Patinkin: I've seen the faces of Gazan Palestinians. They haven't been forgotten

From what I can tell, Gaza has not changed much since I was there 30-plus years ago.

Certainly not visually.

As I neared the border by car back then, the Israeli landscape was vibrant with planted melons and citrus. The moment I got inside Gaza, past the checkpoint, everything turned to black and white.

From the pictures I see today, it’s the same.

And so, it seems, is the circumstance.

Since the horrific Hamas attacks of Oct. 7, I have written columns supporting Israel. A number of readers have asked why I don’t also write of the other side.

I don’t see two sides to Hamas.

But in 1991, I saw the human faces of Gazan Palestinians.

Today, I am remembering them.

I’d hired a local driver named Ismail, a young, thin, upbeat guy who’d studied in America and was thrilled to have paid work in a place where jobs were scarce.

Soon we arrived at a refugee camp in the southern city of Rafah, where there seemed to be as many donkey carts as cars, the roads covered with sand.

You hear “refugee camp” and you picture fenced-in tents and huts. It was more like a slum city, no boundaries.

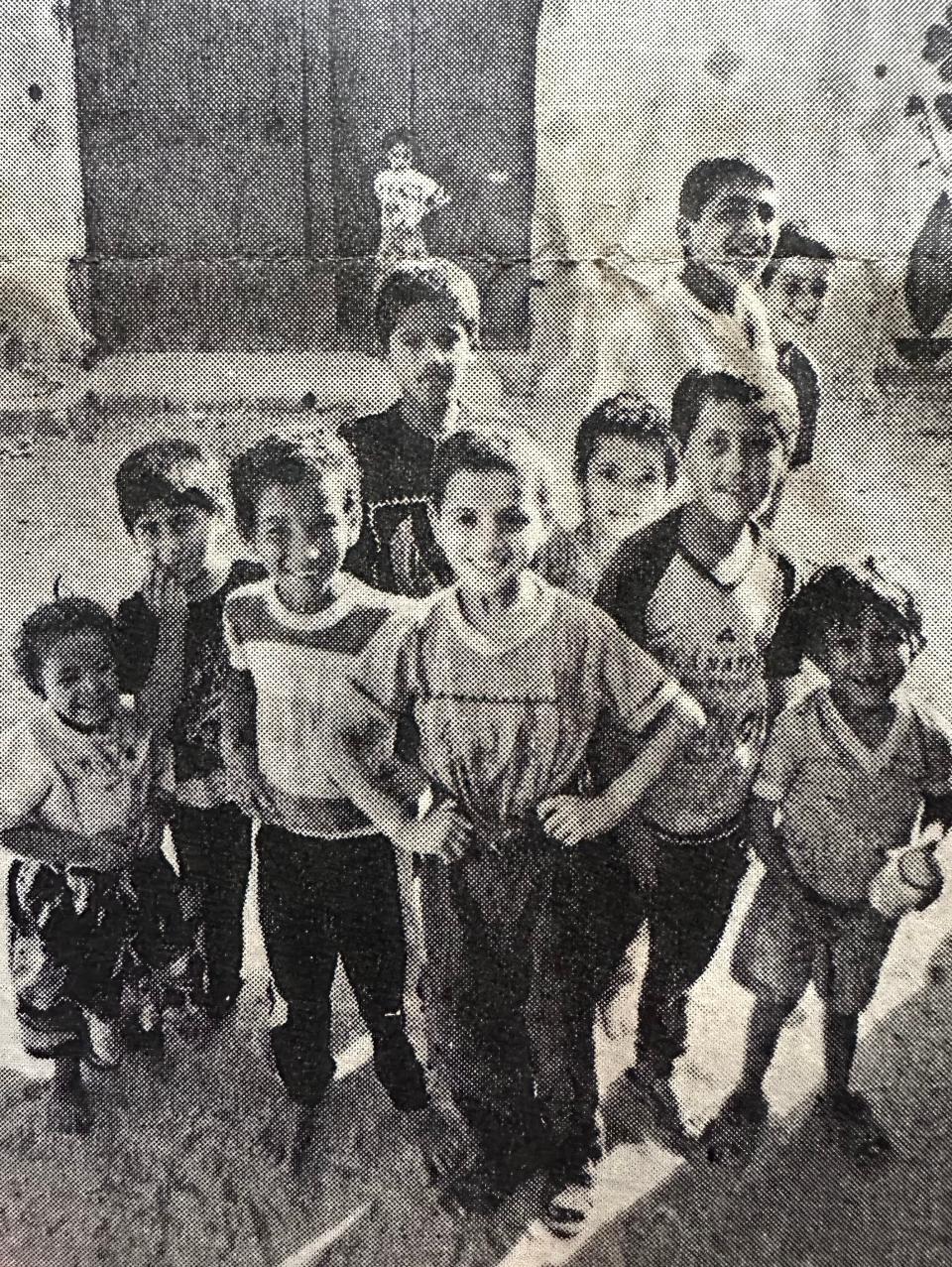

Kids were everywhere, and it’s still like that today, Gaza’s population of 2 million being among the world’s youngest, with almost half under 18. We stopped to talk to a dozen such kids, from perhaps age 5 to mid-teens. They gathered around us, laughing and intrigued.

I asked Ra’eed, who was 14, where he lived. His answer tells you one reason the conflict continues. It would likely be the same answer among the Ra’eeds of today in Gaza.

“Beersheba,” he said.

But that's in Israel, I told him.

“My father was born there,” he said. “It's my home.”

But you've lived in Gaza your whole life – isn't this your home?

“Beersheba,” he repeated.

I asked him what Beersheba is like.

Beautiful, he said – green trees and orange groves.

When did he last see it?

“I’ve never been there.”

Gaza is only 6 by 25 miles, so it didn’t take long to drive the length of it, to the Jabalia refugee camp in Gaza City. Once, Ismail said, things there were more lively, but the newly emerged Hamas had banned anything festive. That’s because of the Intifada – the often violent protests at the Israeli army, which at the time controlled Gaza.

"We used to have parties,” said Ismail, “bands when people got married. Now, you can't have music at weddings."

Public concerts in Gaza, especially of more modern genres, are still discouraged or banned by Hamas today.

The mentality, Ismail said, is to keep the focus on the struggle – on a Palestinian state.

As we walked down narrow streets, with scrawny cats scampering out of trash piles, groups of young men eyed us. I asked Ismail if it was safe.

Oh yes, he said – outside the struggle, the Palestinian character is civil, with hospitality to visitors.

We headed past a gate and met Mohammed Musselem, a hefty, 60-ish man in shorts and an old T-shirt. He was living in a tent next to his in-laws. The Israelis, Musselem explained, bulldozed his home after his son was accused of throwing a bomb at the army.

He told me he was born in Israel but fled during the nation’s founding war of 1948, and he has been here since.

His family gathered around us, honored by my visit, bringing sweet Arabic tea with rosemary. Another of Musselem’s sons, Rafiq, 23, joined us.

I told Rafiq I'd heard Israel offered new housing to folks here in Jabalia, but they rejected it. Was that propaganda?

"We don't want their houses," Rafiq said. "We won't leave this camp until we get our state. We must keep this camp to remind the world to solve our problem."

One looks back today and wonders how different things might have been had such development been embraced, instead of Hamas channeling resources to rockets.

Musselem said he used to have Jewish neighbors, and they got along.

So Arabs and Jews can live together?

"We did before. We can again." But first, he said, the Palestinians must have their own homeland.

I spent the night at Marna House, a gracious old inn with a shaded veranda – one of the few hotels in the territory. Our breakfast server was a boy named Mounzir, perhaps 16, who seemed thrilled to wait on us. Later, I mentioned to Alya Shawa, the proprietress, how accommodating the boy was.

"It is the Palestinian culture," she told me. "Even if a family is poor, they will give all they have to a guest. We are happy if they are happy."

I checked the guestbook and was impressed at names and titles, many of them diplomats from Arab countries.

"All the delegates come here," Alya explained.

Many, she said, came promising aid.

So the Arab nations are committed to your cause?

Her answer stunned me.

"They're all rubbish," Alya said. "They think if they come here and spread a little money, the problems would be done. But we do not need that. The people can survive on bread. What they want is their freedom."

I picked up between the lines that folks like her also wanted freedom from local extremist leaders, but you didn't dare say that in Gaza.

More Patinkin: His niece murdered, her son shielded beneath her body: A family's final moments in Israel

She added: "Palestinians have no friends."

But to me, what a welcoming, gracious lady she was.

A few hours later, I went into the field with an American woman named Heather Grady, head of the local Save the Children office. She pointed out the TV antennas on homes, saying the poverty here, although profound, is not as bad as in some undeveloped countries.

But Gazans, she added, were still destitute. Beneath those antennas, in these small three-room houses, there were often 10 people.

When I asked what folks here are like, she said she’s known few people who dote so much on their children.

But she added that many kids grow up into politics alarmingly young.

Indeed, even 10-year-olds I talked to, and younger, proudly said they throw stones at Israeli patrol jeeps.

Finally, before I headed back into Israel, I stopped in a school courtyard to visit a group called the Bureij Sports Program.

More Patinkin: His parents survived the Holocaust, now this RIer watches as a friend is attacked in Israel

Abdul Moti, 31, one of the folks who ran it, told me his goal was to give kids a normal childhood – let them ride bikes, eat ice cream, play soccer. He tried to teach that all children are the same – Palestinians, Americans, Israelis. He wanted them to learn that, instead of hatred.

Indeed, these kids seemed to reflect the lesson. I sat with a half dozen, ages 10 to 13, and asked what they liked most about the program.

"Soccer," said Eyad.

"Just playing," said Hassan.

Why, I ask, do you come here?

"The streets are trouble," said Ali.

And what do you want to be?

A doctor, a teacher, a counselor.

Finally, I asked what their dreams were.

“Having my own homeland," said one, and the others said that’s their dream, too.

Then they went back to playing.

Yet before I left, another counselor told me this:

"We want them to be carefree. It's not possible here. They are in refugee camps, and their uncles are getting arrested, and it's not possible."

Perhaps most impossible was the mantra not just of wanting a homeland, but ancestral land throughout Israel. That was more the focus than building a vibrant Gaza.

And now it’s 30-plus years later.

Israel has since pulled out, and Hamas has risen.

At the time I was there, I’m not sure what I thought might happen decades hence.

Clearly, today, it’s no better, and things these past weeks have been a catastrophe.

I blame Hamas for that.

But for those who’ve been to Gaza, and met regular folks there, the heart breaks.

mpatinki@providencejournal.com

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: As war rages in Gaza, remembering the people met there 30 years ago