Past and present converge at Lick Creek settlement, Buffalo Springs restoration project

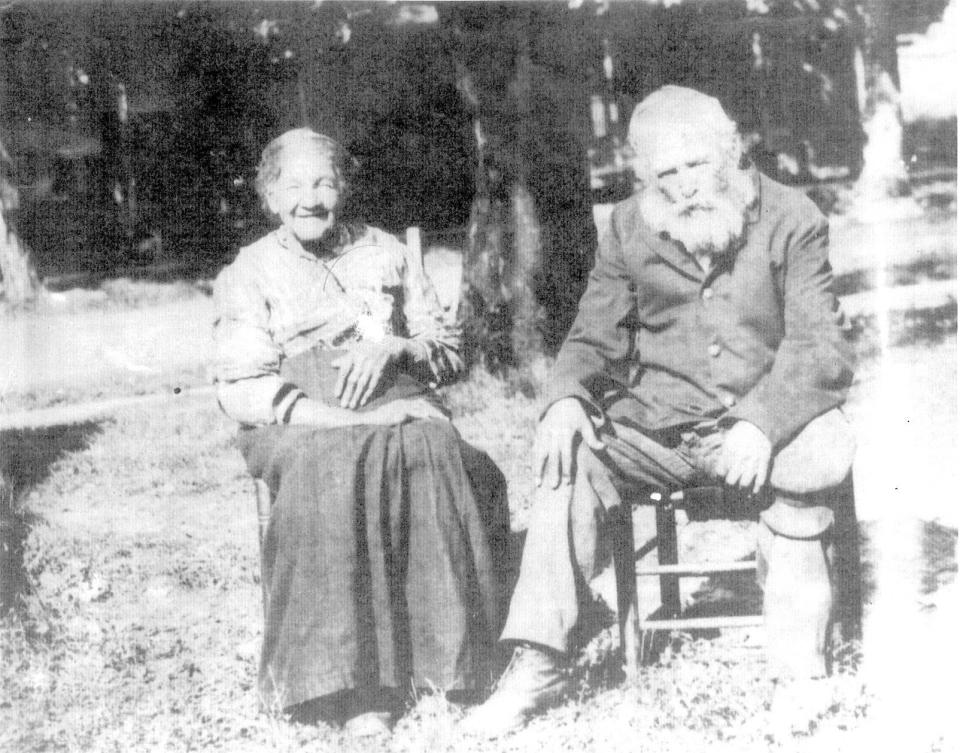

At 78 years old, Diana Daniels looks back on a life spent studying the past. Long threads unwound over decades reveal to her a rich family history, one that speaks to the pursuit of freedom and happiness as a Black American in the 1800s.

For Daniels and other descendants of Indiana's early Black settlers, the Lick Creek African American Settlement in the Hoosier National Forest, which dates back to 1811, contains important history. To forest advocates, the Buffalo Springs Restoration Project seems to threaten that land in Orange County.

Daniels' knowledge of her own history began with storytelling.

As a little girl, Daniels learned who she was as so many others do: through bedtime stories and family lore; from the twinkle in her grandfather’s eye and the whisper of magic in his words.

She heard tales of “Little Africa,” a place where her ancestors cultivated the land and built churches, where they grew their families. It was a far-off place in her mind, one separated from her by land and sea and centuries gone by.

Only as an adult did she realize Little Africa was 20 minutes down the road.

Nestled in Orange County, not half an hour from Daniels’ hometown of Mitchell, Indiana, are the echoes of a settlement where, at one time, nearly 300 free Black Americans lived.

Lick Creek settlement and the Buffalo Trace

In 1811, slavery was legal. Crossing the country entailed weeks of paranoia, starvation and danger. For African Americans, coming to Indiana presented untold peril.

They came anyway.

Alongside sympathetic Quakers, Black Americans who had escaped slavery voyaged to an area of Indiana now known as Orange County. They and their descendants resided for nearly 100 years at the Lick Creek African American Settlement.

Happening Tuesday: History of Lick Creek settlement for African Americans to be presented by Forest Service

It lies along the Buffalo Trace, a centuries-old route created by bison and used by pioneers to navigate uncharted territories.

The Hoosier National Forest and Indiana State Museum have conducted field studies at the settlement throughout the past 20 years. Researchers unearthed artifacts from the 1800s, including tobacco pipe fragments and cup plates, from farmsteads and home sites. Some items are on temporary display at the Orange County Historical Society Museum in Paoli.

Annual gatherings at Lick Creek settlement

The area, at first glance, looks like much of Indiana's forested land: sycamores with mottled bark, sunlight filtering through clustered leaves, tree limbs winding through the open sky.

A trail stretches through the woods. At first, there isn’t much to see.

But follow the trail to its end, and you’ll find relics — rectangles of moss-draped limestone engraved with names and dates — in the cemetery. It contains 14 marked graves, but many others lie beneath the grass and dirt. It is officially known as Roberts and Thomas Family Cemetery.

The cemetery is named for two of the settlement’s founding families. Daniels said she discovered her connection to them through her maiden name, Bonds. Her ancestors married into the Roberts family.

Together, the families of Lick Creek descendants walk the trail once a year. In 2023, more than 30 of them stood among the gravestones.

This is where we come from. This is who came before us.

They decorated the graves with polyester flowers. They prayed. They honored the ancestors they never met, but who risked their lives for the freedom this place promised.

And they wondered what its future might hold.

It isn't in the books. It's in our families.

At this year’s reunion, Daniels felt weariness trickle into her muscles as she trekked to the cemetery. Her joints ached. She wondered again whether future generations would make the trip.

Nearing 80 years old, Daniels watched as her fellow descendants shared her struggles. They’d like to have a wooden staircase, at least, she said, to make these trips easier.

For younger generations, the biggest hurdle is sparking interest, said Daniels, who serves as the executive director of the Indiana Council on Educating Students of Color. She’s got a few ideas to make Lick Creek more welcoming. Adding placards with information about the area along the trail, building a model of the settlement’s church and restoring the graveyard are some of them.

“That’s too much history to just let go,” Daniels said. “I’ve got to fight for that.”

Last year, she reached out to the Black Heritage Preservation Program, which provides grants to Indiana sites of African American history. The program is part of Indiana Landmarks, the country’s largest statewide preservation organization.

Celebrated musician: Pianist and IU Jacobs School of Music professor André Watts dies at 77

The Black Heritage Preservation Program's grants are funded by the Lilly Endowment. The program has about $200,000 each year to spread statewide for various preservation and restoration projects, Director Eunice Trotter said. If Lick Creek descendants apply for funding, they might be able to make the historic site more accessible and informative.

Not enough people know the story, Daniels said.

“I taught U.S. history,” she said. “I never knew any of this. It isn’t in the books. It’s in our families.”

Buffalo Springs: Where past and future clash

Debate has raged since 2021, when the public was first informed of the U.S. Forest Service’s proposed Buffalo Springs Restoration Project. The project addresses over 5,000 acres of the Hoosier National Forest, primarily within Orange County.

Through prescribed burns and vegetation treatments, the Forest Service plans to keep the forest diverse and healthy, said heritage program manager Tesa Villalobos. The oak-hickory community in the Hoosier National Forest has been crowded out by non-native pines. Long-term, this means the forest could fail to support wildlife and lose tree species crucial to the ecosystem, she said.

The Lick Creek Settlement, sprawling over 1,500 acres, falls within the project’s boundaries. Some community members are concerned that forest management will destroy the Buffalo Trace's history with fire, pesticide treatments and logging, said Steven Stewart of the Indiana Forest Alliance.

But prescribed burns are the only treatment proposed for the Lick Creek area, and many segments of the forest won't be affected at all. The Forest Service has not yet confirmed which segments will be treated.

The Buffalo Springs project is now in the final environmental assessment stage. There will be a public comment period this fall once the assessment is completed, said Marion Mason, Hoosier National Forest spokesperson.

Things to do this weekend: Keep out of the heat: Barbie, Oppenheimer, Shrek and an SNL comedian in Bloomington

And, if approved, prescribed burns will gnaw away at unnecessary low vegetation, promoting new growth, Villalobos said.

The burns, low-intensity and controlled, will not disturb the cemetery or underground excavated sites, like those where the church, the union meeting house or the 13 farmsteads once were. By surveying the land, the Forest Service can determine areas with historical and cultural significance.

Hoosier National Forest follows the National Historic Preservation Act. So though the forest around and within Lick Creek Settlement may face burns, the underground artifacts and cemetery will be preserved.

Being added to the National Register of Historic Places would provide the sites with another layer of protection, Villalobos said, and it might aid in restoration efforts.

The Indiana Forest Alliance and Indiana Landmarks collaboratively advocate for the Buffalo Trace. According to Stewart, some of their goals include:

Buffalo Trace cultural center and museum

Genealogy archive and library

Interactive ArcGIS map and website

Nature preserve and recreation area

The Forest Service, Indiana Landmarks, Lick Creek descendants, and Indiana Forest Alliance are just some of the parties with an interest in giving the settlement an official designation as a historic site. Whether by burning away non-native species or building staircases and adding signage, they have a common interest: preserving the history of the Lick Creek African American Settlement.

This article originally appeared on The Herald-Times: Future of Little Africa settlement in Hoosier National Forest