Parents who want to challenge a library book in a Wake school may face new time limits

Wake County could limit how often parents can file challenges to get books removed from schools.

School administrators unveiled this week proposed policy changes, including that decisions made on book challenges would be binding for two years. Officials say a two-year delay before the same book could be challenged again reflects how much time is spent hearing each individual challenge.

“It’s just balancing frankly the time commitment involved in putting together the committee at that school,” said school board attorney Jonathan Blumberg. “People are very busy already. They have to stop, they have to read the whole book, go through the whole standard and so forth and make a decision.”

Parents have filed five book challenges in Wake since 2021. All the challenges were rejected.

No decision was made on adding the two-year limit. School board members said they need more time to consider the issue.

Books on race and sexuality often targeted

Wake, like districts across the nation, has become part of the national school culture war over what books should be allowed in schools.

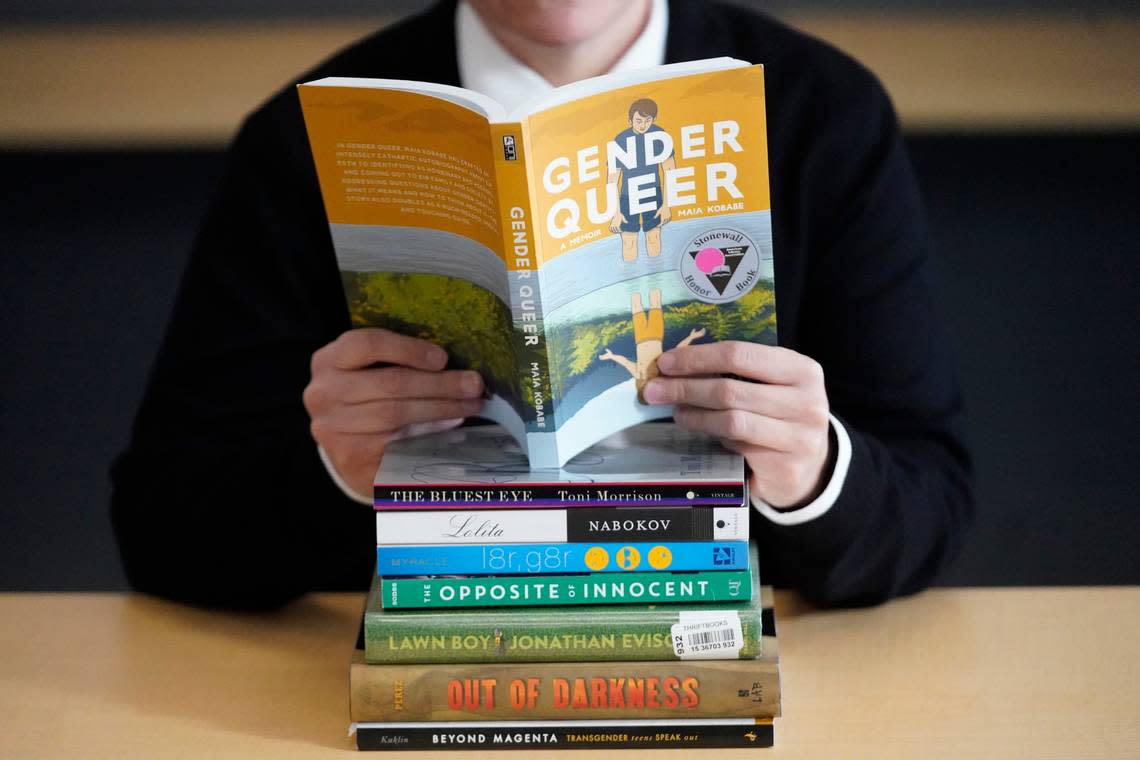

Over the past two years, people have brought at least 189 book challenges across North Carolina’s 115 public school districts, journalists from nine state newsrooms learned by surveying the districts as part of Sunshine Week. Books on race and sexuality were among the most targeted.

In December 2021, a group of parents and community activists filed criminal complaints accusing the Wake County school system of violating obscenity laws based on some of the books in school libraries. But Wake County District Attorney Lorrin Freeman announced she would not file criminal charges.

Speakers now regularly show up at Wake school board meetings reading excerpts from books that they say should be removed from schools due to their sexual content and language.

At last week’s Wake school board meeting, speakers questioned books such as “Jack of Hearts (and other parts),” whose main character is a queer high school student who writes a sex advice column.

The Rev. John Amanchukwu said “Jack of Hearts” is in six Wake schools. He read excerpts from the book that talk about anal sex and oral sex.

“The question is who is the pervert who is allowing this to be purchased and delivered to our libraries?” Amanchukwu said. “Come out, come from wherever you are. Who is the pervert that signs off on this filth?”

“Jack of Hearts” has been challenged across the nation, leading author Lev Rosen to issue a statement defending the young adult novel.

“As I said, we all want what’s best for these kids,” Rosen said in the statement. “But parents who don’t want teens to see queer teenagers in books taking control of their sexuality, who don’t want any teenagers to take control of their sexuality — they’re trying to put the cork in a bottle that shattered years ago.“

Some people, such as school librarians, have spoken at board meetings about providing students with a diverse library collection.

What is ‘pervasively vulgar?’

School officials said the updates to the book challenge policy are meant to provide transparency and clarity about how the process works. For instance,the policy says groups reviewing book challenges are required to read the entire book and not just individual passages.

Currently, Wake’s policy says books and other instructional materials may be removed from the school library collection “only for legitimate educational reasons.” But the updated policy says material can be removed if it’s “educationally unsuitable, pervasively vulgar, or inappropriate to the age, maturity, or grade level of the students.”

The new wording is taken from state law on book challenges, according to Blumberg, the board attorney.

“There is not any sort of elaboration in the law on pervasively vulgar,” Blumberg said. “I mean it’s basically repeated vulgarity throughout a material.”

The new policy also strengthens the role of a district-level committee that currently makes recommendations on book challenges. Now the decisions of the Central Instructional Materials Committee will be final unless they’re appealed to the school board.

The Central Instructional Materials Committee will also be the starting point to hear all challenges to “core instructional materials.” This is material used across the district in classrooms to teach state instructional standards.

Is two years too long?

There was extended discussion during a school board policy committee meeting about making decisions on challenges binding for two years.

During that two-year window, Marlo Gaddis, Wake’s chief technology officer, said parents who don’t want their children to read a particular book can still be accommodated to read something else.

In addition, Gaddis said that even without a formal book challenge that schools can remove materials on their own.

“If there are a dozen parents coming forward, I don’t believe they would even need a grievance process,” said school board member Monika Johnson-Hostler, chair of the policy committee. “I think they would make an internal decision at the school.”

But school board members Cheryl Caulfield and Dr. Wing Ng said they’d want the proposed two-year period lowered.

“If it’s a problematic book, it needs to be addressed,” Caulfield said. “I don’t like limiting it just because somebody decided.”

But some other board members said they’d be fine with two years. In addition, the board could waive the two-year rule at any time.

“I felt that two years was very generous and deferential to families,” said school board chair Lindsay Mahaffey. “Having seen this process and what goes into it, from the school level all the way up to the board level ... I would have thought it would have started at three years.”

School board members Lynn Edmonds and Sam Hershey warned that unless they have time limits they could be bombarded by groups constantly challenging the same books.

“I really wouldn’t support anything less than two years,” Edmonds said. “You really could have an orchestrated situation where somebody brings the same book every Monday for six months.”