PATH is down half its riders. Why its leader is moving ahead with $1B expansion anyway

JERSEY CITY — Shortly after Clarelle DeGraffe was named general manager of the PATH transit system in 2019, she was riding the train during morning rush hour when it came to a stop outside Grove Street Station.

The man next to her in the crowded car turned and said, “I’m so sick of this train. These people do this all the time,” DeGraffe recalled on a recent day in her corner office at 1 PATH Plaza in Journal Square.

DeGraffe told the man who she was and said the sudden stop was due to a glitch in the train's new signal system that they were trying to work out. She then gave him her number, saying, “Shoot me a text and let me know what your experience is if you’re having an issue on the train.”

DeGraffe learned two valuable lessons: Always put the customer experience first, but don't give out your number to strangers.

“He started to get out of line,” she said, but “I think it made him think a little bit more about the challenges that we have."

Throughout her 33-year career with the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, DeGraffe moved her way up from construction inspector to overseeing some of the largest jobs in the tri-state area, including the construction of Newark Airport's AirTrain and several projects during the rebuilding of the World Trade Center.

She is now the person charged with navigating PATH through two seemingly conflicting problems: luring back half of its customers lost to new work-from-home patterns while leading a billion-dollar plan that will expand capacity and upgrade the 114-year-old transit system to prepare for expected development booms in the future.

"We’ve got to do that maintenance and while we have the lower volume, so it’s a balance of really trying to provide service for the volume of people and maintaining the system, which is key, or else you’re not going to have a system," DeGraffe said.

$1 billion and 50% of ridership

Across from DeGraffe’s desk is a large, framed, black-and-white sketch that exposes PATH’s hidden tunnels and tracks that snake underground throughout Hudson County.

When DeGraffe looks at the picture, she sees an impressive and complex system of tracks engineered in the 1800s that still manages to carry thousands of people under the river each day.

“When you’re riding uptown, this is what you’re going through," DeGraffe said, pausing to point to the frame. “I love that picture, because to me it shows such ingenuity and just forethought that’s just amazing."

But like most transit systems, PATH is merely a means to an end for commuters who want to get where they are going on time.

It's why DeGraffe is forging ahead with a $1 billion plan designed to address the root causes of delays. It includes upgrading the signal system, buying more train cars and expanding train sets and platforms to fit another one or two cars, depending on the line. Studies are also underway to examine expanding stations in the Marion neighborhood of Jersey City and at Newark Liberty International Airport.

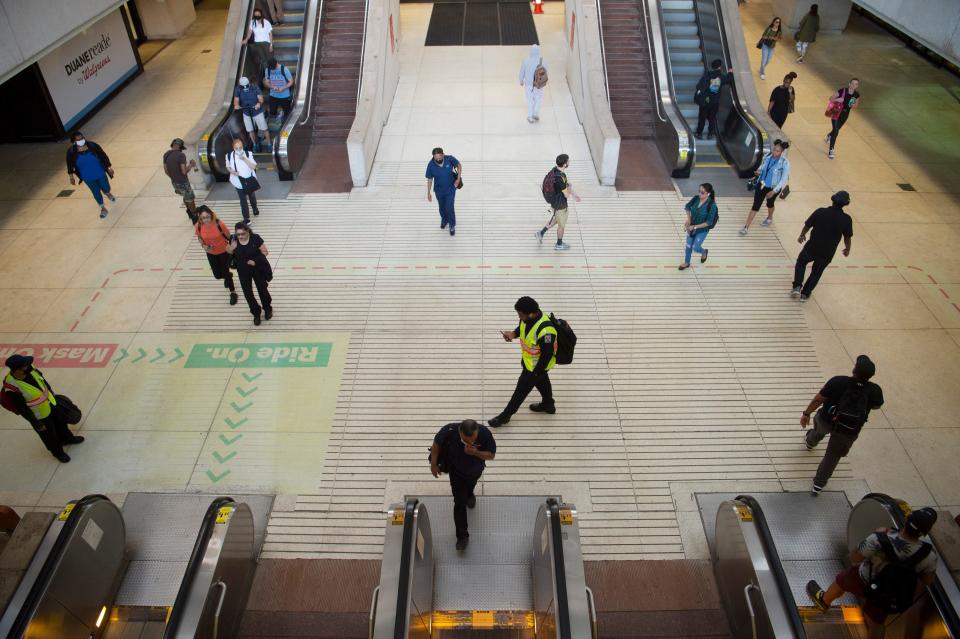

PATH’s ridership was growing at a rapid clip before the pandemic. Every morning rush-hour train had an endless flow of passengers packed in, "sardine-like," as DeGraffe put it. More than 284,000 people used the system each weekday in 2019, and that number had been increasing on average more than 2% each year since 2012 as development boomed in Hoboken, Jersey City and Harrison.

On just 14 miles of track, PATH carries nearly as many riders as NJ Transit does on 467 miles of track.

As of May, about 50% of riders have returned to PATH compared with pre-pandemic figures, a rate similar to transit peers like the New York subway system (62% return) and NJ Transit’s commuter rail, which was at 50% last month.

At its height in 1927, PATH — known in the 20th century as the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad — carried more than 113 million passengers from Newark and Hoboken across the river to lower Manhattan and eventually up to 33rd Street.

But since being acquired by the Port Authority in 1962, PATH has at times been a punching bag at the bi-state agency, as it requires subsidies from other profit-generating departments. One transit expert, quoted in a news article in 2015 when the Port Authority considered making cuts to PATH's overnight service to save money, said the transit system was something agency leaders have spent years "whining" about.

Port Authority Executive Director Rick Cotton said that attitude has changed.

As some Port Authority projects were deferred due to pandemic budget strains, PATH's billion-dollar improvement plan stayed intact. A big reason for that was DeGraffe, Cotton said.

She and her team, he said, “came up with really a very impressive plan to be able to move to nine-car trains … it’s an example of problem-solving and taking on a challenge and embracing what [for] most railroad systems are extraordinarily difficult challenges."

More: NJ Transit handed out $265,000 in raises last year. Nearly all of it went to eight people

NJ news: Murphy's property tax plan would give some residents up to $1,500. Find out what you'd get

Despite a slow ridership return, DeGraffe said, the need for improvements to increase capacity is still there. The reasons for it simply changed.

“We had promised adding capacity because of the sardine-like nature of our trains, but that was no longer the issue. What became the need now was the spacing on the cars,” DeGraffe said. “It’s really about being close to people that I don’t know, and that’s the justification to expand.”

Health and safety are the top concerns for customers returning to public transportation, according to research by the Regional Plan Association.

“Better service, lower fares and then measures to ensure … health or personal safety are the items that polling respondents in the region said will bring them back onto transit,” said Zoe Baldwin, New Jersey director of the nonprofit advocacy group.

'Whatever she says, you do’

DeGraffe was born in Haiti and moved at a young age to the East Flatbush neighborhood of Brooklyn, where her mother raised DeGraffe and her older sister.

“[She] taught us we can be whoever we want, we can do whatever we felt we could do, but we needed to believe in ourselves, we needed to believe in God,” DeGraffe said.

Before pursuing engineering, DeGraffe figured out what she didn’t want to do.

Sitting in an architecture class at Brooklyn Tech High School, and later in a geotechnical class at Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, DeGraffe realized she liked the technical aspects, but couldn’t draw.

“I didn’t want to be locked away in a room and just designing for the rest of my life. I knew that wasn’t me,” she said. “I loved to be able to make decisions.”

Story continues below gallery

After graduating from Stevens with a civil engineering degree, DeGraffe embarked on what would become a decades-long career at the Port Authority, starting as a construction inspector at age 22 at JFK Airport in 1984.

This is when DeGraffe said she started to find her “voice” — what one colleague described as a “quiet assertiveness," a calm, empathetic but serious tenor that expresses her confidence and empowers her decisions.

DeGraffe credits a crew of 12 other inspectors at JFK — all men — with helping her.

“They would say, ‘Whatever she says, you do,’ ” DeGraffe said. “I knew I had these guys who had my back, so the contractor knew that even though I was wet behind the ears, I was green, that somebody else was coming behind me and they had to do whatever the drawings said, whatever I told them to do.”

John Bolger, who retired from the Port Authority in 1995 after 34 years, met DeGraffe toward the end of his career and just as she was getting started, in her early days at JFK.

“The office was really comprised of all men," said Bolger, who said they all looked out for DeGraffe. "She was just great. She carried out every assignment to a T."

But managing projects in a male-dominated field wasn’t always easy.

DeGraffe recalled one time when a contractor came to her with a problem and she responded with how she wanted it fixed. Dissatisfied, the contractor went to a male colleague of DeGraffe’s, explaining the same problem, and the colleague responded with the same solution as DeGraffe, which satisfied the contractor.

“I was like, you know what, I can either get after him and say, ‘You didn’t listen,’ but you know what — he did what I wanted anyway,” DeGraffe said.

After taking five years off to care for her newborn son, DeGraffe returned to the agency in 2007 to help rebuild the World Trade Center. She oversaw the construction of the underground pedestrian corridor from the World Trade Center to the Brookfield Place mall, a job that took place while an active roadway was above the construction zone. DeGraffe, who lost 13 colleagues when the Twin Towers were attacked, also created and directed the security center that vetted vehicles before they came on site.

“There was no such thing as missing a deadline, because the whole world was watching you,” DeGraffe said. “Either you delivered, or you got out.”

“Every day she would show she’s up to the task and could handle it, and I would back away and say, ‘You need me?’ and she said, ‘I’m good,’ ” said Steve Plate, who oversaw the World Trade Center construction and was DeGraffe's manager. “It’s a rare skill that you develop over time: When things get rough, she gets calm and quiet and thoughtful and very in control.”

Raishea Haines, assistant superintendent at PATH, where she has worked for 17 years, first met DeGraffe when her team gathered to do a “shadow operation,” or a run-through of shuttle service being provided during construction at World Trade. Haines said DeGraffe “commanded the room" at the meeting, but left a lasting impression afterward when Haines was walking the revised corridor commuters would take during the tunnel shutdown.

“And I looked beside me and Clarelle was right next to me, of course ... ‘This as the deputy director, walking right here with me.’ And that's how she's been since she entered PATH,” Haines said. “I have seen executives that were out there. … Clarelle is out there, but she's out there serving a purpose.”

John Burkhard, who oversees the superintendents, said many PATH executive directors in his 25 years with the agency didn’t interact much with ranks below upper management. But that’s not DeGraffe’s style.

“It’s the open door, and it extends down through me,” Burkhard said. “It’s always, ‘What can we do better? How can we prevent this from happening again?’ drilling down to root causes.”

An example of that came last October when customers began tweeting about increasing numbers of riders during overnight service. Haines decided to come in with the midnight shift to see what was going on, and DeGraffe showed up, too.

“Rather than just look at cameras, we wanted to do first-hand, so I said, ‘I’m coming,' ” DeGraffe said. “And what happened was, as coronavirus was going down, some clubs were opening up on Sixth Avenue around Ninth Street, and people were just enjoying themselves and then they were coming home at 1 in the morning, midnight.”

After that, DeGraffe said, the agency added more trains on Friday nights.

“We have what we need in Clarelle. I think the empathetic side that she brought and the way she’s able to solve problems is what we needed,” Haines said. “With regard to the pandemic, I think it’s a matter of time. We’re going to get where we have to go, it’s factors that are out of our control, but we have what we need in place.”

Colleen Wilson covers the Port Authority and NJ Transit for NorthJersey.com. For unlimited access to her work covering the region’s transportation systems and how they affect your commute, please subscribe or activate your digital account today.

Email: cwilson2@gannettnj.com

Twitter: @colleenallreds

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Why PATH is expanding after losing riders post-COVID