of three says she can still remember the impact of her son's presentation.

"It just got the elephant out of the room — we all acknowledged that things are a little different for him when he speaks, and then it just ceased to be an issue," Coppen tells TODAY.com.

"That was our 'ah ha' moment: To teach him how to advocate for himself."

Almost 3 million U.S. adults stutter, according to The National Stuttering Association, a non-profit support network for people who stutter.

Still, misunderstandings, stereotypes and harmful depictions of the disorder remain, leaving people who stutter often feeling embarrassed, anxious or afraid to speak.

"People aren't stuttering because they're nervous. They're not doing it because they're unintelligent — it's an actual disorder," Coppen, who lives in Georgia, says. "What somebody who stutters has to say is just as important as what anybody else has to say: It just might take them a little longer to get it out."

What is stuttering?

The Stuttering Foundation, which provides free resources, services and support to people who stutter, defines stuttering as a "communication disorder" in which speech is disrupted by repetitions, prolongation or abnormal stoppages of sounds and syllables.

Approximately 60% of people who stutter have a family member who stutters too, and recent research suggests that people who stutter process speech and language differently than others, leading experts to believe that in addition to child development and family dynamics, genetics and neurophysiology play a role in the development of a stutter.

A reported 95% of children with the disorder will start stuttering before the age of 4, according to the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. The average age of onset is 2 years and 9 months.

Coppen noticed Cameron was experiencing "disfluencies" in his speech shortly after he turned 3.

"Initially, we didn't know what to think," Coppen said, adding that she immediately put Cameron in early intervention speech therapy with the goal of eradicating her son's stutter.

Over time, that goal changed.

"(Therapy) was a lot of stuff they wouldn't necessarily do with a child who stutters now," she explains. "It was targeted at trying to get him to slow his speech, which we now know doesn't help at all. As he got older, it switched to being more supportive."

Ellen Kelly, the vice president for professional development at The Stuttering Foundation, says the shift in stuttering therapy is a reflection of how far society has come in better understanding the disorder.

"Historically, speech language pathologists were taught to work toward a 'cure'," Kelly, who is a psychologist and speech language pathologist, tells TODAY.com. "When stuttering is the way you naturally speak, that's impossible. So now, there's a shift: It's about communicating with your voice, and if that voice includes stuttering, well, that's your voice. Interestingly enough, oftentimes when you stop fighting it the tension and struggle reduce."

Kristine Short, 48, watched that shift occur in real time after she paired her then 3-year-old son, Caden, with a speech therapist who said they specialized in stuttering.

At first, Short was encouraged to ignore her son's stutter and "not bring it up" — advice she now says she wishes she had ignored, especially as her son entered first grade.

"We weren't saying anything about it to him, but we were taking him to speech therapy twice a week," she explains. "He didn't know why he had to do something that wasn't fun."

Initially, she says she also viewed speech therapy as a way to "cure" her son's stutter.

"It's hard to look back and see that you've made some pretty serious mistakes with your children," Short adds. "For me, one of them is that I gave my son a goal that wasn't attainable or realistic. He tried and was doing his best, but it made him not want to talk to us at all. Every time he would (speak), we would say, 'Slow down, use your techniques.' He thought we didn't care about what he was saying, just how he was saying it."

Ultimately, Caden stopped speech therapy when he was 10. He's now a 21-year-old senior at New York University majoring in American studies.

The importance of representation for people who stutter

Both Coppen and Short say that, as children, their sons had never met someone who stutters until they attended support groups.

"I was reluctant, because at that time I was still thinking that Caden's stutter was going to go away. Why would I need support for something that was temporary?" Short says. Ultimately, she attended a National Stuttering Association "Family Fun Day" event.

"I remember leaving and Caden said: 'I knew that there were people that stuttered, but I never knew anyone who stuttered,'' Short adds. "His whole face lit up."

Historically, television shows and movies depict people who stutter as being incompetent, untrustworthy or idiotic. It wasn't until the 2010 film "The King's Speech" was released — a historical drama showing King George VI’s effort to overcome his stutter — that, Kelly says, widespread representation started to change. The movie was written by a person who stutters.

"The more we tell these stories and write about them, and get the information out there, the more we can dispel the myths," Kelly says. "That's what slowly starts to change society."

President Joe Biden has discussed his stutter publicly, and in the midst of political attacks equating his stutter to some sort of proof he's experiencing cognitive decline.

How to help people who stutter

John Hendrickson, author of the recently-released memoir "Life on Delay," has also written about his experience as someone who stutters, including what he knows kids who stutter need from adults.

"Treat them normally," Hendrickson tells TODAY.com. "You don't have to be over-protective and at the same time, obviously, you don't have to be negative — you don't have to be counting every block or repetition or prolongation that your child says. Look them in the eye, be patient, don't finish their sentences and help them build that confidence to communicate."

Hendrickson says he has been in communication with "hundreds of stutterers" for years, adding that "every time I have one of those conversations, I walk away with a slightly different and better perspective on life." Now, his book serves as not only an extension of those perspectives, but another source of accurate representation for anyone who is looking to see themselves in others' stories.

"This is a book I wish I could have read during a more uncertain time of my life," Hendrickson says. "Kids who stutter, kids with disabilities and kids in general are resilient. They are so much stronger than we think they are; they're wiser and they're more observant and better listeners than we ever give them credit for."

Coppen and Short admit that as parents they realize that they don't always have to intervene when their child speaks in potentially awkward social settings.

"You don't want to see your child's feelings hurt, so you have to keep that 'mama bear' or 'daddy bear' thing in check," Coppen, now the event and outreach coordinator for the National Stuttering Association, says. "You're not doing them any favors if you're coming to the rescue all the time."

Short, who the National Stuttering Association Board Chair, agrees, adding that even though her son is in college, "the feeling of being uncomfortable, knowing he's putting himself out there, doesn't go away."

So the proud mom continues to tell herself what she wishes she would have told her former self when her son was first diagnosed:

"'He's going to be OK,' and, 'Don't be so hard on yourself,'" she says. "It's not always going to be easy, but as long as you're there to support your child, love your child, advocate for them and teach them how to advocate for themselves, they'll be fine."

For more information on stuttering, please visit The Stuttering Foundation, The National Stuttering Association or the Ask The Stuttering Foundation YouTube channel.

Related video:

This article was originally published on TODAY.com