Out of Our Past: Centerville man displayed strength to fulfill a friend's final request

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Dec. 6 in history:

In 1790, the U.S. Congress moved from New York City to Philadelphia.

In 1884, the Washington Monument in Washington, D.C., was completed.

In 1933, U.S. federal judge John M. Woolsey ruled that James Joyce's novel "Ulysses" was not obscene.

In 1967, Adrian Kantrowitz performed the first human heart transplant in the United States.

On Dec. 6, 1822, a “contrary and irrepressible” local Wayne County Revolutionary War veteran sought to fulfill the last request of a friend sentenced to die.

To do this he had to physically oppose the will of a mob of people and retrieve the body after a hanging.

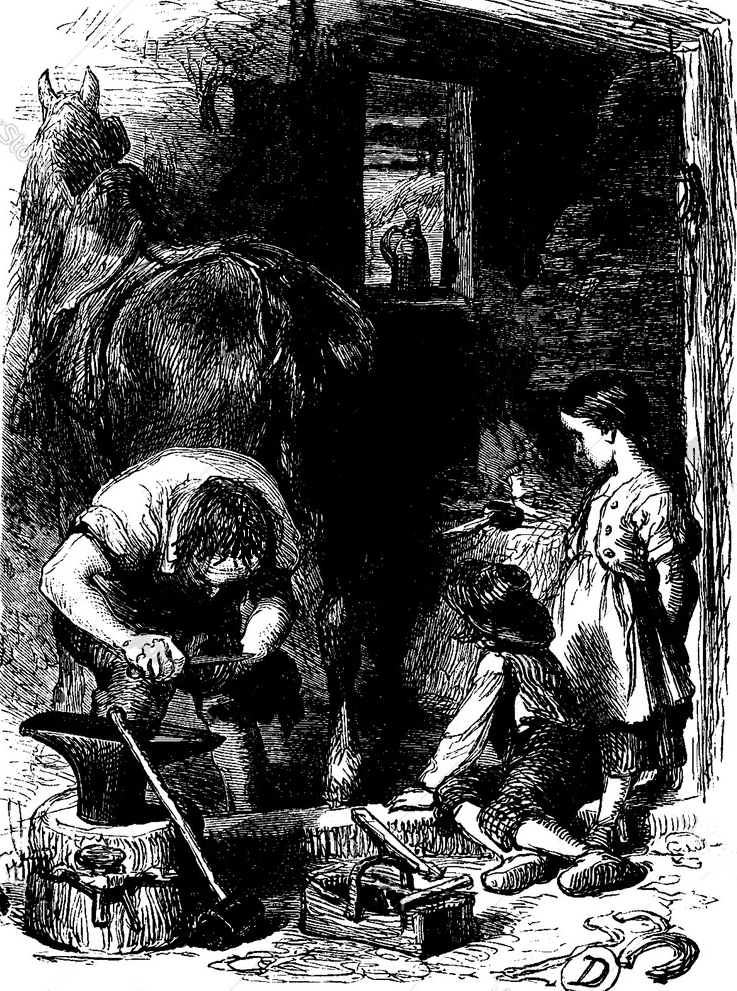

According to the ‘History of Wayne County, Indiana (1872),’ Revolutionary War veteran Christopher Roddy was a blacksmith who bought the first lot in Centerville after it was platted on Oct. 20, 1814. Intending to locate his blacksmith shop there, he proclaimed it his honor to name the place, which he promptly did.

Roddy had lived in the (now-extinct) town of Salisbury, and since this new town where his blacksmith shop was to be located was an estimated three miles nearer the geographical center of the county, he dubbed it Centreville.

More Out of Our Past: Young Richmond pilot walked away from a plane crash in 1963

Roddy, a non-commissioned officer who had fought all seven years in the American Revolution, was known “as a brick, a man who could drink more whiskey, swear more wickedly, fight harder and oftener, and do more deeds of daring than any other man in the Whitewater Valley.” He was considered “honest, hardened in sin, well-versed in profanity and intemperance of whisky, capable of enduring a great amount of fatigue… far removed from cowardice, and never known to quail before an enemy or danger.” He had at one time been a man of faith, but no longer. He had come to Wayne County in 1810, and for all his faults, it was said he “always accomplished what he undertook and was never known to go back on a friend.”

Such was the case when a Black man named Hampshire Pitts, who had been sentenced to death for murder, asked the impossible of him.

Pitts had stabbed a man to death in a quarrel over a woman and was sentenced by a jury “of good and lawful men and discreet householders” to be hanged near Centerville on Dec. 6, 1822.

The court decreed: “It is considered by the court that said Hampshire Pitts be taken from the bar of the court to the gaol (jailhouse) of the said county; thence on Friday, the 6th day of December next, between the hours of 11 o’clock and 4 o’clock afternoon of the same day, to a place of execution, and there be hanged by the neck until he be dead.”

Pits met the sentence with grim fortitude, and arranged for a compatriot to take possession of his body after the execution. But the man instead sold the doomed man’s body to physicians intent to use it for dissection.

Upon learning two physicians had purchased his corpse for $10 to be “butchered up,” Hamshire Pitts became horrified. He pleaded with Christopher Roddy to hide his body after the execution.

Roddy agreed to bury the body where no one could find it.

The day of the execution was cold, cloudy and disagreeable. The ground was covered with four inches of snow. Centerville was thronged with citizenry to witness the execution of the murderer. About 11 a.m. Pitts was taken from the prison to the courthouse where a sermon was read.

According to accounts, “The doomed man was sequestered in an open wagon, seated upon his coffin, heading to the gallows, which was erected in the suburbs in the northeastern portion of the village, the site of the execution crowded full of men, women and children, bent on viewing the horrible spectacle.”

The physicians were on hand with a wagon.

Christopher Roddy arrived with a sled.

According to witnesses, “As no platform had been erected, the prisoner, Sheriff Samuel Hanna and a few assistants stood in the open wagon under the gallows, while Pitts made a short address and took leave of his friends.

“He warned all present to govern their passions, and never let their evil temper plunge them into crime. He was very deeply penitent, and said his doom was a just one.

“Pitts thence stood upon a cart while the rope was fastened around his neck and the vehicle was driven out from under him. He was strangled slowly after the fashion then in vogue. His agony may be judged by the fact that it was sixteen minutes after he was swung off before life was pronounced extinct… After hanging some 30 or 40 minutes he was cut down by the sheriff and placed in a plain coffin under the gallows. At this point, three or four sons of the Aesculapians (doctors) sprang in and seized the coffin and were about to hurry it into a carriage that stood there waiting for the corpse which they desired to secure for dissection. Roddy and two physicians seized upon the body and a very long and hard struggle ensued. The dissectors being baffled in their purpose by Christopher Roddy, who enjoined the crowd with an axe drawn, swore that he would make mince meat of the doctors if they did not drop the corpse, which they immediately did, and craw-fished from there. Roddy had shed blood in war and was willing to shed it again. The physicians knew this and withdrew. Aware of Roddy’s fighting abilities and staying qualities made the medical men conclude discretion was the better part of their valor.

“Roddy placed the coffin upon a sled and conveyed the corpse to his home in Salisbury, where he guarded it throughout the night. Later he secreted it on his shoulders to be discreetly buried in the teeming wild. In the dead of the cold winter night… he threw the frozen corpse on his shoulder and strode away to the dense forest. Occasionally he sat the mortal part of Hampshire Pitt up against a tree, wiped the frost from his brow, took a long swig at a black bottle of corn liquor, picked up his burden, and marched on. Beside the body he carried a shovel. His progress was slow and tiresome. Finally, seven miles from where he started, in a lonely and thickly shaded spot, he dug a shallow grave and laid the poor dead form to rest. He covered it over with dirt and, piled brush on the spot and left it there safe from the hands of grave robbers.

“The next day he cut down all trees close enough to fall on the grave, and left it under a mass of timber.”

Ravenous animals never got to it — and neither did the physicians.

Christopher Roddy lived his life out in Wayne County and, like his hanged friend, there is no record of where he is buried.

“Although it is not clear where his unmarked gravesite is, it is clear the man’s deeds live after him.”

Notes: This story was put together using the first person account of Sanford C. Cox in his memoirs, Andrew Young’s ‘History of Wayne County, Indiana [1872],’ the Feb. 7, 1882 Richmond Item, the Aug. 6, 1886 Richmond Evening Item, the Oct. 2, 1882 Richmond Item, and Judge Henry C. Fox’s narrative in the Nov. 16, 1907 Richmond Item.

Contact columnist Steve Martin at stephenmonroemartin@gmail.com.

This article originally appeared on Richmond Palladium-Item: Out of Our Past: Centerville man fulfilled a friend's final request