Past experiences made Judge Waite a 'quiet witness and warrior' in the Civil Rights era

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Clyde Waite watched the black boots of Alabama State Troopers approach the overturned pickup stuck in a swamp after they ran it off the road. Trapped in the truck bed, the then 22-year-old college student did everything in his power to stay invisible.

Civil Rights activists warned Waite and the other students from Howard University, a historically black college, about the dangers facing people in the South registering Black voters in 1965.

“But I didn’t fully appreciate it,” the 78-year-old Waite said recently from his home in Wrightstown. “At that age, you’re kind of idealistic. You kind of feel like you’re on a religious pilgrimage.”

The story of the Civil Rights-era trip to Selma, Alabama is one that Rev. David Perkins had not heard about Waite, a member of the Pebble Hill Church, before asking him to speak at this year’s Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. service at the Doylestown Township interfaith church.

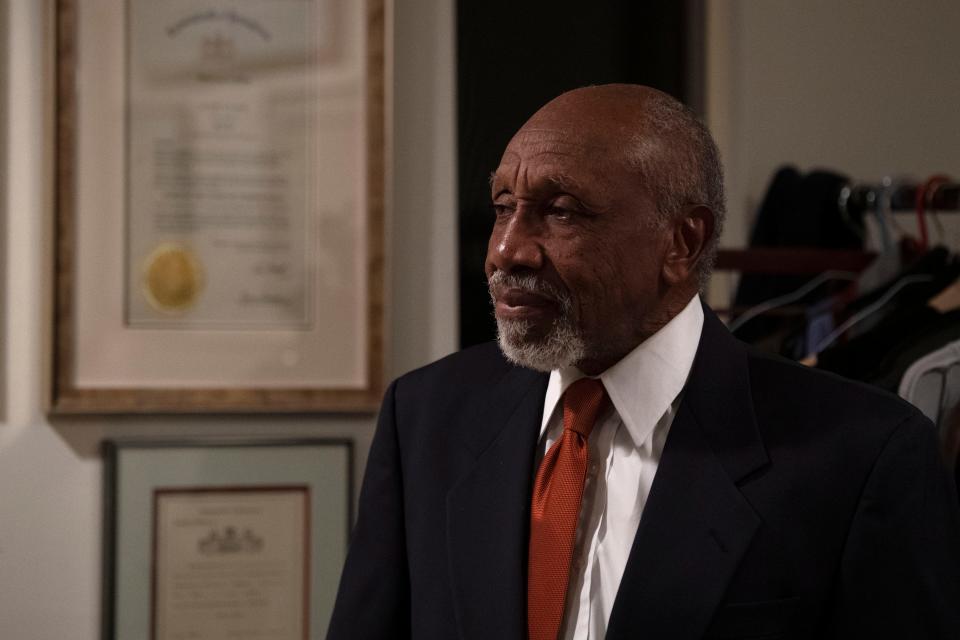

But Perkins had heard other stories about Waite's experiences during the more than 50 years he has lived in the predominately white county where until last month Waite was the first Black judge, and only, to serve in Bucks County Common Pleas Court.

“I know enough that I know I wanted him to come speak,” Perkins said. “In his own way he has been a quiet witness and warrior for social justice, positive social change and inclusion his entire life.”

Recently Waite recounted his experiences as a Black man during the civil rights movement in first Washington D.C. then the campus of Yale University in Connecticut during one of the most transformative and historic periods in U.S. history.

How you can celebrate MLK Day this yearWays to celebrate and honor Martin Luther King's legacy in Bucks and Montgomery counties

How typing and shorthand changed Clyde Waite's life

The day after his 1962 high school graduation ceremony, Waite packed his belongings into a suitcase secured with a piece of rope and bought a train ticket to Washington D.C. where he knew no one.

His secretarial skills and a high score on the civil service exam landed him a conditional job offer at the Library of Congress. After a second skill test Waite was hired on the spot.

“I couldn’t wait to get out of McKeesport,” he said of his western Pennsylvania hometown in Allegheny County, outside of Pittsburgh. “Any job was considered a good job.”

College was the furthest thing from his mind, until several months later when Waite was out looking for an apartment. He passed a building where outside he saw the most beautiful women he had ever seen.

It turned out he stumbled upon the girl’s dormitory for Howard University. After learning more about the college, he decided to fill out an application.

While high school prepared him for a government job, he lacked the knowledge necessary for the rigors of college curriculum. Howard rejected him.

But Waite is no quitter. He took college prep classes at night school. In 1964, after submitting his third application, he was allowed to enroll in Howard on a probationary basis. His first semester he maintained a “C” average and earned a spot in the Class of 1968. For the rest of his college career he made As and Bs, while working fulltime.

Those early years living in the nation's capital Waite described as an electric time. Something was always happening.

If there wasn’t a demonstration in front of the Supreme Court building, there was one at the Capitol or a march down Pennsylvania Avenue. The Civil Rights movement and efforts to overturn segregation in the South was gaining traction nationally and Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was making a name for himself as one of its leaders.

But King's name was not one Waite was aware of before entering Howard University. He was more familiar with Elijah Muhammad, the leader of the Nation of Islam, a militant civil rights group that was critical of King.

He was in his second year at Howard In 1965, when the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was recruiting students to register Black voters in southern states.

Waite signed up for a two-week recruiting drive in Selma, Alabama. He had been registered to vote since his 18th birthday and knew its value for racial minorities.

“I felt I was obliged to do something even though it was something I knew was dangerous,” Waite said. “I really didn’t know how vulnerable and exposed I would feel until I’m there, recognizing that the authorities would not protect you. You had no protection from anyone.”

How a trip down South strengthened the character of a young Black man

The SNCC headquarters in Selma was across the street from the police station, an intentional location so police could not say they were not aware if violence erupted, Waite said.

Volunteers like Waite were warned not to carry sharpened pencils since they could be seen as weapons and result in an arrest. He remembers how the sheriff met the bus when it pulled into Selma and the 40 students aboard were all searched.

Outside, a few SNCC workers from the area met the bus, but they were far outnumbered by the hundreds of segregation supporters who surrounded them.

“It was something that was expected, but still shocking because you can expect something but you don’t know how psychological and emotionally vulnerable you would feel when it actually happened,” Waite said.

During the Selma trip, Waite and others were put up by people sympathetic to their cause who risked their jobs, and lives, housing the students. It’s why they never stayed in the same place twice.

“I remember being in one of these shanty-type houses built on stilts, and a trap door,” Waite said. “If someone came to the front door, you could go through the trap door and escape under the house.”

Every day, Waite and others left the SNCC headquarters in Selma and traveled 28 miles to rural Lowndes County, where 80% of the residents were Black and not one registered to vote, Waite said. The trips were made either before sun up or after sun down, when they knew farmers would be home.

The town was known as "Bloody Lowndes” because of the high number of Black citizens who died by lynching.

About halfway through the trip, Waite started sleeping at the SNCC offices after a disturbing incident at the home of a Black farmer.

Waite was among a group of volunteers who were meeting at the home, when the headlights from a caravan of cars headed up the driveway. The homeowner pulled out his shotgun and loaded it with three rounds as the caravan drew closer.

The abduction and murders of three young Civil Rights volunteers registering Black voters in Philadelphia, Mississippi, not even a year earlier was still a fresh memory.

“We were quite frightened,” Waite said.

The visitors turned out to be other SNCC members, but the experience was a prelude for a confrontation a few days later.

Before sunrise, Waite was among five volunteers in a pickup truck headed to Lowndes. The driver, a man, and three women squeezed into the cab and Waite tucked himself into a sleeping bag in the bed of the truck. At some point in the ride, he felt the pickup speed up. Then he heard sirens.

He felt the truck travel off the paved road onto the wet grass where it fishtailed, flipped over and slid down a hill into a swamp.

Waite was trapped in the overturned bed, but he could see what was happening through a gap. He had no idea if anyone was hurt, or what the troopers planned to do.

“I was terrified,” Waite said.

The driver was arrested on a charge of “defacing the highways” and hauled off to jail in Selma. The three girls in the cab were not seriously hurt, but left behind.

After Waite dug himself from under the truck, the four walked until they found a Black farmer with a tractor. The farmer drove them back to the pickup, up righted and hauled it back to the road.

One wheel was badly bent, but the vehicle started up. Waite was the only one with a driver’s license, but he didn’t know how to drive a stick shift. Somehow, they made their way back to the SNCC office, where they then went across the street to see about bailing out the driver.

The rest of the trip was uneventful, Waite recalled. Though before he and others returned to Howard University, Rev. King visited the SNCC office, shook their hands and thanked them for their efforts.

How the assassination of MLK led to a Yale Law School acceptance

While Waite admired King’s commitment to end segregation, he was not enamored with his philosophy of nonviolence.

“It didn’t feel right that you’re going to advance by letting someone beat you over the head," he said. “I feel either I'm going to wear a helmet, if someone is going to try and beat me over the head, or I’m going to try and push them away or something, I feel I have to take matters into my own hands.”

On the other hand, Waite also disagreed with the approach of Nation of Islam and Black Panthers, who he considered activists who made a lot of noise, but did not put their lives on the line for equality.

“I was somewhere in the middle where I wanted to be active, but not destructive,” Waite said. “I would not want to participate in the actions of people bent on anarchy and chaos. I’m more inclined to try and build bridges.”

His experience living through the Civil Rights movement and the D.C. riots shaped his decision to pursue a law career. He applied to a number of law schools, but did not hear from most of them.

Until five days after the King assassination in Memphis, Tennessee.

A letter from Yale Law School arrived. It said while the openings for the Class of 1971 had been filled, due to the “extraordinary circumstances” Waite was on a wait list.

A month later a Western Union telegram arrived telling Waite he got in. He was one of 12 Black students accepted, the largest number of Black law students in Yale’s history at that point.

To this day, Waite believes King’s death influenced his admission.

“I know damn right well I never would have gotten into Yale if it wasn’t for the assassination of Martin Luther King,” he said. “No way.”

After graduating from Yale, Waite and his first wife moved to Bucks County in 1971 where he volunteered with the Legal Aid Society and worked part-time as a public defender.

His experiences as a Black man living in a predominantly white suburban community opened his eyes further about how racial minorities were viewed, he said.

Waite had saved enough money to buy a house, but no realtors would show him houses in the Central Bucks area. It was the member of the Pebble Hill Church, which Waite and his wife had joined, who helped connect him with a realtor who agreed to work with him.

He bought a small home on Swamp Road near the Moravian Tile Works without going to see it first.

“It’s a house, it has four walls, I’ll take it,” Waite said.

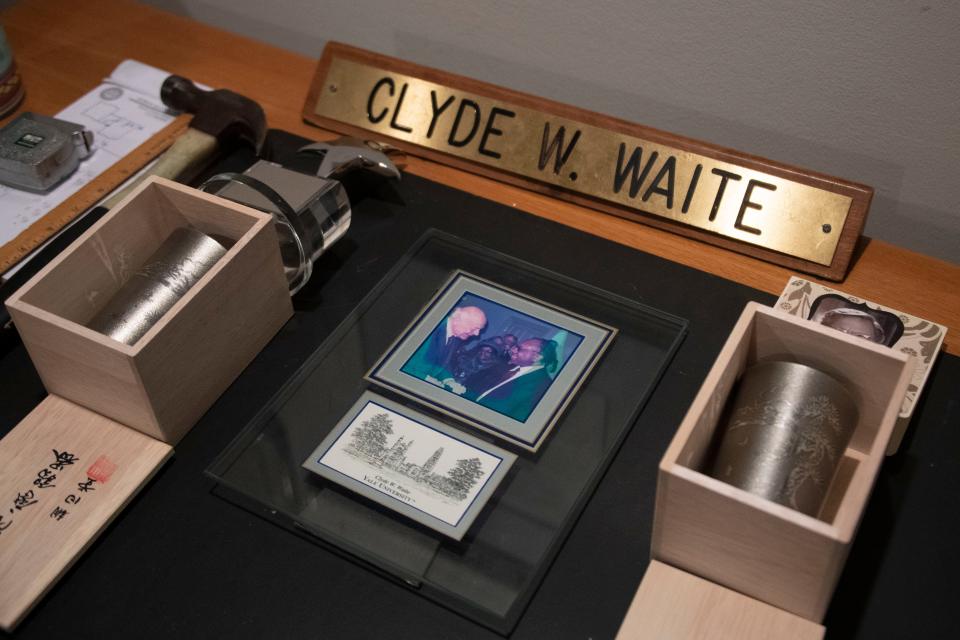

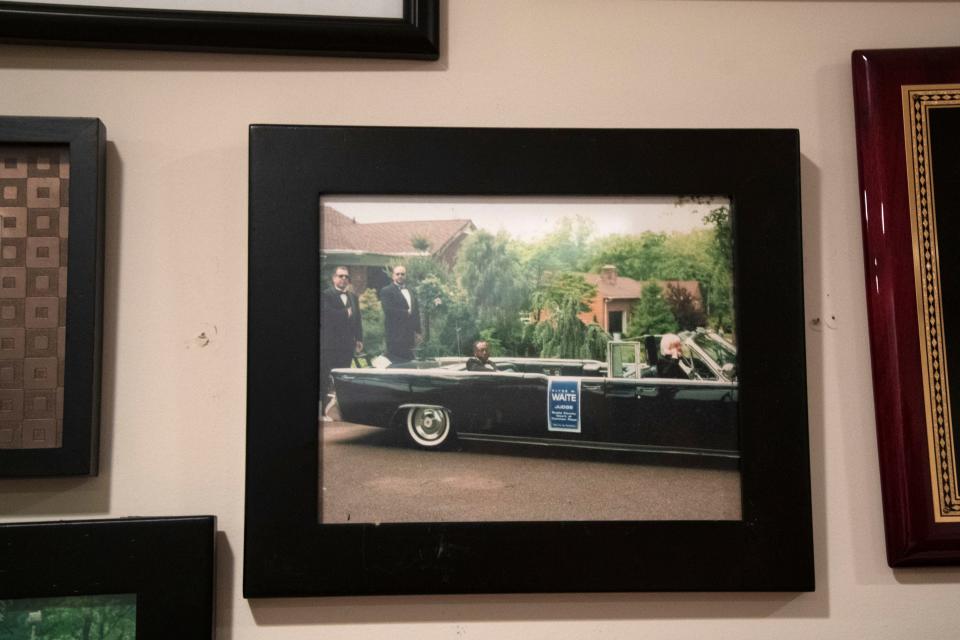

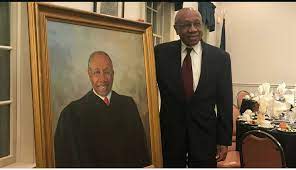

As a Bucks County resident, Waite developed a reputation as a successful lawyer, real estate developer and community activist, which culminated in his 2003 election to the Bucks County Common Pleas Court.

He remains the only Black judge in Bucks County history.

Where are the Black judges? 'Literally zero representation': Few Black women serve on U.S. courts, none on Bucks County bench

Despite a prominent career in the county, Waite said he still bumped against the occasional reminder of his outsider status.

Once he was mistaken for a waiter after he attended what was billed as a black-tie Bucks County Bar Association event dressed in a tuxedo. Early in his legal career in the county a judge mistook him for a criminal defendant in court.

After winning his re-election in 2013, Waite was gathering up his campaign signs outside the Doylestown courthouse when he was mistaken for a janitor.

A guest staying at a neighbor’s home during Thanksgiving weekend in 2016 called police after seeing a black man walk into the home at night. Police, who knew the judge lived there, surrounded the home and demanded the person inside come out.

His hand raised, Waite walked out and asked the officers what was going on. One officer immediately recognized Waite as a judge and told him that they got a call about a home invasion, breaking glass and a commotion.

Waite let the police inside to look around, but they found no one else. Later, he found out what happened was a case of mistaken identity.

“The neighbors told (the house guest) that a judge lived next door and when they saw me, they didn’t see what a judge looks like,” Waite said. “A judge doesn’t look like me.”

He can laugh about the situation now. At the time, Waite said he was more confused about the police presence than frightened by it. He insists he never held ill feelings toward anyone involved.

Waite explained that he has come to accept that people, himself included, hold unconscious bias and judgments about others based on superficial traits and people are more comfortable around what is familiar to them.

“Your feelings are feelings. You can’t consciously be, I’m not going to feel this. If you feel it, it’s there,” he said.

What is important, Waite believes, is that people recognize and acknowledge bias exists, and find a way to manage it.

“The reason the U.S. is one of the greatest countries is because of the mixture of all different races, religions, energies, talents. No one has all the assets, and everyone has some assets,” he said. “You cannot require a one-legged person to run a 100-yard dash in 10-seconds, but you can have that one-legged person strategizing for that able-bodied person to do the best they can do.”

Former Bucks County Common Pleas Judge Clyde Waite will be the guest speaker Sunday at the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. celebration service at Pebble Hill Church. The interfaith service starts at 10:30 a.m. and it is open to the public. The church is located at 3230 Edison-Furlong Road in Doylestown Township. The service is available online through Zoom by clicking on this link. Meeting ID is 85886792229 passcode: &ZuE3J

A case of mistaken identity His hands up, a county judge is rousted from bed at 1 a.m.

Another Bucks County judge is retiringBucks County Judge Diane Gibbons is retiring. Here's why she'll be back on the bench soon

This article originally appeared on Bucks County Courier Times: Bucks County Judge was on frontline of Civil Rights movement