My parents spent my 1st Christmas in the hospital. The memory inspired a family tradition

For many, Christmas Eve might sound like carols on the stereo, a fire crackling merrily under a row of stockings; the clink of glasses and cutlery as friends and family gather round the table to share a holiday meal.

It might sound like church bells at a candlelight service, or the enveloping stillness of a quiet, snowy night. To others, it might sound like the pleas of children eager to stay awake just a little bit longer, hoping to catch a glimpse of the man in the big red hat.

But for my family, Christmas Eve sounds like a hospital.

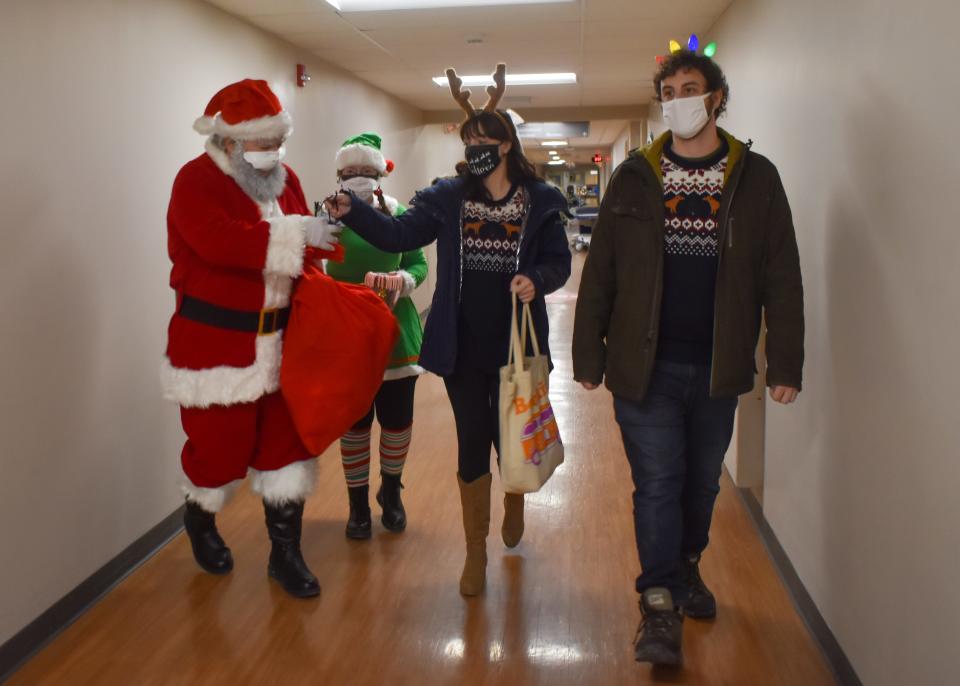

The brisk whoosh of sliding doors opening into a fluorescent-lit waiting room; the low groan of passing gurneys on a waxed tile floor and the impertinent beeping of any number of monitors and machines — this is the soundtrack to our annual visit to all three Broome County hospitals on Christmas Eve.

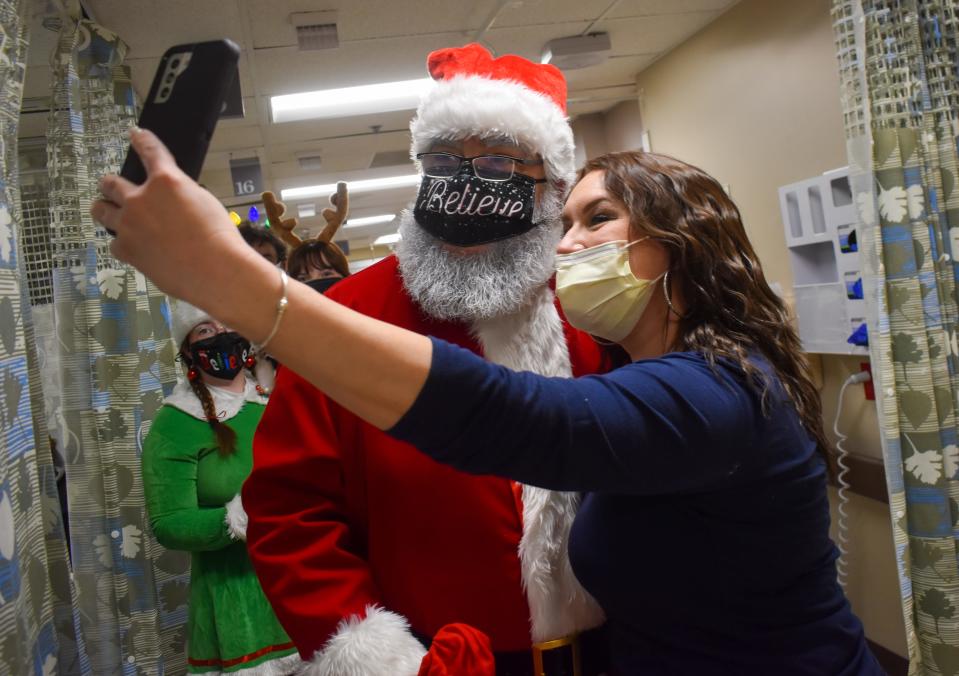

At the center of it is my father, dressed in red from head to toe. His bushy silver beard has been combed out to its fullest volume and enhanced with streaks of white, though less styling is needed with each passing year.

He strides the hallways with a hearty “ho ho ho!”, yet enters each room softly enough so as not to startle the family inside; a knowing twinkle in his eye as he produces a teddy bear from the depths of his velvet sack.

In another life, my dad could have been a voice actor.

In this life, he is many things: father of three, husband to my one and only mother, Wendi; “Uncle Todd” to a small army of godchildren.

He has been “Coach Todd” to generations of softball teams, and “Mr. Todd” to the dozens of kids that passed through our church’s youth group.

'Spreading light':Jewish leaders turn to message of Hanukkah to fight antisemitism

Oakdale Commons is transforming:What we know, don't know about Johnson City development

Trail of Truth:Binghamton group draws national attention to overdose deaths

He’s the guy that ran the Endicott soup kitchen twice a month for 10 years; the one that served “anything but soup.” He’s the one standing along Main Street every Ash Wednesday in his sweeping white elb, offering a cheerful blessing and “ashes to go.”

Monday through Friday, he’s “H. Todd,” the one in charge at his state job. (Fun fact: my sisters and I all have a silent “H” in our names in a nod to his mysterious first name).

On the weekends, he’s sometimes “Deacon Todd,” ministering to a handful of Lutheran congregations in Norwich, Oneonta, Cooperstown, Elmira and beyond.

But on this, the holiest night of the year, he gets to be Santa Claus.

How one Santa inspired another

My father didn’t come to be Santa by accident. He didn’t spook the Big Guy off our roof and take his place by donning the coat of legend. He wasn’t taken in as an infant and raised by a family of toymaker elves, nor was he visited by three spirits in the night — at least, not that he’s ever let on.

My dad was inspired to step into the suit by another Santa, a mysterious benefactor who made a moment of fear and worry just a bit better for him and my mother when they were sitting in a hospital room 27 years ago.

They never saw that Santa’s face. He might not have even worn the suit, for all we know.

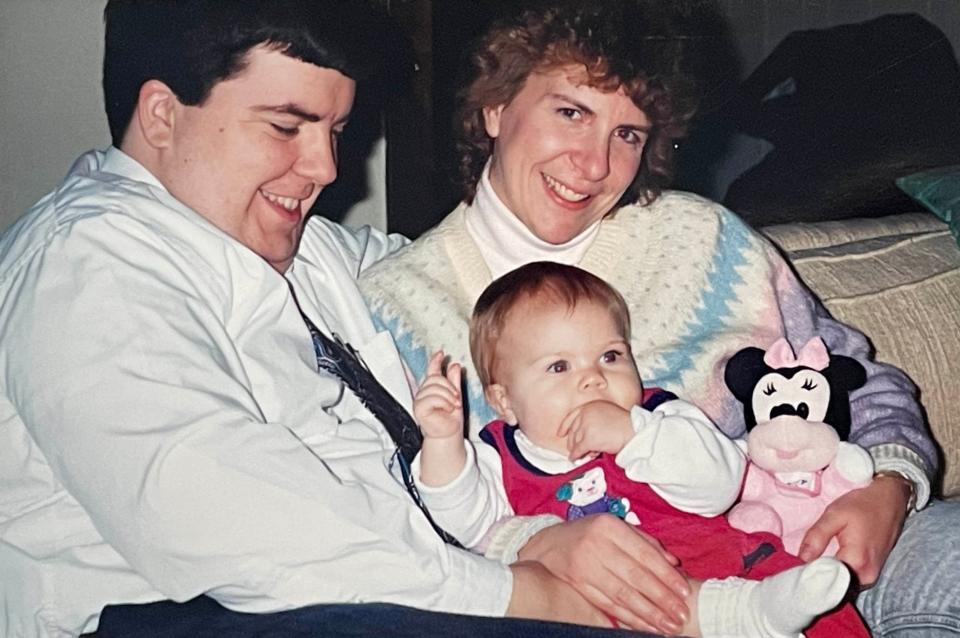

What we do know is that I spent my first Christmas in the hospital, with a 103-degree fever. I had just come home a few days before from another extended stay at a different hospital, this time as I was recovering from a fractured skull.

I was nine months old in December 1995, toddling around the kitchen in my walker. On the few occasions I permitted my parents to put me down, I had to be kept busy. My parents were always careful to keep the cellar door closed, but for one instant it wasn’t, and down the stairs I went.

“Awful,” my mom recalls feeling on that fateful day, a pained look tightening her features. “Devastated. I was so afraid I was going to get to the bottom of the stairs and find you in a million pieces.”

My father, she said, ripped the railing right off the wall in his rush to reach me.

My parents were 27 years old at the time, the same age I am now. It isn’t easy to try to imagine the fear and dread they must have felt, but every year, I see it on the faces of the parents we encounter in the hospitals, sitting worriedly at their child’s bedside, or rocking a sick and fussing baby.

I’m reminded of all the other Christmases I can remember; all the childlike joy and warm wonder I was so fortunate to experience.

Growing up means realizing that all that Christmas magic is a testament to my parents’ love and devotion to my sisters and me. Who else would go to such great lengths — building a makeshift fireplace the years we didn’t have a chimney, tracing reindeer prints in the snow as irrefutable proof of a certain nighttime visitor — to ensure that magic would endure?

The true magic of the holidays — indeed, in life — I’ve learned, is love.

On that Christmas Eve 27 years ago, a nurse came in with a single gift: a baby doll. A man whose name we’ll never know had delivered a batch of toys to the pediatric unit at Wilson Hospital.

“I’d never given much thought to the kids in the hospital on Christmas,” my dad said. “I liked the idea, but I thought it should be Santa bringing the toys.”

In hospital holiday tradition, 'We are all Santa'

And so, for the next few years, it was. My dad would change into a borrowed Santa suit in our garage, careful so as not to appear before the wondering eyes of my sister, Kayleigh, and me.

Our church took up a collection to buy the toys he would deliver to the three area hospitals and off he would go, year after year, until Kayleigh and I were old enough to notice his Christmas Eve absence.

The tradition remained on hiatus through the birth of my youngest sister, Meghan, in 2003. It was not long after that I learned the secret of Santa myself.

You’ll never hear in my house that Santa Claus doesn’t exist. As my parents gently explained to a very tearful 10-year-old, we are all Santa — that’s the true magic in it.

As many burdens may accompany being the oldest daughter, the job is not without its perks: staying up late on Christmas Eve, giddily helping my parents arrange gifts under the tree, stuffing the stockings, taking a gratuitous nibble from the cookies left by the fireplace. To me, this feeling was better than opening any gift on Christmas morning.

And so it was natural for me to accompany my dad when he resumed his sleigh-driving tradition six years ago. Both my sisters come, too — Meghan in an elf outfit, handing out candy canes to the nurses, and Kayleigh in reindeer antlers, holding doors and leading the way to the pediatric unit.

I trail behind with my camera, as ever, but I have my own job, too — one only I can do.

“It’s going to be OK,” I say to the parents in the throes of their own worst fears, with an assurance belonging to one who made it out. “Merry Christmas.”

How to help

Besides the handful of hospital-bound children we encounter, the Southern Tier community is home to many others whose holidays could stand to be merrier.

For the past four years, several local organizations have facilitated a holiday toy drive to benefit families impacted by mass incarceration. Broome County has the second-highest incarceration rate per capita in New York state, leaving many children and families without their loved ones — this year alone, more than 500 toys were distributed to 150 families.

The Stakeholders of Broome County deploys a street outreach team on weekly excursions to check in on and deliver food and supplies to Binghamton’s unhoused residents. The need is greatest during the coldest months.

Monetary donations can be made at Cash.me/$StakeholdersBC.

The following items can also be purchased from an Amazon Wishlist or dropped off at Garage Taco Bar, 211 Washington St., Binghamton, NY 13901:

Drawstring bags

Backpacks

Insulated socks

Underwear (regular and thermal)

Hooded sweatshirts

Sleeping bags

Blankets

Gloves & hats

Bus passes

Gift cards

Hand/feet warmers

Ponchos

Menstrual products

Tarps & umbrellas

Canned food with pop tops

Snacks and bottled water

This article originally appeared on Binghamton Press & Sun-Bulletin: Being Santa: How Christmas in the hospital became a family tradition