These parents fought to legalize CBD in Utah a decade ago. Did it help their epileptic children?

They don’t get together much, these moms and dads whose desperate search for something — anything — that would provide relief to their children with severe forms of epilepsy set them on a course that changed Utah.

The doctor-prescribed medications and special diets didn’t seem to do anything to control the dozens, even hundreds, of often violent seizures their young daughters and sons endured every day.

All of these parents had concluded that the answer might lie in marijuana, the much-maligned hippie culture plant mainstream America had shunned for decades.

Despite being told Utah would never legalize marijuana in any form, not medicinal and certainly not recreational, these mostly conservative, self-described “Molly Mormon” moms persuaded reluctant state lawmakers to let them use cannabidiol, or CBD, to treat their children’s epilepsy.

“People can walk into Maverik and get a case of beer, but I can’t get a nonpsychotropic oil for my kid,” said Jennifer May, one of the group’s leaders. “That just made me so arrrgh.”

What they did in a few short months nearly a decade ago would help pave the way for Utah to legalize medical cannabis, though that was never their goal.

Related

They have stayed in touch over the years, but most of these unlikely advocates hadn’t gathered for a long time.

Their schedules aligned on the rainy first day of spring. They are huddled in a corner of Avenue Bakery in American Fork catching up, crying and laughing on the very day nine years ago that Gov. Gary Herbert signed Charlee’s Law, allowing use of nonintoxicating hemp oil extract from marijuana plants to treat seizures.

They’ve been here for two hours when I arrive. Drink cups and plates of half-eaten sandwiches and cold french fries stretch across the table. April Sintz, Emilie Campbell, Catrina Nelson and Clint Atwater are seated around the table with May. Annette Maughan appears on a laptop screen from her home in Maryland.

Over the next few hours, between soda refills, the story of how it all began and what has happened to their children since will spill out — recollections of triumphant moments and tragic endings. A little more laughter. A lot more tears.

Sintz later shares a video of her son having a prolonged seizure. A seizure is scary to watch. Her son Isaac appears to be shivering as his body stiffens and convulses. He gasps for air. He clutches a soft blanket. His eyes all but disappear into his head. It goes on for several minutes before he seems to emerge from a distant place. He is calm. This was one episode. Imagine it happening over and over and over again.

The CBD oil these parents fought so hard to legalize helped their children to varying degrees. It worked wonders for some. Not so much for others. It never cured any of them. It wasn’t designed to.

“But CBD was a great option for so many,” Maughan said. “Any time you can mitigate the majority of symptoms, you feel like you’ve won the lottery.”

May’s son Stockton, 21, has Dravet syndrome, a rare and severe form of epilepsy with intractable seizures that don’t respond well to medication. He lives at the Utah State Developmental Center. CBD oil didn’t help him.

Campbell’s 16-year-old son Connor also lives at the developmental center. He’s seized from birth. He is cognitively and behaviorally the most acute of any of the kids in this group. He responded well to higher levels of THC, but he can’t have it now that he’s in state care.

Sintz’s son, Isaac, 16, has Dravet syndrome. He lives at home. He has never gone longer than three weeks without a seizure. His kidneys are failing. He’s on a roller coaster but in a good place right now.

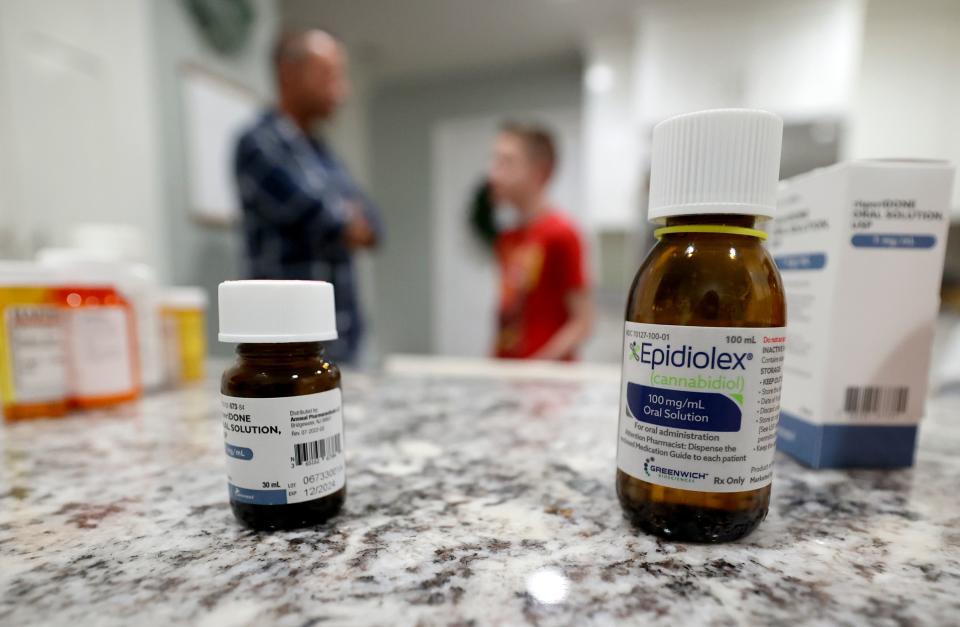

Maughan’s 20-year-old son, affectionately called Bug, also lives at home, which is now Maryland. CBD oil made his seizures worse. Epidiolex, the only FDA-approved treatment for rare forms of epilepsy that includes cannabis, reduced his seizures from 10 a day to less than one. But it caused stomach problems. A CBD patch worked for a while, but his seizures crept back up. He’s trying it again. He was later diagnosed with KBG syndrome, a rare genetic disease. Surgery to release a tethered spinal cord did more than anything to improve his health. He can’t speak or ask for what he wants, but he’s stable now.

“I imagine one day I’ll find out he really hates cheese,” said Maughan, the founder and CEO of the KBG Syndrome Foundation.

Atwater’s daughter, Asia, thrived on CBD oil but died unexpectedly last year. Nelson’s daughter, Charlee, died before getting to try it.

Selling Utah on cannabis oil

Their parents’ mad dash to get CBD oil legalized in Utah started in the summer of 2013. It wasn’t a political or ethical issue for them. It was a medical issue.

Related

Pleasant Grove mom says marijuana compound could help her son

Utah parents look to Colorado for 'life-improving therapy' found in cannabis extract

In July 2013, May started seeing stories out of Colorado, where marijuana is legal, about a cannabis oil that was stopping seizures in children. Dismissive at first, she asked Maughan, then the president of the Epilepsy Association of Utah, what she knew about it. Maughan knew nothing.

A month later, the CNN documentary “Weed” featured 5-year-old Charlotte Figi, who had Dravet syndrome — the same epilepsy as May’s and Sintz’s sons — and intractable seizures.

Her parents found a high-CBD strain of cannabis called “Hippie’s Disappointment,” which contained low THC. Later named “Charlotte’s Web,” the oil stopped her seizures. The story went viral and Charlotte became the face of the medical marijuana movement.

May and some of the other Utah moms considered moving to Colorado to get their hands on what appeared to be a wonder drug. (Charlotte Figi lived nearly seizure free until age 13, when she was hospitalized with COVID-19 symptoms in April 2020. She had a seizure resulting in respiratory failure and cardiac arrest. She died in her mother’s arms.)

Connor Boyack, president of the Lehi-based libertarian think tank Libertas Institute, saw the documentary. He found May through the epilepsy association and posted an interview with her about the need for legal medical cannabis in Utah. Within days, every news outlet in the state did stories about the “Mormon” mom who wanted to legalize marijuana.

On the advice of a former state lawmaker, the group calling itself Hope 4 Children with Epilepsy narrowed its focus to just one treatment: nonpsychotropic CBD oil for epileptic seizures.

Their first meeting with a sitting legislator did not go well. He told them it was never happening, that they were wasting their time. May cried. Campbell swore.

Undeterred, they sat down with lobbyists to map a strategy. They enlisted Laura Warburton as their legislative consultant. Her mantra was “Activists shake fists, advocates shake hands.” So, the moms and dads shook a lot of hands. They mounted a public information campaign and honed their elevator pitches.

“Our legislators kept saying, ‘Well, we don’t want to turn into another Colorado,’” May said.

Some lawmakers told them it would open the door to recreational marijuana. Others suggested they just drive to Colorado to get CBD oil. They took flak from people who said their push for a nonpsychotropic treatment was destroying any chance for a future medical cannabis program.

They told their stories to then GOP state Rep. Gage Froerer. He told them he would be honored to carry the bill. They visited with every lawmaker who would listen. They testified in committee hearings during the 2014 Legislature. They brought brownies to Capitol Hill one day. Store-bought.

Charlee’s law

Warburton found a face for their cause: Charlee Nelson.

Charlee’s mom is at the table at the bakery. A petite woman with delicate features, Catrina Nelson’s 6-year-old daughter didn’t have much time to live. Sadly, Charlee never got the chance to try the oil.

Charlee had her first seizure at age 31⁄2. At first, medication helped control the convulsions, then she started to have horrible falls. She knocked out her front teeth. She had a constant goose egg on the back of her head. She had to wear a helmet.

Catrina and Jeff Nelson watched their little girl decline for nearly two years until doctors diagnosed her with Batten disease, a neurological disorder. Over time, she would suffer 400 to 500 seizures a day and lose her sight, motor skills and cognitive ability.

The Nelsons wheeled Charlee onto the Utah Senate floor in a stroller as senators voted on the bill bearing her name. She was so sedated she didn’t look alive.

Two days later, Charlee and her parents were on the House floor. This time she was sitting up. She loved the standing ovation, smiling as the entire chamber clapped for her. Afterward, her parents wheeled her into the Capitol cafeteria where she nodded off and never woke up. She died two days later.

“She fell asleep as soon as her job was done at the Capitol,” said Catrina Nelson, who has an outline of Charlee’s profile tattooed on the inside of her left arm.

The House and Senate passed the bill. “It was amazing,” Maughan said. “It was the right message delivered by the right people at the right time under the right circumstances.”

Herbert signed it March 20, 2014. The Nelsons attended the bill signing before going to Charlee’s viewing that night. Her funeral was the next day.

“The last week of her life couldn’t have been written better in a book, honestly. The honor that we have in having those memories, the feeling and the love and the community that was supporting us through all of that. They’re my friends now. All of my past friendships have kind of just dwindled away but these are my friends, these are my family now even though we haven’t seen each other forever,” Catrina Nelson said, gesturing to the people seated around her.

Related

The new law caused a run on CBD oil. Manufacturers weren’t prepared for it. Some parents waited months for what they hoped could change the trajectory of their children’s lives. Clint Atwater managed to get some from a friend in California.

He, too, sits at the table in the bakery, the only dad among the moms. His daughter Asia started having grand mal seizures at age 2, sometimes more than 50 a day. She went undiagnosed for seven years as her parents tried a battery of drugs that Atwater believes did more harm than good. At age 9, Asia was diagnosed with 2q23.1 microdeletion syndrome, a rare chromosome disorder.

In August 2013, two of Atwater’s neighbors, one an 85-year-old woman who had seen the CNN documentary, asked him if he had ever considered medical marijuana.

“I just thought fat chance in hell that was ever going to happen in Utah. I thought I’d be willing to try anything at this point because we’d literally had no success with any of the drugs. Some of them caused her to have fits of rage. I didn’t want her on any pharmaceutical drugs,” he said.

A Google search led him to a news story about a Pleasant Grove mom — May — who wanted to be able to legally use a form of marijuana for her then-11-year-old son. Atwater messaged her on Facebook and became an advocate. He had no idea whether CBD oil would work for his daughter.

Asia’s seizures stopped after the first dose.

“For us, it was literally like a miracle,” Atwater said, choking back tears.

Suddenly, the girl who just wanted to stay in bed all day had get up and go. She talked. She played. She rode a tricycle. She went for walks. She learned. She thrived.

Asia didn’t have a single seizure for 71⁄2 years. But last August, she had three “breakthrough” seizures. The consequences can be severe. She died after the third one at age 16.

“For us, it was worth the fight,” Atwater said. “If anything it gave us an extended period of time with her. I’m grateful for it.”

Atwater is the first to leave the bakery. Then Nelson and Sintz. The laptop with Maughan on the screen runs out of battery. May and Campbell linger a little longer.

“We told you way more than you wanted to know,” says Campbell, whose husband Branden is the bassist for the rock band Neon Trees. “It was therapeutic for us.”

But their stories don’t end there.

Related

Life goes on

Parents of children with severe seizures are used to medications failing after a few months or not working at all. They’re constantly trying different remedies, sometimes with initial success. But they’re always waiting for the other shoe to drop.

“We’re faced with the reality, too, that these kids are really not long for this world, and we’re probably going to outlive them,” Maughan said. “You literally grab life by the horns and you just go.”

So, they do the best they can for their children.

I will meet up later with May at the state developmental center in American Fork where Stockton has lived since 2018. She or someone in her family visits him four or five times a week. Visitors aren’t allowed in residents’ rooms right now, so they have to meet in a conference room or outside. This warm spring day, outdoors beckons.

No longer mobile, Stockton spends his days in a wheelchair. May always brings a game in a gift bag because her son likes presents. Today it’s a card-matching game. Stockton ably identifies and matches various animals, then flicks the cards across the long conference room table using his thumb and forefinger. A device implanted under his skin senses abnormal electrical activity in the brain and fires electrical impulses to stop seizures.

May wheels him outside and down an empty street on the campus. He wears a pink and orange tie-dyed polo shirt, pink ball cap and white sunglasses. She stops at an area covered with rocks. In the center is a raised manhole cover. She puts a basket of rocks on Stockton’s wheelchair tray. A lover of basketball, he slowly tosses them one-by-one, pop-a-shot style onto the steel cover 10 feet away. Rock tings on metal. He rarely misses.

At the Campbell house on a recent Sunday afternoon, Connor sits on a drum throne pushing buttons on the washer and dryer. Seeing the spinning clothes through the windowed door mesmerizes him. It’s one of the things he looks forward to on his weekly visit home from the state developmental center where he has lived since last fall. CBD oil with high THC leveled off his grand mal seizures from 10 a day to about one a week.

Evidence of his more fitful times can be seen around the house: holes in the wall, dents in the refrigerator, photos and artwork without frames. Nothing gets broken on this day. But he is constantly on the move: plinking on a full-size keyboard, taking a sip of Diet Coke, listening to a musical toy, taking a bite of noodles. He is sweet and unpredictable. He hugs his mom but pinches her arm at the same time. He is a toddler in a teenage body.

“Connor church” might include a drive to Maverik for a soda or McDonald’s for french fries or to the park. Or a walk inside an actual church well after the congregation has left. The six-hour visit ends with a bath — a bubble bath, thanks to the bottle of dog shampoo Connor dumped into the tub when his mom wasn’t looking. This is how Sundays go in the Campbell home.

The Sintzes also have a routine, of sorts.

April Sintz has dashed off to a midweek youth church meeting, leaving her husband, Kyle, with Isaac and two younger siblings. Isaac has eaten all of his dinner, something he doesn’t always do. He settles on the couch to watch his favorite “Cars” videos. He is Lightning McQueen. He pronounces it “Lo Queen.” Kyle is Mack. April is Sally. He can go from giggly to empty. Isaac smiles and laughs, belly laughs, often on this night.

Before bed, he takes seven medications — four pills and three oils, including Epidiolex, the FDA-approved cannabidiol treatment for Dravet syndrome. Sometimes it takes a minute, sometimes 30 minutes for Kyle to coax Isaac to swallow the medicine. Tonight it goes quickly. Mack helps Lo Queen slip into his “Cars” pajamas, the bottoms several sizes too big for his 75-pound body. Then he holds his son’s arm as they climb upstairs to bed.

They’ll do it again tomorrow. And hope for the best.