He was part of Amazon's coronavirus hiring spree. Two weeks later he was dead

When Harry Sentoso got called back to work at an Amazon delivery center in Irvine in late March, he was excited.

He had been working in Amazon warehouses on and off for two years, always hoping to get a full-time position but always laid off after seasonal demand died down. Just a few weeks earlier, at the beginning of March, his bosses had told him they didn’t need him anymore. He had spent most of the month cooped up at home in Walnut, looking for other work.

Sentoso saw the warehouse job as a last chance to earn some cash before settling down to retirement. A small business he had started with a friend a few years earlier selling forklift tires hadn’t taken off, and he didn’t want to touch his savings if he didn’t have to. He had applied to dozens of jobs in recent years, but Amazon was the best the 63-year-old could find.

Before dawn on March 29, he left home in his Honda Civic, radio tuned to classic rock, and made the drive down to Orange County to work the early morning shift hauling and sorting packages before they went out to customers’ homes.

Two weeks later, in the early morning hours of April 12 — his 27th wedding anniversary — Harry Sentoso would be dead.

Sentoso's return to work was part of a massive wave of hiring that Amazon has undertaken in response to the coronavirus crisis. In mid-March, the company announced plans to hire 100,000 new workers to deal with a surge in online orders. In April, it began hiring 75,000 more to keep up with demand as it resumed shipping more nonessential items to customers.

With that human wave came the virus. The same week that Sentoso was called back to work, new cases of COVID-19 were reported at six warehouses across Southern California. Until now, no cases at the Irvine facility, known as DLA9, have been made public, and Sentoso's death had gone unreported. Across the country, Amazon workers have documented more than 1,000 cases among warehouse workers as of May 20, and seven deaths. Sentoso is the eighth.

Thousands of businesses have had to close and more than 38 million Americans have lost their jobs since the lockdowns began. But Amazon is hiring. The company has put new measures in place to make its warehouses safer for employees, but the number of cases at its facilities keeps rising. As consumers continue to minimize their own risk by shopping from their couches, workers have to decide: Is working for Amazon a lifeline, or a life-threatening risk?

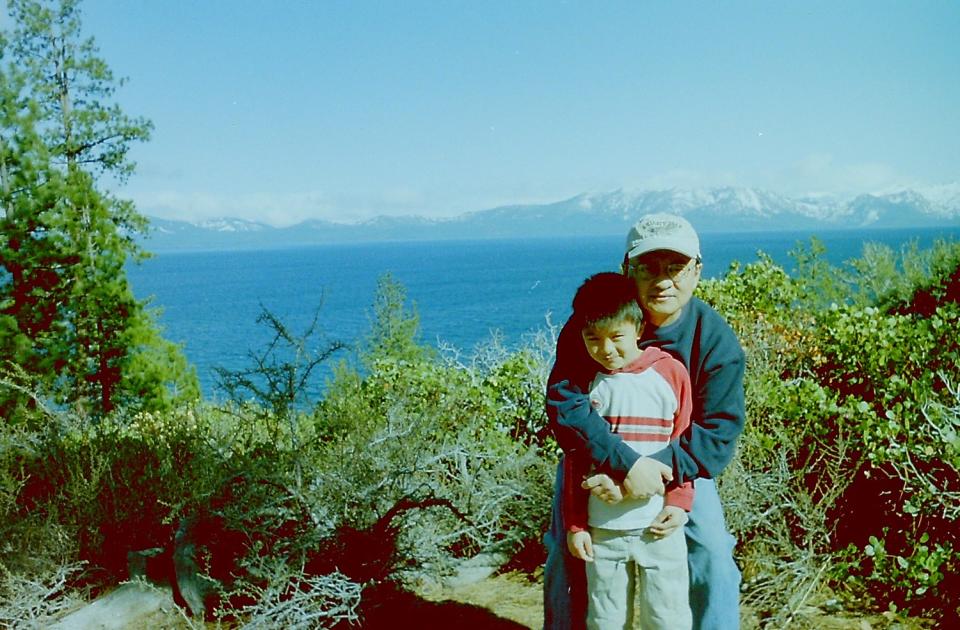

Harry Sentoso moved to Southern California in the 1970s, fleeing anti-leftist violence and persecution in his native Indonesia that targeted his family for their Chinese ancestry. His legal name was Sukoyo, but he chose to go by the short version of his middle name, Hariyadi, in his new home.

After a few hard years scraping by in downtown L.A., he worked in sales for a doll company, then started his own small business, an import-export operation moving construction materials between California and Indonesia. Along the way, he earned a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering and an MBA from Cal Poly Pomona, met his wife, Endang, and started a family. In his 40s, he landed a steady job as the warehouse supervisor at an oxygen sensor manufacturer, and worked there for over a decade.

By the end of his career, he had socked away a healthy retirement fund, bought a house in Walnut, raised two sons, and taken up day trading as a hobby and a passion. He was devoted to his family, gracious and kind — former co-workers recall his upbeat attitude and insistence on paying for lunch. He loved good food, dad jokes, and, according to his 20-year-old son Evan, Mini Coopers.

In short, Harry Sentoso had lived the kind of life that can flourish for immigrants and refugees, if everything goes right, in Southern California’s sun-baked suburban soil.

But things began to go wrong after Sentoso returned to work in late March. He worked from Sunday to Thursday, then started to feel a little under the weather on Friday, the first of his two days off. (The median incubation time for coronavirus infections is five days.)

On Sunday, April 5, he went back to work, anxious not to miss a shift so soon after getting his job back and convinced he could shake what he thought was a cold, or maybe just bad indigestion. He liked to tell his sons, and the co-workers he befriended who were his sons' age, that working at Amazon was great for his health — long days on the warehouse floor meant he always got in all his steps.

But on the same day, his wife started feeling sick. Sentoso worked four more days, hauling and sorting boxes for delivery to their final destination, but then started to feel worse: shortness of breath, cough, fever. His wife, a pharmacy technician who made sure he brought and wore a mask to work every day, got tested at her workplace on Wednesday. Her results came back positive, and the family doctor said it was safe to assume her husband was too. They both began to quarantine.

Three days later, close to midnight on April 11, Sentoso was having trouble getting any oxygen at all. His wife and older son Dylan, 22, tried to get him to the car to take him to the hospital, but Harry fell unconscious on his driveway. She called an ambulance, and called her other son.

Evan, a student at UCLA, borrowed a classmate’s car and raced across the empty freeways from Westwood to Walnut alone, hoping he might be able to see his dad before things got worse. But he was too late. The EMTs had managed to briefly raise a pulse on the way to the hospital, but it had disappeared again by the time they arrived.

His father was gone. Hospital staff allowed Evan 10 minutes in the ICU, standing a few feet away from his father's body, to cry and say his last goodbyes.

In a statement, Lisa Levandowski, a spokesperson for Amazon, said: "We are mourning the loss of an associate at our site in Irvine, California. His family and loved ones are in our thoughts, and we are supporting his fellow colleagues in the days ahead."

Evan moved back in with his older brother and his mother after his father’s death. The family was forced to mourn behind masks in their own home, the two sons watching and waiting as their mother got sicker, their father’s ashes still in their urn.

Evan started getting calls from Amazon HR. There was someone from the Leave of Absence team, asking where Harry Sentoso was. After Evan told them that his father had died from complications of the coronavirus, he got a call from the company’s Employee Resource Center, asking to confirm that his father had died. Then someone from Amazon’s Global Security Operations called to confirm that his father had died. An Amazon employee called from Chile for the same reason. Finally, the local HR team finished up the phone chain.

That same week, Amazon announced that it was going to expand shipments of nonessential items, and was hiring a second wave of 75,000 new workers to process the flood of orders (up until that point, they had been prioritizing orders that they deemed essential). Amazon also fired two tech workers who had publicly criticized safety and working conditions at the company's warehouses.

His outrage growing, Evan called the local HR rep back to ask some questions.

“Why are you hiring people if you’re shipping out nonessential goods?" Evan asked. “Someone’s life is not worth less than some person’s board game.”

He wants to know why Amazon isn't being more transparent with its workers and the public. The company's official policy states that it informs all employees who have come in contact with an infected worker, but Amazon refuses to release official numbers of cases or deaths among its workforce.

Reached for comment, Amazon said that it never received confirmation that Sentoso's death was linked to COVID-19, so it did not send out a mass notification, and only informed his co-workers verbally of his passing.

When Evan first spoke with multiple Amazon representatives, he and his family had not yet received the postmortem test results from the hospital confirming that his father had been infected with the virus. But he told Amazon how his father died, that his mother had tested positive, and that a doctor had told the family to assume his father had the virus.

Once the results, which have been reviewed by The Times, came in, Evan says he tried calling Amazon twice to inform the company, but was never called back. Soon after, Evan's family retained a lawyer to file a worker's compensation claim with the state, which listed the coronavirus as his father's cause of death.

He wants to know why the company was planning to stop allowing workers to take unlimited unpaid time off if they're afraid to go in to work, and why Amazon is ending its $2 pay bump for workers if the coronavirus pandemic in the U.S. shows few signs of slowing down.

On the call, Evan said, the company ran through the litany of safety procedures that it put in place since the virus began to spread. The week before Sentoso died, the company began requiring employees to wear masks on site, and started checking the temperature of workers before they could enter. It began requiring employees to stay six feet apart in late March, and staggered shifts and canceled in-person meetings to make that easier. The company has increased the frequency of cleaning and disinfecting in warehouses as well, and began spraying down whole facilities with disinfectant fogs in mid-April.

But Evan, and a contingent of Amazon workers across the country, don't think that those measures are enough. Hundreds of workers at Amazon's facilities in Hawthorne and Eastvale, in Riverside County, have signed and submitted petitions asking the company to close the facilities for two weeks after infections for thorough cleaning and send workers home with quarantine pay. Following worker complaints compiled by the Warehouse Workers Resource Center, Cal/OSHA has also launched investigations into both facilities.

The call for a shutdown has been especially loud at warehouses in Pennsylvania and New York that have become coronavirus hot spots, with more than 60 reported cases at each before the company stopped updating the tally even to local employees.

Other countries facing coronavirus outbreaks show how things could be different here. In India, factories where workers test positive are forced to shut down. In China, people who have come into contact with anyone who tests positive are required to undergo strictly enforced seven- or 14-day quarantines.

Even after the number of new cases in the country dwindled to single digits in April, Chinese factory owners worried that a single infected worker could force the entire workforce into isolation. Foxconn, the million-employee company that builds the iPhone and many other electronic devices, created 20-person teams of workers and required them to work, travel, eat and sleep together in company dormitories to ensure that any infected workers could be quickly traced and quarantined.

In France, a court ruled that Amazon had to restrict its activities to only shipping essential items or face serious fines. The company shut down all six of its large fulfillment centers in the country in response, but kept paying all workers their full salaries. Earlier this week, Amazon reached a deal with the court and the labor unions that brought the case in the first place: Starting June 2, the company will spread out shifts and run its warehouses at only half capacity, to increase social distancing, while continuing to pay the full salaries of the remaining workers left at home.

In California, brick-and-mortar retailers of nonessential goods were required to shut their doors from March 19 until early May to prevent the spread of the coronavirus, but delivery warehouses remained open.

Amazon has been working to create its own infrastructure in order to test all workers regularly, but no state in the U.S. has the available capacity to test at the scale necessary to detect carriers of the virus across the workforce.

Evan and his family are still reeling from his father's death, but he says he draws on his father's memory for strength. "He wouldn't have wanted me to give up, say this isn't fair and cuss my life out," Evan said. And he hopes that in sharing it, he can save other families from his own grief.

"The last thing I want is for another family of another worker to go through what we have," he added. "If there's anything I can do to prevent another illness, another death, that's my goal."