Paso woman picked up by sex offender has been hospitalized more than 50 times in 4 years

Editor’s Note: This is the second in a two-part series about Ashlynn Miles, a mentally ill Paso Robles woman who was picked up by a sex offender after she was released early from a county psychiatric facility. This article discusses topics related to sexual assault, self-harm and suicide. Please read with care.

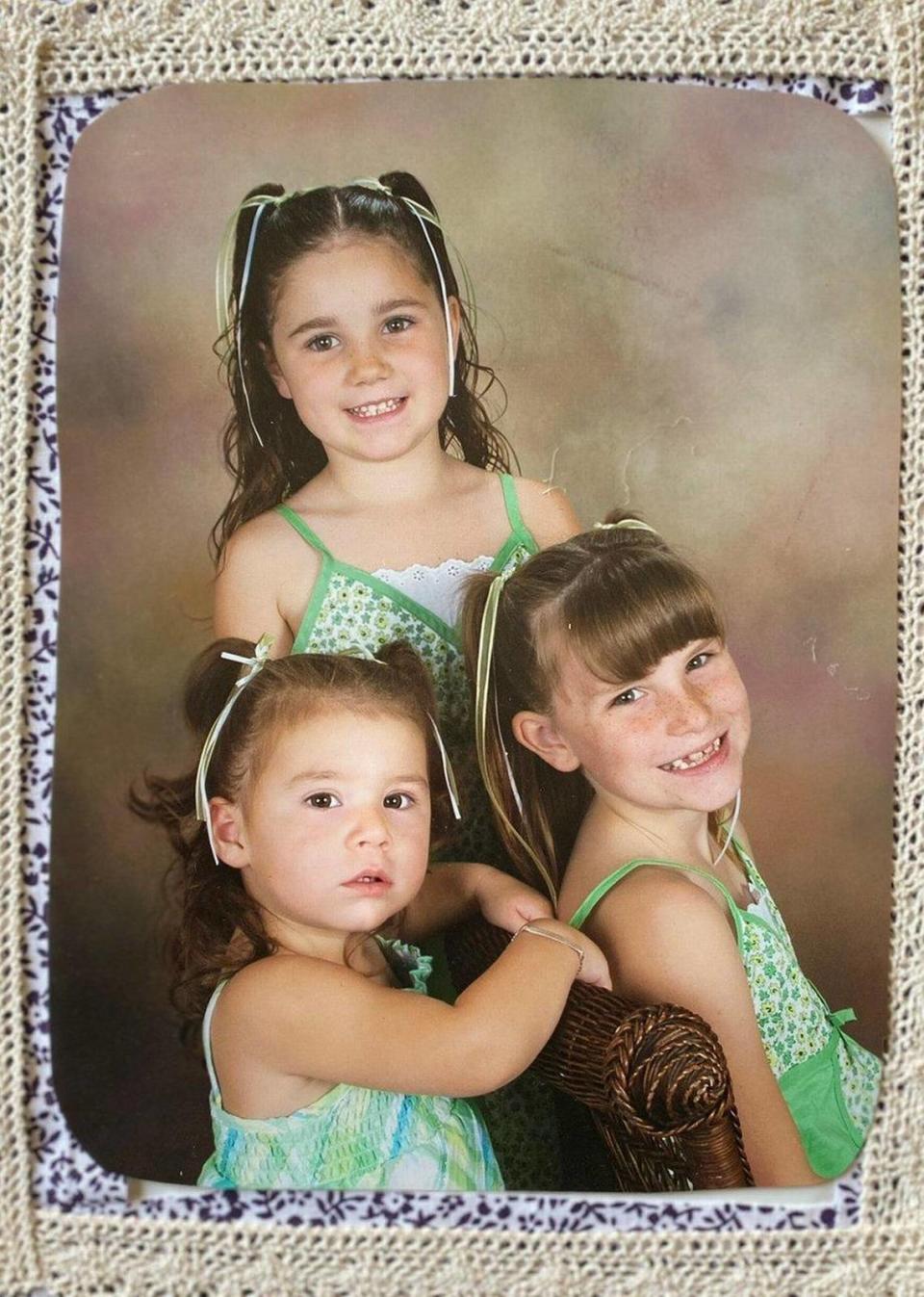

Ashlynn Miles of Paso Robles was a young child when she was unofficially diagnosed with schizophrenia, but after a head injury followed by the death of her ex-boyfriend when she was a teenager, her mental illness became more severe and her delusions became all-consuming.

Kimberlee Booth, Miles’ mother, had every reason to be concerned: Her daughter has a history of mental illness on both sides of her family.

In just four years, Miles, now 22, went from being an outgoing hometown girl who attended Cuesta College, rode dirt bikes and loved children, animals and parties to homeless with severe schizophrenia and a secondary substance use disorder.

“She used to be afraid of her illness,” Booth said. “Now that’s all she knows.”

Miles has been the victim of numerous instances of physical and sexual violence as her mental illness made her highly vulnerable to dangerous situations.

Earlier this month, Miles hitched a ride from Paso Robles with a trucker who ended up being a registered sex offender. She thought she was going to Las Vegas but was found by police in the back of the trucker’s cab in Arizona thanks to an AirTag her mom sewed into her backpack.

Delusional and confused, she was immediately hospitalized — hundreds of miles from home.

The frightening episode was just the latest in a series of traumas Miles has experienced in recent years.

By her count, Booth said, Miles has attempted suicide eight times, been raped 12 times, was stabbed once and was beaten on countless occasions.

Booth thinks there are even more violent incidents in her daughter’s past that she doesn’t know about.

As her schizophrenia becomes more severe and remains untreated, Miles has threatened the safety of her family and others in the community with physical violence.

In April 2022, Miles was held in a Nevada psychiatric hospital for five days after attempting to kidnap a child in Las Vegas, according to her medical record.

Miles’ schizophrenia has made her act violently toward children and the rescue animals on her mother’s property to the point where Child Protective Services said the she cannot live there while Booth has kids in her care.

Miles has now been homeless since December 2020. The family has spent the last four years in crisis.

“She’s haunted 24 hours a day,” Booth said. “(Her illness) completely destroyed us.”

Paso Robles woman hospitalized more than 50 times in 4 years

Booth has kept every document related to Miles’ medical history.

Her kitchen table is stacked with boxes and boxes of medical paperwork, most of it from the past four years of her daughter’s life.

In January 2020, Miles agreed to give her mother power of attorney over her medical and financial records, which allows Booth to access these materials when Miles is deemed unable to care for herself — such as when she is placed on a mental health hold.

The documents represent hundreds of interactions with behavioral health hospitals and agencies in San Luis Obispo County and other California counties, as well as medical and psychiatric hospitals in Nevada, where Miles first went missing, and now similar facilities in Arizona, where Miles is currently hospitalized.

The Tribune reviewed nearly 2,000 pages of medical records that showed how Miles’ schizophrenia worsened under the county’s patchwork care.

The majority of the documents represent touchpoints between Miles and San Luis Obispo County Behavioral Health Services, where she received inpatient and outpatient psychiatric services because she is a Medi-Cal recipient.

The services ranged from low-tier — such as visits to the county-run Crisis Stabilization Unit in San Luis Obispo (a step down from a locked facility), outpatient visits and calls with social workers — to higher-tier, such as inpatient hospital stays at locked facilities like the county Psychiatric Health Facility (PHF, pronounced “puff”) or psychiatric hospitals outside the county when Miles is deemed a danger to herself and others or gravely disabled, according to medical records shared with The Tribune.

Including medical screenings related to mental health holds and emergency room visits for ailments like frostbite caused by her homelessness, Miles has been hospitalized more than 50 times over roughly four years.

The records show that Miles, who has a history of drug use, was oftentimes not under the influence of drugs at the time of her hospital intake. That means her mental illness was the key factor driving the psychosis that led to her mental health hold and subsequent hospitalization.

The hospitalizations figure is likely an undercount, because the number is based only on the medical records Booth could find and access.

Booth thinks there are likely many more interactions with hospitals that she simply doesn’t know about and her daughter may not remember.

“Could you imagine the millions of dollars these states have paid for my kid? Let’s just put a number on it — people don’t want to spend money on mental health care,” Booth said. “Well, then help them.”

Woman experienced schizophrenic delusions as a child

Miles is Booth’s second-born child in a family of five children and two step-children. Booth gave birth to Miles when she was 19 years old.

As a child, the curly-haired girl was always very bright and spoke in complete sentences, but — unlike her older sister Kaila Wright— she never wanted to be held and was content to stare up at the sky, Booth said.

Miles’ teachers at Pleasant Valley Elementary School in San Miguel described her as “such a wonderful blessing,” Booth said. “But they would tell me that she didn’t have any friends.”

Meanwhile, however, she said, “Ashlynn would always tell me ‘oh my gosh, Mom, I have so many friends at school.’”

Teachers told her Miles would sit on the bench and whisper to herself.

“I should have known,” Booth said. “I should have known.”

Miles was diagnosed with childhood schizophrenia at 5 years old, Booth said. The diagnosis was different from schizophrenia seen in adults, because some doctors are hesitant to diagnose minors with severe mental illness due to the potential of lifelong stigma.

Booth didn’t tell her daughter or anyone in her family about Miles’ mental illness in the hopes that she would live her life free of feeling judged or hindered by her disability.

In her childhood, “some things happened, but I just thought they were quirky, not too bad things, ” Booth said.

Booth said she started her home-based Vintage Tortoise Rescue for her daughter, who was deeply compassionate toward animals.

At Pleasant Valley Elementary School, which was a K-8 campus, Miles enrolled in a teacher’s pigeon program that taught students how to train carrier pigeons to fly to Morro Bay and back. Miles was deemed the “pigeon master” because she was so good at caring for and training the birds.

“She’s more like me than anybody,” Booth said. “I taught them to love animals and nature and family, and she’s the one that got it. I didn’t even really have to teach her. She was just like born that way.”

Before her illness took hold, Booth said, her daughter had a big heart and always rooted for the underdog. She recalled a time where Miles gave away her new jacket to a schoolmate who was homeless and lived in his car with his mom behind the school.

‘She’s sick and there’s no help,’ mother said

Miles’ schizophrenia had already begun to crop up more in her later teen years, but after the death of her ex-boyfriend, Sean Schultz, in a car crash in San Miguel, her mother said it took on a new severity. Soon, she started experiencing delusions of her deceased ex-boyfriend tormenting her at night.

“She’d say, ‘Mom, he’s tickling me, but it hurts,’ and ‘Mom, he’s screaming at me at night,’” Booth said. “She was so afraid of what she thought was him.”

Despite these challenges, Miles graduated from Liberty High School in Paso Robles in 2018.

Her first psychotic break came on the heels of that celebratory event.

At her family graduation party, Miles became convinced one her younger cousins was being sexually abused — a delusion produced by her schizophrenia, Booth said.

Miles spent the entire night of her graduation party calling police and agencies. San Luis Obispo County Child Protective Services came to investigate her extended family, including an invasive exam of her young cousin. Their investigation showed the abuse allegations were unsupported, Booth said.

“The police report said that if she called one more time, they were going to come and arrest her, because she was calling every agency,” Booth said. “They said that it had to have been somebody mentally ill.”

The incident fractured the extended family. It became clear Miles needed the support of mental health professionals, Booth said.

“She graduated from here, went to college here, was in tons of programs in our community and then — boom — she’s sick and there’s no help,” Booth said.

Ashlynn Miles remembers the person she was before her illness

On Sept. 15, while admitted to Southwest Behavioral Hospital in Phoenix, Miles talked to The Tribune to share thoughts about her life in her own words.

She landed at the psychiatric hospital after being taken to the state by a sex offender.

As she talked about the things she loved in life, Miles spoke in the past tense.

“Dude, I used to be so outgoing ... well, in my own world outgoing. I used to draw. I used to run. Take hikes. Sometimes I would go to parties and get really drunk,” Miles said with a laugh. “I had a really good bond with all my friends.”

When asked about why she used the past tense, she said it’s because she’s been “off her hinges” from depression and mental illness.

Miles said she’s tried to pull her life together, but it’s been a struggle.

“Sometimes I’ll be looking for jobs, but I won’t find them because my hair is never (done) or like my outfit is never on or looking good or something,” she said. “It’s hard to find a job.”

Miles said multiple times that she’s struggled with things like knowing how to pay bills and organize her life as an adult.

Miles’ older sister Kaila Wright, 24, listened to the call between Miles, her mother and the Tribune.

Miles’ struggles with paying bills and finding a job are symbolic of the barriers her disability has created, Wright said, noting “she can’t sit down and learn the complexity of living a regular life.”

Miles said family support would help her feel less depressed and more stable, Wright said.

“I think (it helps) knowing that there was a holiday and that my mom was going to pick me up, or knowing that there’s a family occasion,” Miles said. “I love my family. I love my little brother, little sister, all of them.”

Booth said she knows that family support makes a huge difference for her daughter, because they’ve successfully managed to keep her out of the hospital for a full year before with regular therapy, medication and the help of loved ones.

At this point she’s afraid her daughter’s mental state has devolved to the point where those types of interventions will fail.

How COVID-19 upended family’s stability

After experiencing her first psychotic break in the summer of 2018, Miles was placed on at least two 5150 mental health holds and transferred to the county Psychiatric Health Facility for care.

“Of course, in 2018 when she had her first psychotic break, we got right on that, started medication, started therapy,” Booth said. “So then in 2019, that’s where you’re seeing it kind of work.”

Based on available medical records, Miles was not hospitalized at any point that year. But that doesn’t mean it was smooth sailing for Miles or her family.

Aggressive outbursts caused by her schizophrenia meant the family was safer with Miles staying in an RV camper parked behind the house instead of living with her in the family home.

Five days a week, social workers from Family Care Network, a San Luis Obispo nonprofit community-based organization, visited Miles in the camper to check on her, go for walks and teach her grounding exercises. She also saw a psychiatrist weekly for medication management.

During that period, Booth said Miles attended Cuesta College and even started her own online business selling false eyelashes — she always loved makeup.

After a while, however, she started telling her family that she felt the medication wasn’t working, and that her hallucinations were getting stronger.

Around that time, Miles also started displaying violence toward her family, particularly her younger sister.

Once, they found broken glass in the beds. Another time, Miles put bleach in a baby bottle.

After a while, the family had to put keypad locks on the doors to keep her away from the main house.

The police often had to be called to the house that year, though Booth never pressed charges and tried to keep Miles out of the hospital and jail.

“We handled it as a family, if that makes any sense,” Booth said. “There was shit going down, but we kept it to ourselves pretty much.”

In March 2020, the COVID-19 lockdown hit, and the in-person support Miles relied upon stopped almost overnight.

“They went away completely,” Booth said.

Miles’ therapy appointments switched to telehealth, which isn’t a particularly effective method for connecting with someone with severe schizophrenia, she said. Booth said she’s afraid of the phone, Zoom, etc.

Many times, the psychiatrists who were supposed to administer her injections just didn’t show up.

Soon, Miles started to “decompensate” — a psychological term referring to a breakdown in a person’s defense mechanisms resulting in progressive loss of normal functioning or worsening of psychiatric symptoms, according to the American Psychological Association.

“It wasn’t even her fault. It was 150% their fault,” Booth said. “I mean, they just dropped us.”

Near the end of 2020, Miles started telling her family the medication stopped working and that her voices were getting louder.

Around this time “(Miles) said she wanted a normal life, that sometimes it feels like she has to hurt herself, and she just wished the meds would make her schizophrenia go away,” wrote Miles’ maternal aunt Jennifer, who asked to be identified by her first name, in a September 2021 letter to the county urging conservatorship for her niece.

As a result, Miles lost trust in the system, and she stopped taking her medication.

She also refused to sleep in the camper, telling her family she was afraid rapists and murderers were getting into her space at night. Booth tried to let her stay in the downstairs bedroom, but her schizophrenia caused her to continue to display violence toward her family.

In December 2020, Booth had no choice but to leave her daughter at the 40 Prado Shelter in San Luis Obispo, managed by the Communication Action Partnership of San Luis Obispo (CAPSLO).

“I’ve literally had to choose children,” Booth said. “I’ve been put to that point.”

How Ashlynn fell deeper into schizophrenia

Wright is 18 months older than her sister Ashlynn. While growing up, the two were always together and shared everything — from their friend group to their bedroom.

“She was my best friend, but she was my sister, too,” Wright said. “I used to be able to count on her for anything, and it was like that for her too.”

The sisters shared a bedroom and decorated each half. Wright’s side was often beach-themed or had a lot of pink, while Miles’ side was a little different.

“During the start of her illness, she started decorating the room with pictures that she would draw,” Wright said, estimating her sister was about 16 at the time. The drawings were abstract images of eyeballs and figures that represented the paranoia Miles was experiencing.

Around the same time, Wright said she witnessed her sister’s violent assault at the hands of a teenager from another school.

“I thought my sister was gonna die,” Wright said. “(The girl) smashed my sister’s head into the concrete like 16 or 18 times.”

Wright’s observations about her sister’s assault and rising paranoia coincided with Miles’ first interaction with San Luis Obispo County Behavioral Health Services.

In April 2016, Booth called the county to share her concerns that Miles had post-traumatic stress disorder after the assault, according to medical records shared with the Tribune.

“Client was assaulted by her significant other last year and sustained injuries,” the medical record said, though Wright did not describe the student who assaulted Miles that way. “Her sister witnessed the assault and is receiving therapy at the North County clinic. Client is home-schooled. Mom reports client experiences social anxiety. Client is sleeping excessively. Client has history of depression and has received therapy in the past.”

Medical records show Miles failed to show up for her intake assessment scheduled for a week after Booth’s call.

“I think the head trauma really played a big part in her schizophrenia being developed to where it is,” Wright said.

What life is like with schizophrenia

By the time she was 18 years old, Miles’ schizophrenic delusions and substance use disorder became more severe, and she required more intensive psychiatric care.

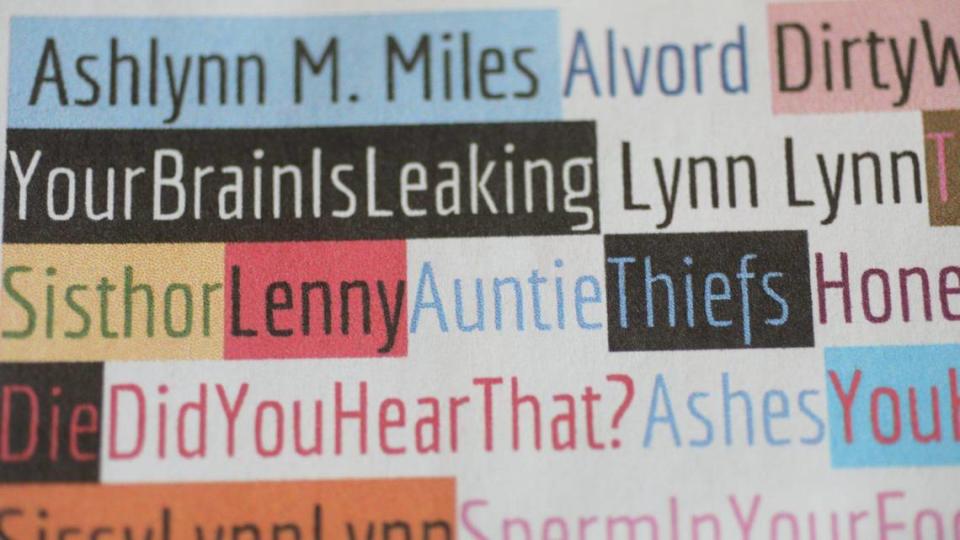

Her medical record chronicles many instances where Miles is uncertain what is real and what is a delusion created by her mental illness.

According to her medical record, Miles spent four days at the PHF in January 2020 after being placed on a 72-hour hold for suicidal ideation.

“She has been keeping a list of things she experienced since yesterday: Hears people talking to her through the loudspeaker, the bathroom glass, through traffic (hears traffic sounds and makes voices out of it), heard one of the patients whisper to her but she’s not sure if she’s talking out loud or thinking things, always hears babies being beat, constantly hears people having sex ...” according to a note in her medical record dated Jan. 19, 2020.

She was discharged from the facility the next day.

In April 2020, when Miles was 20, she was seen for an outpatient visit with San Luis Obispo County Behavioral Health Services.

“Ashlynn ... has been having a difficult time differentiating if her dreams are ‘dreams or reality’ and that she is maybe sleepwalking. Ashlynn reports that her dreams consist of her ‘walking into traffic or saying hi to the mailman,’” according to her medical record shared with The Tribune.

In May 2020, Miles told clinicians she thought she saw her mother drowning a baby, only to realize the baby was fine. “The patient states she is having some delusions,” according to the record.

Booth said watching Miles try to navigate her mental illness was devastating to watch.

“She was so confused,” Booth said. “(The delusions) are real to them.”

One of Miles’ most painful delusions for the family is the belief that Wright’s 3-year-old daughter is actually hers.

“She strongly believes that my daughter is hers,” Wright said. “I want to be there for my sister, but also, she will harm my child.”

Wright said she’s forced to keep her sister far away from her daughter to protect the girl’s safety.

“And that’s extremely hard, because if she didn’t have this mental illness, she would be the best aunt in the entire world,” she said.

Medical records shared with The Tribune show between August 2018 and August 2022, Miles was hospitalized at the PHF 11 times.

From August 2018 to October 2021, Miles was placed on 18 mental health holds in San Luis Obispo County alone, according to a public guardian meeting recorded by Booth and shared with the Tribune.

She’s had numerous hospitalizations in emergency rooms and psychiatric facilities outside the county.

“Client has been hospitalized 7x out of county over the last few months,” according to a note in her medical record dated July 8, 2021, when Miles was homeless in the Orange County area.

In between psychiatric hospital stays, Miles visited at least six drug and alcohol rehabilitation centers by Booth’s count. She said Miles is usually kicked out of these establishments or simply leaves.

While homeless in Nevada for seven months of this year, Miles was hospitalized 10 times — seven times in psychiatric facilities — based on medical records reviewed by the Tribune and a list compiled by Booth.

“It’s almost every single time she has been in a hospital that she needs to be in a lockdown facility,” Booth said.

Family tries to keep their homeless daughter safe

In early January, Miles was interviewed by The Tribune for a story about a homeless encampment sweep along the Bob Jones Trail in San Luis Obispo.

As she cleared out her belongings, she told the Tribune that being homeless was akin to committing suicide.

Miles and other people who were living in the encampment were evicted due to a safety improvement project.

Booth said she wrote to numerous government officials after the eviction and told them “you literally killed my f--king kid. You made it to where she can’t even live here.”

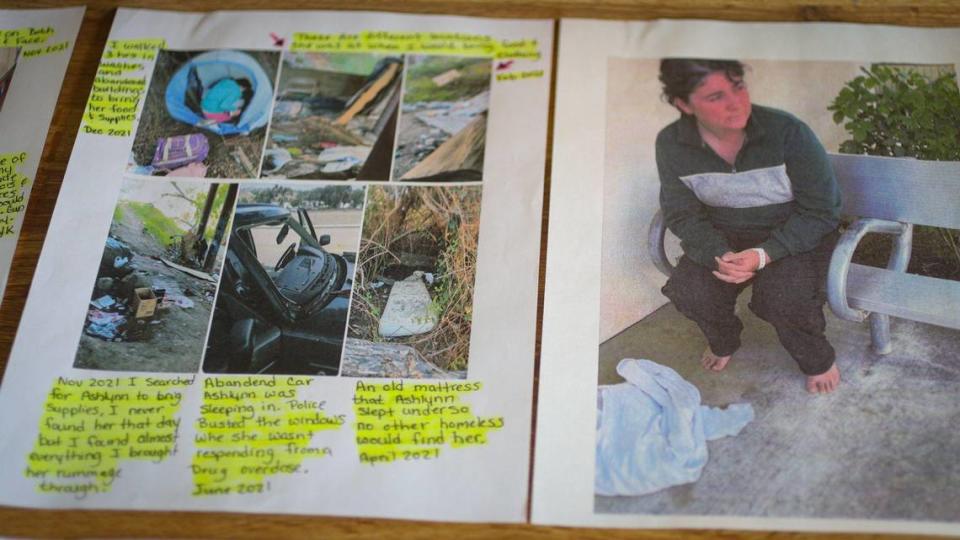

Candyce Carrasco, 18, Miles and Wright’s younger sister and Booth’s third daughter, has tried to help Miles through homelessness multiple times. Of the family members, she, her mother and Miles’ step-sister, Ivy Carrasco, 25, have devoted the most energy to trying to keep Miles safe.

Candyce Carrasco and her mother have traipsed through homeless camps searching for Miles, dropped her off at encampments since she isn’t safe to bring home and picked Miles up when she’s in trouble.

“We’ve been in a lot of dangerous situations. I feel like I’m kind of traumatized,” Carrasco said.

Carrasco said the family dynamic has changed dramatically in the past four years as Miles has grown sicker and her mother has become more absorbed in her care.

“The whole house feels it,” Carrasco said. “Every single day is a crisis for her.”

The experience has affected Carrasco so significantly that the Cuesta College student hopes to study psychology so she can one day help people with severe mental illness like her sister.

Her older step-sister Ivy Carrasco is also pursuing a career in mental health services based on her experience with Ashlynn. Kaila Wright is also working in the medical field.

Despite her interest in her studies, though, “it’s hard to focus,” Candyce Carrasco said.

She has struggled in her high school and college classes because of the stress surrounding her sister’s mental illness.

“I feel like my mind is kind of always on Ashlynn — scared for her,” Carrasco said.

Homelessness and mental illness make woman doubly vulnerable

The family’s fears surrounding Miles’ safety are warranted.

Miles has been banned from the homeless shelters in the North County and San Luis Obispo because she is too dangerous, Booth said.

Child Protective Services said Miles can’t come to the family home because she is too violent, leaving her with one option — sleeping outdoors.

In an interview with the Tribune on Sept. 15, Miles said she tried to get protection from the homeless shelters in the community but wasn’t allowed inside, even to charge her phone.

“I didn’t know why I got kicked out, and then I kept trying to fill the paper out to come back in,” Miles said.

She was referencing her eviction from the 40 Prado Shelter in San Luis Obispo, from which she was banned in 2021 for allegedly violent actions.

“They just kept kicking me out for no reason saying that my paperwork ... or I did another thing wrong, I did another thing wrong. When I really only did one thing that was wrong,” Miles said. It was unclear what that incident was.

Miles said she’s afraid of sleeping outdoors.

Booth said Miles uses methamphetamine as a survival drug because sometimes she needs to stay awake for days to stay alert without shelter. She also uses drugs to self-medicate, Booth said.

“There’s been a lot of things (that happened), but it’s been a while since I’ve been thinking about them,” Miles said.

‘I didn’t even think she was alive to be honest with you’

Although Miles struggled to recall the numerous incidents that left her vulnerable over the past four years, her mother has been keeping track.

In September 2021, Miles cut off her hair because she said it made her a frequent target of sexual assault while homeless.

A photo taken by Booth in 2021 shows an old mattress Miles sleeps under to hide from possible abusers.

Nevertheless, just a few days after cutting her hair, Miles was raped near Home Depot in San Luis Obispo and was discovered by a community member terrified, bleeding and without pants, according to her medical record.

Her history as a victim of violence is why, when Miles called Booth late one January night and told her she was moving to Las Vegas with a new friend, Booth was terrified for her daughter.

“She called and woke me up, stating she was moving to Vegas because it was cheaper to live and could I give her money for an apartment,” Booth wrote in a timeline of events she shared with the Tribune. “She said, ‘Mom, I can’t even sleep in a dirty cold riverbed here.’ I couldn’t argue her point but was desperately grasping at straws in fear of her safety.”

The next day, Booth received “terrifying” text messages and photos from her daughter, who said she had been kidnapped and was taken to the middle of nowhere to be murdered at a satanic abandoned house.

“The pictures she was sending were of exactly that, in the middle of nowhere at an abandoned graffitied (sic) structure. She was frantic but still could not tell me who she was with or where she was,” according to Booth’s timeline.

Miles had been taken to the Mojave Desert, where she was physically and sexually assaulted, Booth said. Her injuries were so substantial that first responders on the scene thought she was a young boy who had gotten in a car accident, she said.

In the aftermath of that episode, she spent about three weeks at a medical hospital in Henderson, Nevada, before being transferred to a psychiatric hospital. After being discharged from that hospital, she was a missing person.

“I didn’t even think she was alive to be honest with you,” Booth said.

It wasn’t until August when police identified her after a second violent attack in Nevada that Booth was able to locate her missing daughter.

“Nobody’s looked for Ashlynn’s assailant. Not one f--king person has looked for her assailant,” Booth said. “Nobody’s protecting her. They’re sticking her right back out there knowing what happens every single time.”

What happens now?

Miles’ family feels the best way to keep her safe is to secure intensive psychiatric treatment at a locked facility.

“I’m not saying that I want my kid indefinitely locked up, but I’m saying that I think my kid needs to be indefinitely locked up for her own safety,” Booth said.

Psychiatrists who assessed Miles recently agreed with her.

After Miles was admitted to the San Luis Obispo County PHF in August, a psychiatrist who assessed her recommended a hearing with the county Public Guardian Office to review her case.

When appointed, the public guardian essentially acts as the individual’s parent, making decisions for them about finances and involuntary psychiatric hospitalization for those who need it. For a person deemed gravely disabled by mental illness, a Lanterman-Petris-Short (LPS) conservator may be appointed.

The PHF’s petition for Miles to be appointed a public guardian was denied on a technicality. The office wanted to see her medical record from her time as a missing person in Nevada.

After being discharged from the PHF, Miles hitchhiked to Arizona in a delusional state. She was found hidden in the sleeping compartment of the truck driver’s vehicle and was placed on a mental health hold and hospitalized at a psychiatric facility in Phoenix.

An Arizona psychiatrist who assessed Miles during her stay at Southwest Behavioral Health said she requires long-term psychiatric treatment at a locked facility, Booth said. If she was an Arizona resident, they would have placed her at the locked Arizona State Hospital, managed by the Arizona Department of Healthcare Services, Booth said. Since she is a resident of California, she needs to return to her home state to be hospitalized.

Wright said she thinks having access to food, medication and a safe place to sleep helped her sister stabilize a bit in Arizona, but the family knows this placement is only temporary.

“I think to have some rest, for not only me, but my whole entire family, would be just (having) one facility that would be able to help her,” Wright said.

She thinks an extended stay at a psychiatric hospital to help Miles stabilize, followed by placement at a residential treatment center for people with psychiatric illness, could help her sister live a safer life.

“I love my sister, but hearing that my sister is getting raped on the streets and that I can’t physically help her, it will literally put me down for a week. I can’t hear that,” Wright said.

Behavioral Health declines to help Ashlynn

Ashlynn has been hospitalized at Southwest Behavioral in Phoenix since being found with the sex offender over Labor Day weekend.

Miles’ care coordinator reportedly has been trying to get the SLO County Psychiatric Health Facility to agree to transport Ashlynn from the Arizona border back to San Luis Obispo.

But as of 2 p.m. Wednesday, an email was sent from the PHF to Southwest Behavioral stating the agency is unwilling to transport Miles back to the county and will not be readmitting her to the facility because her mental health hold in Arizona has lapsed, Booth said. Miles was on the hold for a little more than two weeks.

“They’ve had all of this time,” Booth said, noting the PHF has yet to send any medical records to Arizona hospital.

For Miles to be readmitted to the PHF, she would need to break the law or be placed on a new 5150 by evaluators (for grave disability or attempting to injure herself or others), Booth said the care coordinator told her.

“Basically, she needs to get raped, beaten or taken again for her to go back to the public guardian,” Booth said.

The state with the most records on Ashlynn’s mental health is California, which is why authorities in Nevada and now Arizona told Booth they can’t proceed with conservatorship with such limited documentation of her mental illness.

And since the judge ordered outpatient therapy for Miles, Southwest Behavioral has no choice but to discharge her to the streets of Phoenix on Friday morning.

“(San Luis Obispo County Behavioral Health) is really the only people who can help Ashlynn,” Booth said with despair. “I just have to wait for her to get hurt again.”

How to get help

If you are experiencing a mental health crisis or need help finding mental health resources, call the Central Coast Hotline at 800-783-0607. You may also call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255 or text HELLO to 741-741.