Paterson’s Pat Kramer was a visionary who saw majesty through a watery lens

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

A long, long time ago, when the Paterson mayor was young and I was even younger, I remember questioning his reverence for a certain waterfall.

“It’s just falling water,” I said. “What’s the big deal?”

In less time than it takes to walk a dog to a hydrant, Pat Kramer drove me to an unkempt park and coaxed me to join him on a slippery, 2-foot-wide grassy ledge where we stood face-to-face with the Great Falls as it hurled the Passaic River into a rocky gorge. While spray spattered our jackets and ties (yes, we wore suits in 1967), all that kept us from plunging 77 feet into the polluted river below was our death grip on the cyclone fence behind us.

“This is how you see my falls!” Kramer shouted above the roaring cascade. “You can’t appreciate their majesty from the parking lot!”

Lawrence Francis Kramer, who died last month at age 90, spent a lifetime persuading us to hold tight and open our eyes to the possibilities as he saw them — regardless of the noise, the danger or the odds.

The right man at the right time for Paterson

It was a message that resonated in the mid-1960s.

Few cared then about the hydropower landmark that inspired Alexander Hamilton to found the nation’s first industrial city. Industry was dying in the Silk City. Like hundreds of American urban centers, New Jersey’s third-largest city was losing jobs and shoppers to the suburbs. The local exodus was hastened by a 4th Ward riot, which in turn fueled distrust in the city’s nearly all-white police force. Construction had even been halted on Interstate 80 because locals complained that plans didn’t call for downtown ramps.

So in 1966, Paterson voted to assign the unenviable task of curing these ills to its youngest mayor — a 33-year-old father of two (at the time) who had left school to run his late father’s brickyard business. As voters saw it, a brief stint on the local school board was enough to train a Republican college dropout to run the Democratic stronghold that its bullying, law-and-order Mayor Frank X. Graves Jr. had dominated until term limits forced him to leave office.

Some pundits were sure Graves would rout this upstart in the next election. But Kramer, who had overcome polio at age 7, had long ago learned lessons about teamwork and persistence by playing ball on local fields and working for the March of Dimes. The new mayor would win three more elections, including a thrashing of Graves, that eventually secured lasting recognition for his city — both for its value as the birthplace of American industry and as a persistent reminder of how much can be achieved with consistent leadership, a little flair and a big waterfall.

“Pat’s probably the best politician I ever met, and I’ve met a bunch,” said Rep. Bill Pascrell Jr., D-Paterson, himself a former mayor who began his government career as a Kramer aide before winning 14 terms in Congress. “He’d walk into a gloomy room and cheer everybody up. He had a good word for everybody.”

Whether he was persuading doubters or jousting with presidents, Kramer’s energetic mix of hyperbole, humor and chutzpah earned him thousands of friends — a quality probably passed on to him by his politically active father. Becoming father to an only son just days after the Great Depression closed the banks, Lawrence Sr. began calling the boy Pat to honor a close friend, Alexander “Pat” Paterson, who gave him a temporary loan to pay for the newborn’s birth — or so the story goes.

In any case, friends found it almost impossible to say no if a call for last-minute help came from their best friend, Pat Kramer, who knew all their nicknames and routinely called with advice, a joke and a question: “Are the kids all right?”

So when contract talks with a city garbage hauler stalled and curbside cans began piling up, the new mayor managed to persuade a contractor friend in Bergen County to give him the resources to move garbage somewhere safe while negotiations continued. The hiding place remained secret for decades.

“Hinchliffe Stadium,” he finally told me, “and you guys in the press never knew.”

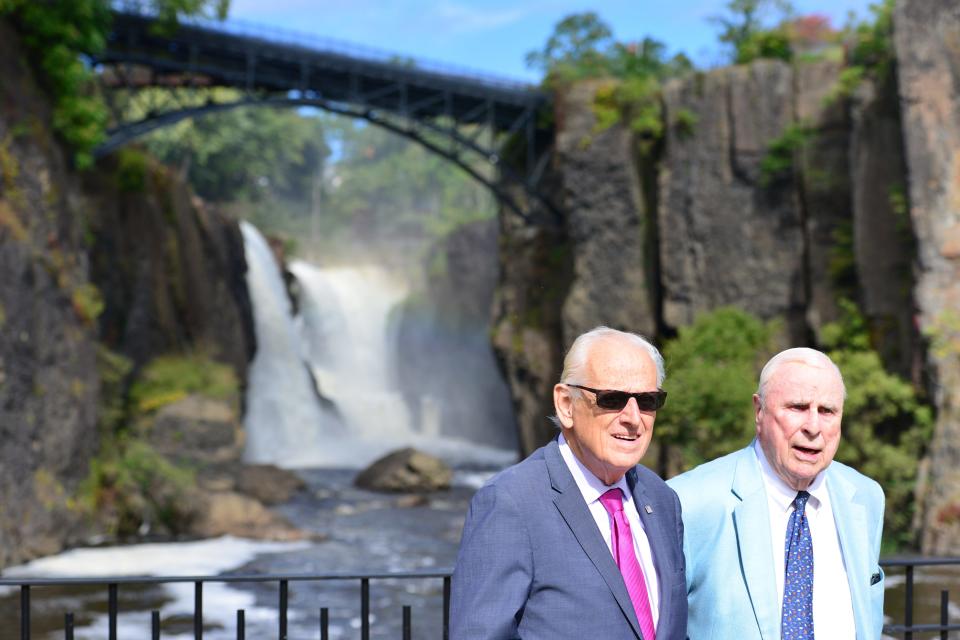

Great Falls visionary: Pat Kramer, Paterson mayor who helped create Great Falls park, dies at 90

'Divine intervention'

Persuasion wasn’t always enough, however. During a wearying midnight negotiation with civil rights leaders in 1968, Kramer thought he’d reached a settlement that would end a lengthy City Hall sit-in over the police use of the chemical spray Mace. But he misjudged.

“We were nearly out the door when one woman sat on the floor and screamed, ‘Where are the men?!’ over and over again.” he recalled. “She refused to leave, and neither would the men with her. It was late, so I went home.”

In an attempted sit-in years earlier, Graves ordered police to break up the demonstration — an action Kramer refused to take. So fate took a hand, or so it seemed.

At 3 a.m. on the sit-in’s eighth day, a blackout shut down City Hall. An electrician declared that the electrical failure was dangerous enough to require evacuation. The Fire Department agreed and cleared the building. Once they were outside, police barred demonstrators from returning.

Was the blackout a ruse to save face? Kramer always gave a stock answer:

“Divine intervention.”

“He had a great sense of humor — the best,” noted Pascrell. “But when it came to doing the work, he was deadly serious.”

First-person, first-hand account: While in the Newark riots, I saw 'the rawest sort of rage'

Ambition for Paterson reached the White House

That became clear in 1970 when Paterson was unexpectedly replaced by Newark on a list of 19 urban centers initially promised huge federal Planned Variations grants. The impact on the Silk City budget would be devastating. At a National Conference of Mayors forum in Washington, the mayor reminded President Richard Nixon that Paterson was one of the few Republican-run cities on the original list.

“I’ll have John Ehrlichman look into it,” Nixon responded, according to Kramer.

Appreciation continues below gallery.

Ehrlichman, who later was jailed for his part in the Watergate scandal, apparently did what Nixon yes-men normally did, because Paterson was added to the list.

By then, rubbing shoulders with a president and living in the shadow of the World Trade Center had taught Kramer to think well beyond the borders of his 8.3-square-mile hometown. After returning to City Hall in 1974 following a stint in Gov. William Cahill’s Cabinet, he wanted to make a big splash.

“We want Philippe Petit,” he told me.

A month earlier, the French aerialist had earned worldwide headlines by walking a tightrope between the Twin Towers. Kramer’s way to guarantee a huge turnout at the city’s Great Falls Festival was to hire the Frenchman to do the same over the Paterson waterfall. But the Chamber of Commerce couldn’t provide the $4,500 fee.

“Do you think your boss could reimburse the chamber?” he asked me.

I was working in radio at the time — for WPAT. The station manager agreed, but only if the donation wasn’t publicized until after Petit completed his walk.

“If he falls, we’ll look awful,” he explained.

The Frenchman’s flawless 30-degree ascent, executed in front of a huge sign proclaiming PATERSON, exposed the falls to an international audience far larger than the 30,000 festival attendees. For the mayor, its timing was nearly perfect — less than a month after Gerald Ford replaced Nixon in the Oval Office and less than two years before the nation’s 200th anniversary.

Kramer’s brain was spinning.

“If we can only get the president to come to Paterson,” he said.

The stars appeared finally to be lining up for genuine change. After all, Ford’s Treasury secretary, William Simon, was a Paterson native.

The mayor, his wife, Mary Ellen, and dozens of volunteers had been working for nearly a decade to get Washington bureaucrats to put the falls region on the map by designating it a National Historic Landmark. Among other factors, this formidable task meant they had to convince the Ford administration that a forgotten spot in North Jersey was the place where Hamilton began turning an agrarian society dependent on slavery into a manufacturing economy based on freedom.

They succeeded. A month before the bicentennial, Ford arrived with an order designating national status for the 35-acre falls site and $11 million in grants to improve the region.

“It changed everything for us in Washington,” recalled Kramer, “because officials knew this was something the president wanted, and the doubting Thomases began to say, hey, something good might really happen there.”

Something good did happen. A bridge overlooking the park was strengthened. A small park was improved. Old mills were spared demolition. Some were converted into moderate-income housing. Out-of-towners began visiting the site. The Rogers Locomotive and Machine Works was refurbished and turned into the Paterson Museum.

Great Falls Park — finally

Kramer’s jousts with presidents weren’t finished, however.

His final bout occurred after a flight to Central America. Kramer was there to bring back a Paterson-made locomotive that figured in the construction of the Panama Canal. Sensing trickery, Panamanian officials petitioned President Jimmy Carter to halt what they called the Great Train Robbery.

“All our paperwork was in order,” insisted the mayor, who later recalled coaxing canal workers to hurry the loading of old Engine 299 onto a canal boat before irate Panamanian officials arrived to reclaim it. “The guys who helped me couldn’t have been more cooperative,” he said much later on a trip to the Paterson Museum, where 299 is enshrined.

The quip was vintage Kramer diplomacy: portraying an international incident in a way that might least offend the other side.

At 48, he finished a distant second in the 1981 Republican gubernatorial primary to Thomas Kean, who narrowly won the November election. The mayor didn’t seek a fifth term, and Graves, then a state senator and a member of the Kramer administration, easily won election to succeed him. For his part, Kramer became the operating head of the same Allendale contracting firm that helped him elude a garbage crisis years earlier. After Graves’ death in 1990, Kramer failed in a bid to take his Senate seat.

But these disappointments didn’t seem to embitter him. In occasional lunches and Hudson River trips on his boat, the Remark, over the last three decades, he loved trading stories about the old days, and rarely, if ever, spoke ill of old opponents. Besides, he maintained a passion for the falls — his chief achievement — by remaining a member of the nonprofit Great Falls Development Corporation, where he continued to battle vigorously for the historic site to be turned into a National Park Service facility.

“The Park Service has the resources to do what Paterson never could,” he said.

That argument even won the support of his bitterest opponent: Councilman Thomas Rooney, a former mayor who narrowly lost the top job to Kramer in his successful 1974 comeback attempt. Consistent city government support helped get the measure through Congress and ultimately to the desk of President Barack Obama, who signed it into law in 2009.

A lasting legacy of service

Kramer is also known for adding minorities to his key staff, streamlining government by hiring out-of-state professionals to run it, and getting the state to build enough Route 80 exit and entrance ramps to ensure that Paterson “doesn’t remain a whistle-stop to nowhere.”

But rallying people to work for a lasting cause that benefits the entire region remains his chief legacy.

Today, the fence and slippery ledge where two young men once foolishly risked their bodies to view the roaring grandeur of an Ice Age wonder is now a well-groomed oasis inside a promising urban landscape. Besides taking in the scenery, visitors can see a tasteful bronze plaque honoring Mary Ellen Kramer, the gracious woman who died 30 years ago — much too soon to see her dream realized.

If the plaque and the history pamphlets at the nearby visitors center can’t answer people's questions, park rangers are there to help. Baseball fans are directed to adjacent Hinchliffe Stadium, where a once-abandoned ballpark is now a modern, $104 million minor league playing field that features a museum focusing on the old Negro baseball leagues that played there in the 1930s and '40s.

Kramer’s successors aren’t finished, though. Some want additional amenities there. Maybe an amusement park with cable cars. Maybe not. It’s hard to see the next big deal. As an old friend once told me, magnificence isn’t usually visible from the parking lot. It takes nerve to look closer.

John Cichowski, The Record’s retired Road Warrior columnist, is a Paterson native. He can be reached at jwcichowski@optonline.net.

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Paterson NJ: Pat Kramer's vision for his city and the Great Falls