A passion for parks: This Texas family loves the outdoors and knows how to write about it

Few Texas families have done as much for the state's natural legacy as the Bristols of Austin and Fort Worth.

For instance, Valarie Bristol, former Travis County commissioner and avid birder, led the charge to preserve the Balcones Canyonlands and other crucial natural habitats in Central Texas. With her daughter, Jennifer, she is finishing up a book on the women who have led the state's conservation movement.

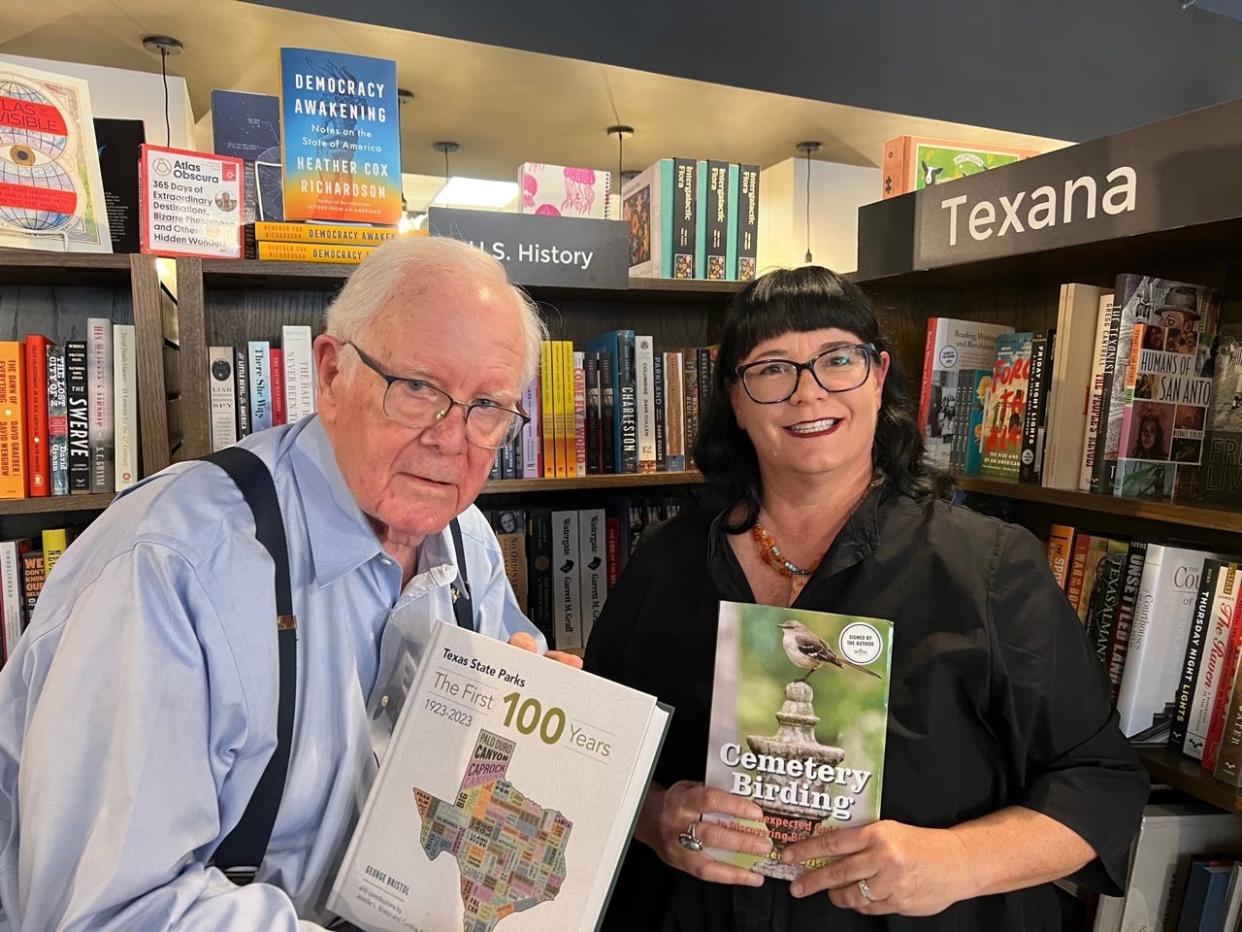

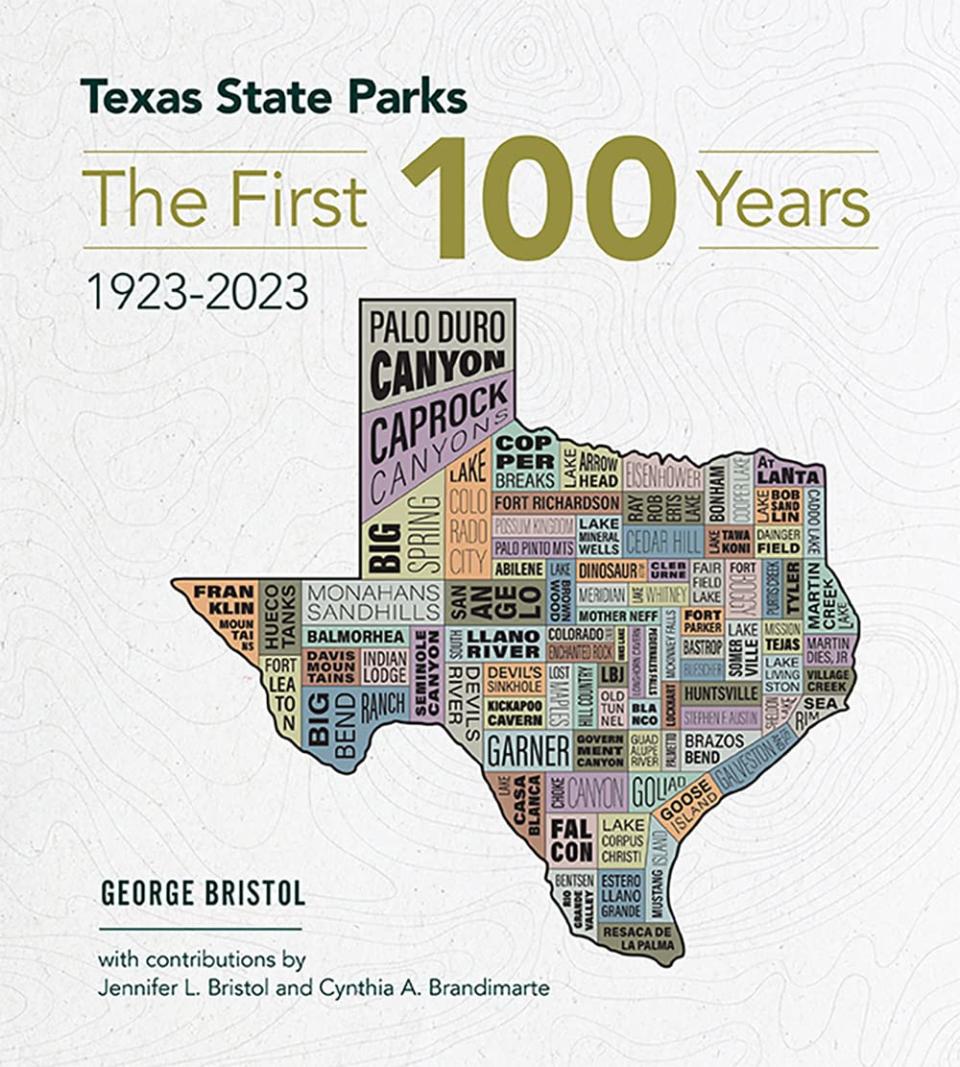

George Bristol, Valarie's former husband, a political insider and onetime National Parks Foundation Board member, is credited with pushing through the 2019 state constitutional amendment that permanently set aside the sales tax on sporting goods to fund state parks and historic sites. Among other books about parks advocacy, he wrote "Texas State Parks: The First 100 Years, 1923-2023."

Jennifer Bristol, who helped shape youth programs at the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department for years, is the author of two popular recent books, "Parking Lot Birding" and "Cemetery Birding." She contributed a chapter to her father's state parks history and is working closely with her mother on the book about women in conservation.

In a possible father-daughter first, George and Jennifer will be featured at this year's Texas Book Festival, scheduled for Nov. 11-12 in and around the State Capitol.

Jennifer will appear alongside biodiversity expert David M. Hillis ("Armadillos to Ziziphus: A Naturalist in the Texas Hill Country") at 10:30 a.m. Nov. 12 in Capitol Extension Room E2.014. George will speak in tandem with Andrew Sansom ("The Art of Texas State Parks: A Centennial Celebration, 1923–2023") at 3 p.m. Nov. 12 in the same room.

"It's getting to be a family tradition," George says. Another offspring, Mark, lives in Dripping Springs. Mark's outdoorsy children, Evelyn and Walter, earned Eagle Scout badges; Evelyn was among the first group of girls nationwide to do so. "We love the outdoors. We love nature. We love parks and conservation."

'Parks are where people go': A father's story of politics and parks

George Bristol was born in 1941 in Denton. His father died in 1946. His mother, a schoolteacher and librarian, didn't have a car.

So the opportunity to work at Glacier National Park in Montana during the summers of 1961 and 1962 was a godsend for a young man from North Central Texas who spent as much time out of doors as possible.

"It's in my DNA," George says before half joking: "I eventually bought some resort hotels in Montana, primarily for my growing family and friends. If any rooms were left, I opened them up to the public."

Political contacts came early, too. While growing up in Weatherford, he got to know Jim Wright, mayor from 1950 to 1954. Wright later rose to be Speaker of the U.S. House. His onetime suite mate was Stewart Udall, one of the leading figures in the national conservation movement and later secretary of the interior under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson.

As he rose behind the scenes in political life, Bristol played ongoing roles in the funding of state and national parks. In 2012, he wrote "On Politics and Parks," which reveals the complicated political machinery behind the parks movement in the U.S. and Texas.

"Somebody asked: 'Why don't you do a centennial book on Texas parks?'" George says of his latest book project. "The pandemic broke out, so all I could do is write, read and research. I couldn't do justice to the roles of women in that history or the role of the Civilian Conservation Corps, so I asked Jennifer to do a chapter on the first, and Cynthia Brandimarte, one of the authorities on the CCC, to do the second."

More: Texas Book Festival set to honor novelist Elizabeth Crook with the 2023 Texas Writer Award

In May, I wrote about George Bristol's centennial volume: "This is a biggish book. It includes a full section with glorious photographs of each state park, along with appendices on the sporting-goods-tax campaign and other background material."

One of the lucky research finds was a packet of personal letters and documents related to political activist Marian Powell and the parks movement. She got the legislature to accept the land donated for the first state parks, including a bequest from Isabella Eleanor Neff, mother of Gov. Pat Neff, who appointed the first state parks board in 1923. That bequest became the foothold for Mother Neff State Park, the first park in the state system.

"The women's clubs of Texas acted side by side with the government structure to build the parks system," Jennifer says. "They could get out the vote. They didn't have any direct power or authority, but the clubs, on any social issue, formed committees that were very organized. They ended by saying: 'This is what we are going to do.'"

This trend happened at the national level, too.

"Stephen Mather, the first superintendent of National Parks in 1916, turned to the women," George says. "There were 250,000 women in the clubs. President Woodrow Wilson signed the bill that they wanted. And in Texas, they gave Gov. Neff an additional push. He knew he had to have them."

"There were 50,000 members of women's clubs in Texas alone," Jennifer says. "In every Texas town, there was a head woman. They were useful political allies."

As for the 2019 amendment that secured basic funding for state parks, George Bristol is quick to point out that it was not a new tax. It simply stopped legislators from raiding the money originally intended for parks.

"Parks didn't have advocates," he says of the fight from 2001 to 2019 for tax dedication. "They didn't have guaranteed funding. But parks are where people go. All the stars aligned, and politicians were tired of getting beat up in the press. The media got behind it. All the groups got behind it. It won by 88% of the vote.

"And it made sense to join the historic sites with the natural ones. You can't separate the urge to conserve with the urge to preserve."

In fact, periodic polls for the past two decades have regularly shown that 75% to 80% of the public love parks and want money intended for parks to go to parks.

On Nov. 7, the public will be asked to approve an amendment to secure a $1 billion permanent fund to buy and improve new state parklands, not with a new tax, but with a slice of this year's unprecedented budget surplus.

"I'm very confident about the vote in November," George says. "People understand and appreciate parks. If you don't believe me, try to shut one down."

'Sweet nexus of habitat and history': A daughter's guides to birding in unexpected places

In 2019, Jennifer Bristol stepped down from her longtime role at Texas Parks and Wildlife in part to work on the books her parents were writing. Yet she also branched out on solo projects. The first, "Parking Lot Birding," not only attracted nature newbies intimidated by high-adventure birding, but it also fit into widespread efforts to make outdoor activities accessible to the mobility impaired.

On a personal level, Bristol and her book helped me out tremendously when I put together a newspaper guide to the best birding spots in Central Texas.

More: Calling all birders: Here are the 12 best bird-watching spots in Central Texas

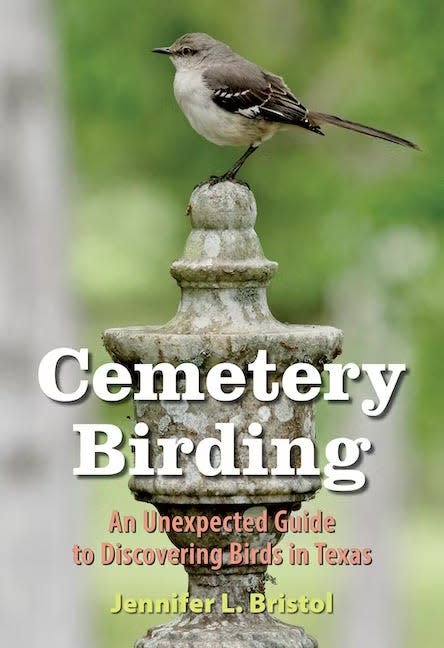

The sequel, "Cemetery Birding," which covers the natural and historical aspects of Texas graveyards, was made possible in part by the pandemic.

"Starting in spring 2020, I'd load up the van before dawn," she says. "Gas was $1.25 a gallon. There was no traffic. I learned the histories of the places through the end of 2022."

She updated her personal sightings with online information from others birders, through a combination of what was reported on eBird.org and what "verifiers" approved as birding "hot spots."

Some cemeteries were situated next to parks, which made the mechanics of parking and camping easier. Plus, the two kinds of sites often hosted similar environments.

"I was seeking that sweet nexus of habitat and history," she says. "Not all cemeteries have both. Some are designed to be flat and mowed, others are over-sprayed for what birds actually eat."

She found one particularly thoughtful Texas cemetery in Rockport.

"It's planted with wildflowers that change from March through June," she says. "There's a beautiful mix of colors, and letting the flowers grow cuts back on the need for mowing."

In spring, the historic Oakwood Cemetery in Austin goes wild with bluebonnets.

"You stand in front of a sea of blue set against all that white stone," Jennifer says. "Insects love it, and birds love the insects. I hope more cemeteries let the wildflowers bloom."

A gifted wildlife photographer, she took all the pictures in "Cemetery Birding," which is usefully divided into regions through color coding and handy maps. The book jacket shows a mockingbird, the Texas state bird, perched alertly on a weather-stained memorial.

The first cover design proposed by the publisher depicted a house sparrow, not a native to Texas.

"I can't put a house sparrow on the cover," she jokes. "I'd be laughed out of the birding community."

Michael Barnes writes about the people, places, culture and history of Austin and Texas. He can be reached at mbarnes@gannett.com. Sign up for the free weekly digital newsletter, Think, Texas, at statesman.com/newsletters, or at the newsletter page of your local USA Today Network paper.

Texas Book Festival

When: 11 a.m.-5 p.m. Nov. 11, 10 a.m. 5 p.m. Nov. 12

Where: Inside and around the Texas Capitol at 11th Street and Congress Avenue, with select additional venues

Cost: Free, with select ticketed events

Information: www.texasbookfestival.org

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Father-daughter nature authors a first for the Texas Book Festival