'Our park': For 100 years, this Olmsted park fostered generations of Black Louisvillians

One hundred years ago, most parks for Black people in Louisville lacked swings, slides and even drinking fountains.

Of the now 13,000 acres of parks that exist in Louisville, during segregation, Black people only had access to 145 acres.

About half of that belonged to Chickasaw Park.

When The Olmsted Firm began working on plans for the west Louisville park on Southwestern Parkway in 1923, it wasn't ideal by any means. The 61 idyllic acres neighbored a hostile white neighborhood and the Louisville Leader, a weekly paper for the Black community, called the whole area "an unfit plot of ground far out of the way."

Former metro councilwoman Cheri Bryant Hamilton saw things differently. When she was a young girl in the neighborhood in 1956, Chickasaw Park had water fountains, tennis courts, slides, swings and a wading pool — things other Black parks in the area didn't have.

She has fond memories of the concerts and festivals held there and remembers the times she and her sister enjoyed pony rides in the park.

"We felt like this was a country club," Hamilton said.

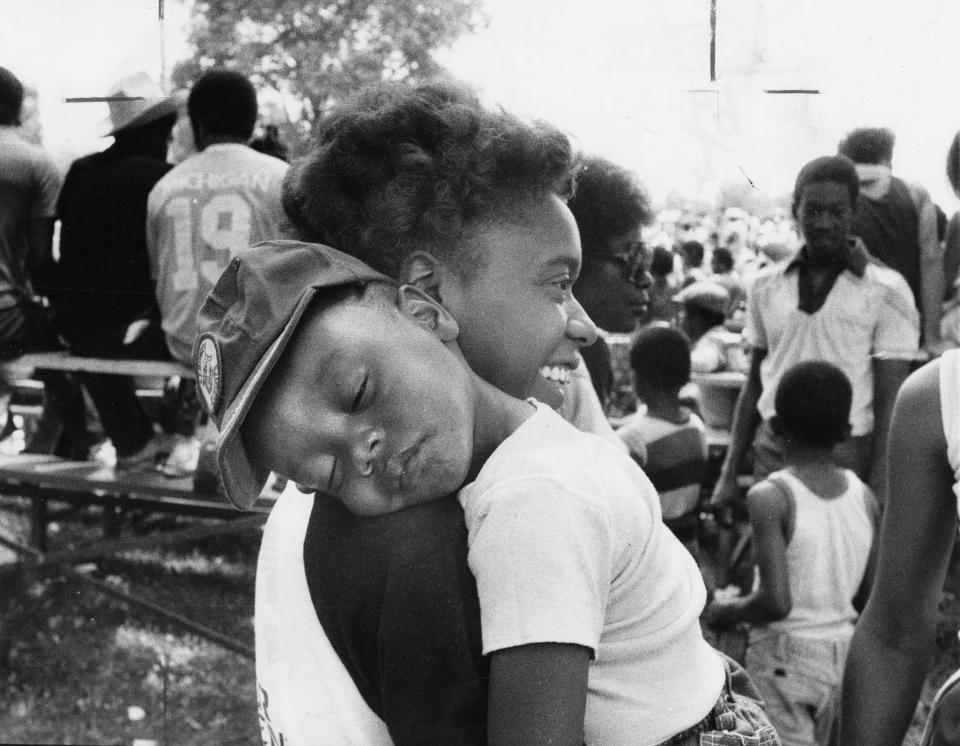

Black families often gathered at the park — teenagers cruised through it and children played there. Hamilton, like so many other Black Louisvillians, grew up at Chickasaw Park and alongside its sister organization, the West Louisville Tennis Club.

A century later, the history of the neighborhood and that park are just as rooted to that land as the Ohio River that runs alongside it.

"It was a special place," Hamilton said. "It was 'our place.'"

Today, Chickasaw Park is most widely known as a place where Muhammad Ali, a Louisville native, used to train. Anyone who's lived in the neighborhood long enough likely has a story about seeing The Greatest run through it. Some even remember him wearing his 1960 Olympic gold medal while working out on the grounds.

Hamilton, who is part of a group researching the history of the Chickasaw neighborhood for a book, has a clear memory of sitting on the front porch with her father and watching him run past her house.

You may like:How working for a major airline led to this Louisville gym's one-on-one focus

But all that history needs to be maintained and improvements are desperately needed to keep Chickasaw Park viable for the next 100 years, said Layla George, executive director of the Olmsted Parks Conservancy.

"I think that we have fallen behind our peer cities, significantly, when it comes to park investment and park maintenance," George said. "Really, this park is 100 years old. That's a lot of maintenance and deferred maintenance, and it's a real problem with our public park system."

In the past few years, help has trickled in. Federal and city funding, donors, grants and local partners have come together to give Chickasaw Park a $4 million facelift. Plans are in the works to install new windows and a roof at the lodge. Improvements are underway at the pond, and eventually, a butterfly and bee garden will be planted to honor the legacy of Muhammad Ali.

Wilderness Louisville, a nonprofit that works to promote the development, stewardship, and community awareness of public spaces in Jefferson County, is currently clearing land to install a new playground.

The only Olmsted park built for people of color

When The Olmsted Firm designed Chickasaw Park in 1923, it wasn't the serene views of the Ohio River or even the treasured public clay tennis courts that set it apart from the 700 parks in the company's world-renowned portfolio.

It was the people who would use it.

The West End park is believed to be the only park the firm ever designed in the United States specifically for Black people during segregation. Why exactly that is, is somewhat left to speculation, said Patrick Lewis, the director of collections and research at The Filson Historical Society.

More:'When you behave you die young.' Louisville centenarian shares her secrets to life, success

The park was built in the first Great Migration, Lewis said, when many Black southerners relocated to Midwestern and northern cities. As soldiers went off to fight in World War I, it left a major hole in the workforce. These industrial jobs created an opportunity for many Black families, eager to escape oppression in the South.

Segregation didn't officially take hold in Louisville until the 1920s, but tensions rose throughout Louisville in the late 19th and 20th centuries. In 1911, the West End Improvement Club requested that Black people be banned from Shawnee Park, 4501 W. Broadway, according to a report from the Olmsted Parks Conservancy about Chickasaw Park's history.

The parks board denied the initial request, but two years later, Shawnee Park had a playground for "colored fellow citizens." Similar designations followed in Cherokee and Iroquois parks, and by 1921, signs marking off spaces for Black parkgoers were a common sight in Louisville. Tensions mounted that year when the pastor of Quinn Chapel AME Baptist Church was kicked out of Cherokee Park for not using the segregated area, according to the Olmsted report.

Later that year, the Riverview Farm was purchased for $81,000 with the intention of turning it into a park for Black Louisvillians, according to the Olmsted report. Feelings were mixed, though. Local Black leaders thought accepting a park of their own meant they were agreeing to segregation.

Amid growing controversy, the parks board contracted with the Olmsted Brothers Landscape Architecture to provide a preliminary plan for the park improvements in December 1923. In its earliest days of operation, Chickasaw Park had two tennis courts, two baseball diamonds, and one football field.

But funding fell short of the Olmsted firm's vision, and it took until the 1930s to complete the project. The original lodge was built in 1929, and walking paths followed in 1931. Construction on the lake, where many local children learned to fish, was completed in 1936, which gave the Black community a place to canoe in the summer and ice skate in the winter. More slides, swings and a croquet court were added in the 1940s.

You may also like:The traffic signal and corded bed: 8 Black inventors you didn't know were from Kentucky

Park use increased dramatically in the late 1940s and early 1950s, following a lawsuit that allowed Black people to move into the neighborhood across the street from the park.

Louisville Parks didn't officially integrate until 1955, but by that point, Chickasaw Park had become a hub for the community for family picnics and weekend outings.

"I think the park means a lot to the Black community of today," said Aretha Fuqua, who lives in the area. "In 1923, that was the [only] park we could go to, so it's like the city of Louisville handed us a lemon and we've taken that lemon and made lemonade. And that's the test of greatness of it all."

'A good attitude and a willingness to learn'

It's difficult to separate the park's legacy and its milestone 100th birthday without talking about an organization that has grown and evolved alongside it.

Chickasaw Park has a "twin" in the West Louisville Tennis Club, which was also founded in 1923. The organization is based out of the 12 courts in Chickasaw Park and for the past century, children and adults alike have come to the park to learn the game of tennis.

When Fuqua first biked over to the park in her mid-20s, she had just returned home to Louisville from college. She'd played basketball at the college level, and she didn't have any experience with tennis. But the man who was running the program at the time gave her a racket and his undivided attention.

That changed her life, she said, and over the years, that same type of encouragement has changed so many others, too. Now she's the president of the club, and the organization has persisted over the years as a focal point for the community.

The club doesn't charge families to learn the game. All you need is a good attitude and a willingness to learn. Clinics run throughout the summer, but there are also adults in the neighborhood who teach kids the game from just after the Kentucky Derby season until temperatures drop to below 30 degrees and it's too cold for the ball to bounce.

Six of the 12 tennis courts where the club plays are clay, and they’re considered a national treasure ― they’re the only public clay courts in the country.

Sharonda Holmes, who participated in the club as a teenager in the 1980s, said the organization and Chickasaw Park gave her the foundation for who she is today.

More:This Louisville father manages some of music's biggest acts, including Bailey Zimmerman

The life skills she picked up in the park were invaluable, she said. There were subtle lessons, such as honesty, in learning to call the lines in the game correctly, and larger ones like how to stand up for yourself in a productive way, when someone made a call with which she didn’t agree.

"Things that I learned at Chickasaw Park have carried me through life," she said.

Chickasaw Park is 'its own little city'

The neighborhood and the tennis club do what they can to keep the park clean, Fuqua said, and they pitch in each year to help reset the clay on the tennis courts. Someday she’d like to convert two of the tennis courts into pickleball courts. In a perfect world, the park would have indoor courts, she said, so that the club can serve the neighborhood’s young people year-round.

Fuqua says the park is made up of two kinds of people ― "park people" and "tennis club people."

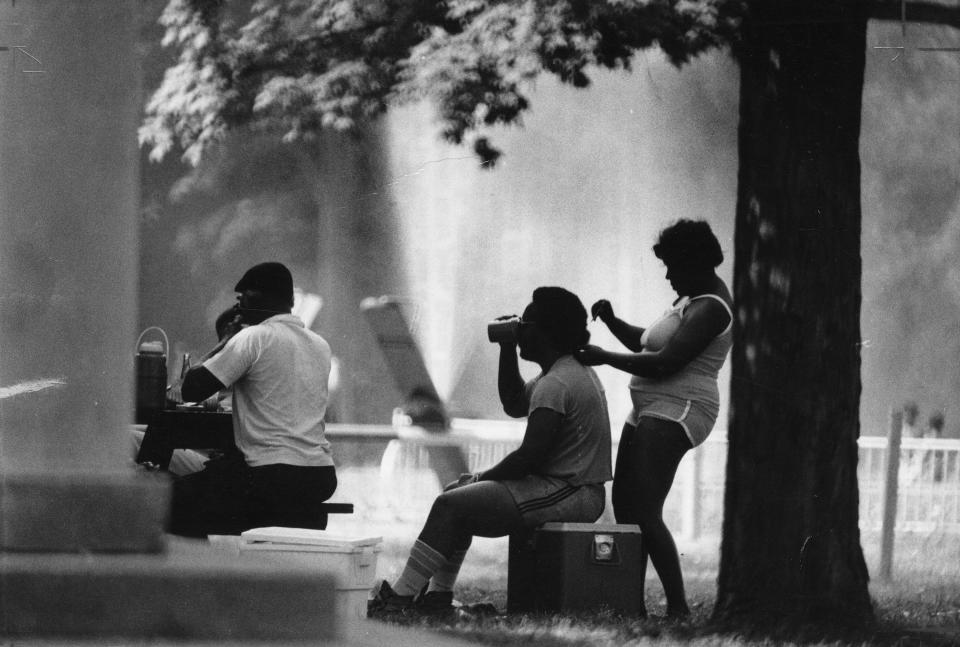

Today, the park operates like its own little city. It doesn't really matter how cold it is, Fuqua said, as long as the sun is shining, the park is active. Groups of teenagers hang out in the parking lot and listen to music. Elderly people play dominos or chess. Walkers and runners use the same loop Muhammad Ali trained on day after day. The basketball courts stay busy and the aging group of gentlemen, who tell "old fishing stories," is robust.

"If you ride through that park, there's a section for every kind of people that would come through," Fuqua said.

Chickasaw Park has come a long way from an "unfit plot of ground far out of the way," as the old newspaper once said. Now Fuqua believes "it serves the community in the truest sense of the word."

One hundred years ago that project was "a lemon," as she put it.

A century later that's not the case at all.

For Fuqua, Hamilton, and so many others, it has been and always will be "our park."

Features columnist Maggie Menderski writes about what makes Louisville, Southern Indiana and Kentucky unique, wonderful, and occasionally, a little weird. If you've got something in your family, your town or even your closet that fits that description — she wants to hear from you. Say hello at mmenderski@courier-journal.com or 502-582-4053.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Chickasaw Park is only Olmsted Park designed for Black Louisvillians