Paris after dark: Brassaï at the Museum of Fine Arts

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Famed Hungarian-French photographer Brassaï was one of a number of photographers who made his name and reputation in the inspiring artistic milieu of Paris between the two world wars.

His evocative, iconic photographs of night-time Paris during the 1930s and 40s are on view at the Washington County Museum of Fine Arts through Jan. 30.

Brassaï’s photographs feature a host of colorful characters from the streets, dancehalls, bars, and theaters of after-hours Paris, together forming a vision of Paris both glamorous and gritty, at once sensual, romantic and edgy.

After attending art school in Berlin, Brassaï moved to Paris in 1924, where he worked for much of his career. Born Gyula Halász in 1899, he adopted the name Brassaï from his birthplace, Brasso, a Romanian town (formerly Hungarian) in Transylvania.

A sculptor and painter by training, he learned the technical aspects of photography from fellow Hungarian artist André Kertész (1894–1985), but the two artists’ subject matter could not have been more different.

In contrast to Kertész’s cool compositions and meticulous still life, Brassaï focused on Paris’s nocturnal life and racy bohemian culture, aspects of society he explored in depth — sometimes alone, at other times accompanied by friends like writers Henry Miller (1891–1980) and Jacques Prévert (1900–1977). Brassaï was attracted to aspects of Parisian nightlife that others neither experienced nor depicted.

"Drawn by the beauty of evil, the magic of the lower depths, having taken pictures for my ‘voyage to the end of night’ from the outside, I wanted to know what went on inside, behind the walls, behind the façades, in the wings: bars, dives, night clubs, one-night hotels, bordellos, opium dens," he said.

Alongside his artistic practice, Brassaï earned a living taking commercial photographs and writing for magazines such as Harper’s Bazaar, Minotaure, Verve, Coronet and Picture Post.

Themes

His 41 photographs take you on an atmospheric visit to Paris in the 1930s — into hotels, bars, theaters and artist studios. Brassaï’s famous ability to capture the night is shown off in street scenes featuring the gangsters, prostitutes, wanderers and cesspool workers who were part of the city’s life after dark.

The exhibition is installed thematically. Sections are devoted to “Nightscapes,” Brassaï’s characteristic romantic depictions of Parisian landmarks; “Nightlife,” featuring images of theater, dancehalls and couples at bars; “Suzy’s,” a series of images taken inside a well-known Parisian brothel; and “Transmutations,” experimental photographs made with the cliché-verre technique — a hybrid form of photography and etching in which Brassaï scratched imagery onto an existing photographic glass-plate negative before printing. This experimental technique was developed in collaboration with Brassaï’s close friend, Spanish artist Pablo Picasso (1881–1973).

Exhibition highlights

The exhibition include Brassaï’s powerful series of eight photographs, “A man dies in the street, Boulevard de la Glacière, from 1932. This sequence of photographs illustrates the artist’s startling and unprecedented work in the new field of photojournalism.

Don't miss: Piecing together War & Pieces: Reflection on conquest and consumption arrives at WCMFA

Shop early: Locally made gifts more than an alternative to supply-chain-stymied items

These images were taken from the window of a distant building and show the events unfolding with a chilling objectivity. In the first work, the man lies dead on a mostly empty street. In the next set of images, strangers begin to form a crowd around him and the man is taken away. In the last image he disappears and the street is empty again.

The photographs form a memento mori, reminding us of the fleeting nature of life and, perhaps also, the ways in which we push death from our minds to keep living. In the final photo, there is no indication of the drama that had transpired moments before. The life of the city and the majority of its inhabitants continues uninterrupted.

A man dies in the street, Boulevard de la Glacière was first published in the Revue Labyrinthe, a Paris-based interdisciplinary and scientific journal that often published on literary and philosophical subjects.

Perhaps the most recognizable image in the exhibition is Brassaï’s iconic view Paris from Notre Dame, ca. 1933, which brings us high above the city to the level of the Le Stryge (the vampire) Notre Dame’s most famous gargoyle.

In this emblematic, atmospheric nocturnal view. Brassaï gives the creature a contemplative, enigmatic appearance. Le Stryge, although today indelibly associated with Notre Dame, was actually added to the cathedral in the mid-19th century during a large-scale restoration driven in part by Victor Hugo’s immensely popular novel, The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1831).

Le Stryge and other gargoyles were designed by Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, the architect in charge of the architectural and decorative renovation. Le Stryge serves as a nice reminder of the enduring power of Notre Dame and its changes over time. About 100 years after this sculpture was added to the roofline, Brassaï convinced the cathedral's caretaker give him access to the roof, where he captured this remarkable shot.

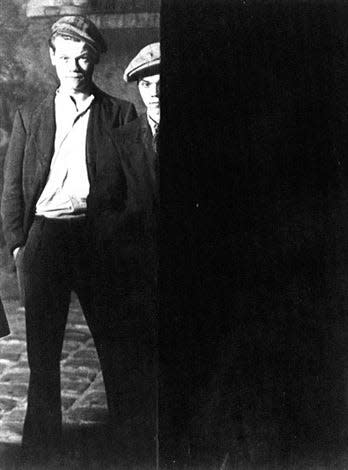

Brassaï, however, is perhaps best known for the characters he rubbed elbows with — the types of people most of us avoid if we, by chance, are out in an urban area at night. Street toughs from Grand Albert's gang, near the Place d’Italie, ca. 1931 is a dramatically bifurcated composition that seems to portray an imposing wall filling half the picture plane. The wall is, in fact, created through darkroom manipulation; the negative shows there is no actual wall, just a blank expanse of photographic paper that Brassaï has expose) for ominous effect.

"Although I succeeded in taking photographs of these toughs, one day they managed to lift my wallet, even though I had already paid them handsomely for their favors," he recalled. "I didn’t lodge a complaint, however. Thievery for them, photographs for me. What they did was in character. To each his own."

It is to Brassaï’s “to each his own” attitude, perhaps, that we owe the power of his pictures. He presents his subjects with dignity and individuality intact, free from implied judgement or moralizing. We may occasionally feel that the Paris we see, so atmospherically foggy, is a film set for a drama. But Brassaï’s faces tell us otherwise. These are real people; although they are knowingly posing (a bit like actors), they are reaching out to us from nearly a century ago, inviting us to into their world.

This article originally appeared on The Herald-Mail: Parisian secrets: Brassaï at the MFA