Part 2: As a teen, Sarah 'Cindy' White set 1975 fire that killed 6. 'It won’t ever be OK.'

This is the conclusion of an exclusive IndyStar story about Sarah "Cindy" White, who was convicted of murder as an 18-year-old in 1976 for setting a fire that killed a Greenwood family. Now 66, White has been held at the Indiana Women's Prison longer than any other women incarcerated there as supporters fight for her release. Read Part 1 here.

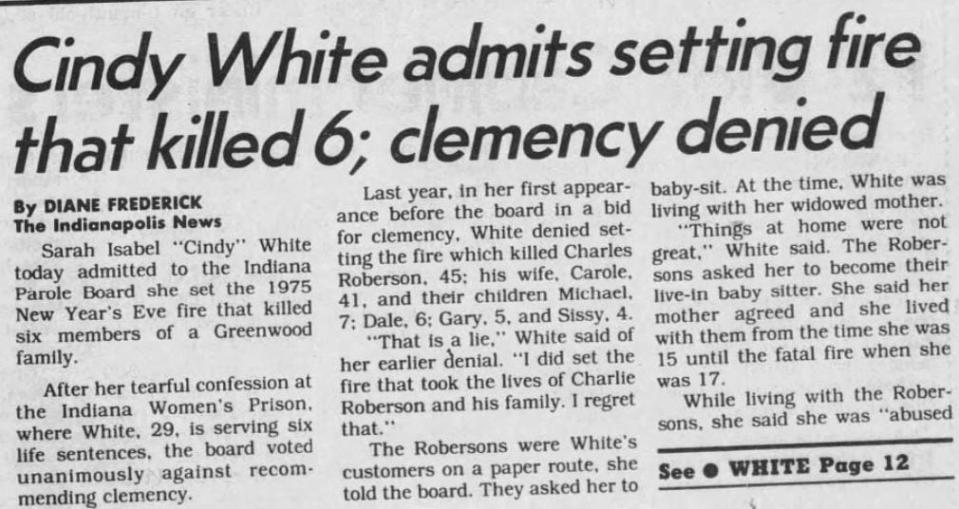

The investigation into the Dec. 31, 1975, fire that killed six members of a Greenwood family moved quickly as officials zeroed in on a suspect: Sarah "Cindy" White, the family's live-in babysitter — and the only person to escape the New Year's Eve inferno.

A Johnson County grand jury indicted 18-year-old White on March 5, 1976, and the teen was charged with six counts of murder and one count of felony arson.

At her trial, which began the following month, prosecutors portrayed White as a jilted lover out for revenge against the Robersons. They used the love letters she and Charles Roberson had exchanged and nude photographs found in his wallet to build a case against White. They also elicited testimony that White had asked her sister-in-law about a fire that damaged her grandmother’s house days earlier, including how it started.

Investigators testified about finding a half-empty gas can near the garage door. They talked about discovering "burn patterns" and "alligator charring" ― concepts that decades later would be challenged as reliable evidence of arson.

White took the stand and denied setting the fire. It was a claim she clung to until 1987.

On May 10, 1976, a jury convicted White of all charges. Less than two weeks later, a judge imposed six life sentences. At that time, life imprisonment was the mandatory punishment in murder cases. Today, the maximum punishment for murder in Indiana is 65 years.

The 18-year-old became inmate No. 0394 at the Indiana Women’s Prison, then located in the middle of a residential neighborhood on the eastside of Indianapolis. She was placed in an intake room with a bed, a chair, a table and a covered pot to use as a toilet.

Staffers at that time remembered White as an immature and scared teenager suddenly thrust inside an adult, maximum-security prison. They recalled her as someone who didn't have visitors.

White said she avoided speaking about her troubled past. Instead, she engaged in self-destructive behavior and was prone to "habitual self-mutilation" and suicidal episodes. Dr. Paul Shriver, then a staff psychologist for the Indiana Department of Correction, later wrote in a report that grief over the Robersons' deaths and guilt for her role in them drove White into deep depression.

"She had survived by denial," said Charlie Asher, an attorney who has been working on White's case since the 1990s in an effort to free her. It was a lesson, he said, she had learned as an abused child: "The world was not a place where she could talk."

Aha! moment: ‘You mean, I’m not alone?’

White had been in prison for about a decade when she penned the hardest letter she'd ever written. It was addressed to her dead father.

She told him she'd always wanted to be a daddy's girl. Then she asked for the answer she'd never hear: "Why would you hurt me like this?"

White also wrote to the other relative she said abused her. The message was straightforward: "I hope you burn in hell for what you did."

She wrote to her dead mother, too: "If I caused you to be drunk … I'm sorry. But you were supposed to protect me, and you didn't, but I love you anyhow."

The letters marked a turning point that began when White joined a counseling group for incest survivors. Reluctantly, she attended her first session. And then another, and another. The letters were an exercise to help White recognize the abuse she endured was not her fault.

At those sessions, she saw familiar faces who shared familiar stories of abuse from their fathers, grandfathers, stepfathers, brothers, uncles, stepmothers, sisters. Even her counselor shared her own story of being abused. One after another, the women talked about how they were forced to stay quiet and why they swore to never tell anyone. And finally, after several years, it dawned on White.

"You mean, I'm not alone?" she realized. "This happened to someone else? This is not just something that happened to me?"

Former FBI profiler: 'A picture of truthfulness'

By the 1990s, White had admitted her role in the fire and spoken openly about her past, including her sexual abuse allegations against the Robersons. She'd lost all her appeals, and the Indiana Parole Board had repeatedly denied her petitions for clemency.

But she continued to garner some passionate allies.

One of them was Asher, her attorney. He described White as "one of the most courageous and deserving" clients he's represented. Central to his efforts to win White’s freedom is the traumatic backstory the jurors who convicted her never heard.

They knew about the love letters and the nude photographs, but not the coercion Asher said White suffered. They knew of her psychiatric problems, but not the decade-long childhood abuse that caused them. And they didn't know what research has since revealed about the impact of abuse on children's brain development and function, including impulse control.

"Here’s a system that convicted someone it didn’t know in the slightest," Asher said. "If you want to spread around fault, there’s tons here."

For one, the institutions and experts ― the doctors at LaRue Carter and her defense attorney at trial ― should have tried to find out about the troubled teenager’s history of abuse, Asher said, but they failed to do so.

Inside 'bizarre' Delphi murders case: Evidence leak, suicide, Odinists and legal chaos

"It’s a catastrophically overlooked issue in criminal cases," he said. "What was the defendant’s life? What was going on? What had happened to them?"

Asher also pointed to Indiana’s harsh sentencing laws. In the 1970s, Indiana required life imprisonment for murder convictions, even in cases like White's, in which prosecutors neither alleged nor proved she intended to kill the Robersons.

"Nobody gets voted out of the legislature for being too draconian with the criminal code or with our sentencing scheme," he said. "They get elected for that."

Candice DeLong, a former FBI agent who took an interest in White's case, remembered first hearing about "some crazy teenager who set a house on fire and killed six people" when she was a psychiatric nurse at Northwestern University in 1976.

Nearly 40 years later, after retiring from a second career as an FBI criminal profiler, DeLong met that teenager. She featured White on her documentary series, "Deadly Women."

"I've interviewed dozens and dozens of cold-blooded killers," DeLong said. "I've interviewed people who killed accidentally, people who lost their tempers, serial killers. Cindy was, stand-out, not in that group. She had a gentle air about her. She just didn't fit in any way to all the people I've interviewed in the last 40 to 50 years."

DeLong believes White. In fact, she said, White is the only incarcerated woman she feels invested in helping win release.

False allegations of child sexual abuse are "extremely rare," DeLong said, and the fact White did not talk about it for years actually gives her credibility. Survivors of childhood sexual abuse never want to talk about what happened to them, Delong explained, and only do so when they feel they're in a safe environment.

"The way she told the story, the things she was saying, the look on her face, the tone of her voice, all of it," DeLong said, "painted a picture of truthfulness."

Not everyone, though, is convinced.

Johnson County prosecutor opposes freedom for White

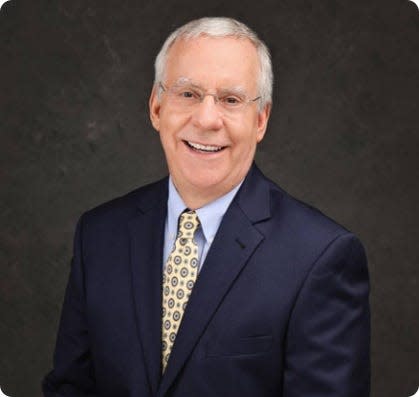

Johnson County Prosecutor Lance Hamner first heard about White in the 1990s after he was first elected prosecutor of Johnson County. At that time, White's attorney asked if he would support a sentence modification.

He refused. Three decades later, nothing has changed Hamner's mind.

In his opinion, nothing excuses the crimes: Not White's tumultuous family life and mental illness. Not her young age at that time. Not what modern-day research shows about childhood trauma. Not Charles Roberson's infidelity. And not White's allegations of abuse by the Robersons.

"As the people’s prosecutor I speak for the people. And I also speak for the dead who cannot speak for themselves," said Hamner, a former police officer and judge who left the bench to run for prosecutor again in 2022. "In Ms. White’s case she murdered not one but six people. Four little children never got to even grow up."

That White did not intend for the fire to turn fatal does not ― and should not ― matter legally and in the grand scheme of justice, Hamner said. And it does not change the fact that she committed arson "with a wanton disregard of the likely consequences of that action."

"Ms. White intentionally set a fire in a house that she knew was occupied. And she knew that everyone was asleep. And she knew that four of the home's occupants were little children," he said. "That is a callous and depraved act by any calculus. And it is inexcusable."

Hamner said the "assumption" that White did not intend to kill the Robersons is a "stretch." He also rejects her account of that night, arguing a fire started with paper would not have spread so rapidly, and the family would've probably made it out alive.

The case of Sarah Jo Pender: 'I deserve to be let home,' Pender said. The man who prosecuted her agrees.

"I think it’s more reasonable to conclude that she would have had plenty of time to wake the family if she didn’t want them to die in the fire she had set," he said.

If White didn't intend to hurt or kill the Robersons, Hamner argued, the then-18-year-old could've simply moved out. "There was nothing legally, morally, or ethically that required her to stay in a home where she claims to have been unhappy."

White has previously said that Charles Roberson threatened her if she tried to leave.

Hamner also does not believe White's sexual abuse allegations against the Robersons. Instead, he described them as "self-serving."

"Anyone can make claims against people who are dead and cannot defend themselves," Hamner said, adding that if the allegations against were true, "it would certainly be a strong motive for murder."

It's plausible White is now remorseful, Hamner acknowledged, and he does feel "sorry for the tragic childhood she had."

"But," he said, "I don’t think anyone believes it excuses what she did."

While a "small vociferous group of" supporters is convinced White has done enough time, Hamner believes most people don't agree.

"What is the appropriate punishment for murder?" he asked. "Most people believe it's either death or life in prison."

Former women's prison superintendent: 'You are not your crime'

Over time, White settled into prison life. She obtained her GED and a college degree. She became a beloved figure among fellow prisoners. Women her age saw her as a friend. Younger women saw her as a mentor. They called her "Mama Cindy," even though she also seemed "childlike."

White avoided trouble and immersed herself in programs and activities, even though no amount of credit time would cut her sentence short. She trained dogs, worked in the kitchen, joined the choir, took care of elderly prisoners, made clothes for nonprofits, crocheted hats and scarves for the needy. She even got her clown certification.

"You name it, she was involved in it," said Dana Blank Row, a former longtime superintendent of the Indiana Women's Prison.

Deborah Mayweathers became friends with White when she served time in prison. She said White studied with her and helped her write essays. Because of White, Mayweathers said, she finished college, making the dean's list twice.

Anastazia Schmid, who also became close friends with White in prison, called her "a beacon of light in that place."

"If Cindy had anything," she said, "she would give you her absolute last if you needed it."

Of all the conversations the two women had, one still stands out to Schmid.

"She said, 'I was never safe until I got here,'" said Schmid, who was released in 2019. "That broke my heart."

Blank Row and several others who got to know White believe she has served more than enough time for her crime. Dianne Cole, one of White's former counselors, wrote in a 1993 progress report that she sees "no benefit to further incarceration."

"How much time is enough time?" the former superintendent asked. She added: "I’ve always told the ladies, 'You are not your crime.'"

That is especially true with female offenders, who studies have shown are far less likely than men to kill again and whose violent crimes are typically tied to an abusive relationship. Blank Row knows this from a lifetime of working in the prison system.

"With women … if they take a life, it’s because they knew the victim and the victim in some way either abused them or took advantage of them," Blank Row said. "Once they have committed that crime against the person that did something to them, they’re over it. They’re not going to hurt anybody else."

For years, Kathleen Cerna, White's younger sister, believed she was innocent. And White's belated confession devastated her because, in some ways, Cerna understood the horror of a fiery death. Her own 3-year-old son had died in a house fire, and knowing that her big sister ― her "hero" ― had caused such pain to other children put her in a state of denial.

But Cerna believes White never meant to kill the family. Far more brutal murderers have spent less time in prison, she said, citing the case of Gertrude Baniszewski, the Indiana woman who was convicted in the notorious torture and murder of 16-year-old Sylvia Likens. Baniszewski was released on parole in 1985.

Cerna, who has several young children, works as a school custodial manager and owns a construction and cleaning business with her husband. The siblings now have a good relationship, and Cerna and her family visit White in prison.

"There's a family out here that love her and need her ... My children, they love her so much," Cerna said. "And they don't understand why she can't come home."

Murder. A conviction. An exoneration: Was evidence of another suspect ignored — or hidden?

Reflecting on her role in fatal fire: 'It won't ever be okay'

White now spends her days in a wheelchair after suffering multiple strokes. She no longer works and calls herself "retired." But she still helps where she can, by crocheting items for mothers to send to their children, folding laundry for friends, helping wash dishes, and making other women birthday cards and singing an off-key rendition of "Happy Birthday."

She’s a mother and a grandmother figure to other inmates, although she herself never bore a child ― a fate White said is probably her ultimate punishment.

She lost her youth and her child-bearing years behind prison walls. She lost friends who, one by one and year after year, were released back into the outside world. Others, she watched die. And despite the permanence of her punishment, White clings to some hope she'll still make it out of prison alive.

"I don’t want to die here. Too many have died here," she said. "And it’s a very lonely death. I’m around 600 women but I’m so alone, and I’m lonely … I cry every day in my heart. Because I’m not a bad person."

One option she has is to file another petition for clemency with the Indiana Parole Board, which then makes a recommendation to the governor. Successful clemency petitions, either in the form of pardons or sentence commutations, are rare and have largely been granted only to those convicted of nonviolent or low-level offenses. In 2022 Gov. Eric Holcomb commuted the sentences of three men convicted of violent crimes, but they were either bed-ridden or required 24-hour care.

Even if she never wins her freedom, White said she hopes people will look at her and see past her crimes. Anita Sewall did — and she was surprised at what she found.

The two women started exchanging letters in 2011 and grew to be friends. In one of her first letters, White told Sewall how she started her own prison garden. She saved seeds from their meals and, when spring came, she used a plastic fork to dig up a patch of dirt outside her unit. She planted tomatoes, cucumbers, green peppers, watermelons, cantaloupe and squash.

"I will be able to give everyone on my dorm some of what I have grown," she wrote.

The daughter of a police officer, Sewall said she wasn't expecting to be drawn to someone serving time for murder. But when she first visited White, she didn't see a killer. She just saw another woman. As different as their lives were ― Sewall had an idyllic childhood riding her bike around her neighborhood in a small Indiana town ― they have many things in common, including their faith.

Their letters eventually led to regular visits at the prison. They saw each other for two hours every Friday morning for several years. If White ever gets released, Sewall and her husband have agreed to let her stay with them in their home in Indianapolis.

White’s crimes were never the focus of their friendship, Sewall said, but they have talked about "that night."

"Out of all her regrets about that night," she said, "those children’s deaths continue to weigh on her."

White still remembers their birthdays and often wonders what their future might have been. They would've been well into middle age by now. They could've grown up to become parents, grandparents, doctors, or the next president of the United States.

But no one will ever know. And White understands she’s the reason.

"It won’t ever be okay," she said. "I don’t care if they let me out tomorrow. It’s still not going to be okay."

Nearly 50 years after the fire, White said she still asks for forgiveness. Every Christmas, she collects candies and arranges them in four little piles, one for each Roberson child.

And every night, before she drifts off to sleep in her prison bunk, White calls out their four names ― Michael, Dale, Gary and Sissy ― and tells them goodnight.

Contact IndyStar reporter Kristine Phillips at (317) 444-3026 or at kphillips@indystar.com.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: At 18, she lit deadly fire. Cindy White, now 66, faces dying in prison