Patricia Hinton Sims, a Rock Hill civil rights crusader from the 1960s, dies at 79

Although male civil rights protesters in Rock Hill in the early 1960s went to jail for their beliefs in equality for Black people, often there also were female marchers who led the charge to change South Carolina and America.

Patricia Hinton Sims was one of those marchers while still a teenager.

Sims died Friday at age 79, according to officials at Robinson Funeral Home and an obituary in The Herald.

The young ladies who marched in Rock Hill in the 1960s were dubbed the “City Girls” because they were locals who risked violence, hatred and scorn to make their hometown, and the world, a better place.

The city of Rock Hill much later memorialized the City Girls at the Freedom Walkway in downtown.

Robinson Funeral Home owner Monique Ramseur, whose mother also was a City Girls marcher and civil rights activist in the 1960s and a lifelong friend of Sims, said Sims was “a beautiful lady inside and out.”

In her obituary, Sims was praised as a vital civil rights woman.

“Patricia was also a lifelong civil rights champion,” the obituary reads. “As a member of the well-lauded Rock Hill “City Girls”, she was a soldier for equality. Her brave actions contributed to moving Rock Hill’s civil rights movement forward through peaceful protests during the 1960’s.”

Sims’ enduring courage -- and the grace to forgive those who wanted integration between whites and African-Americans -- will always survive.

Rock Hill protests 1960, 1961

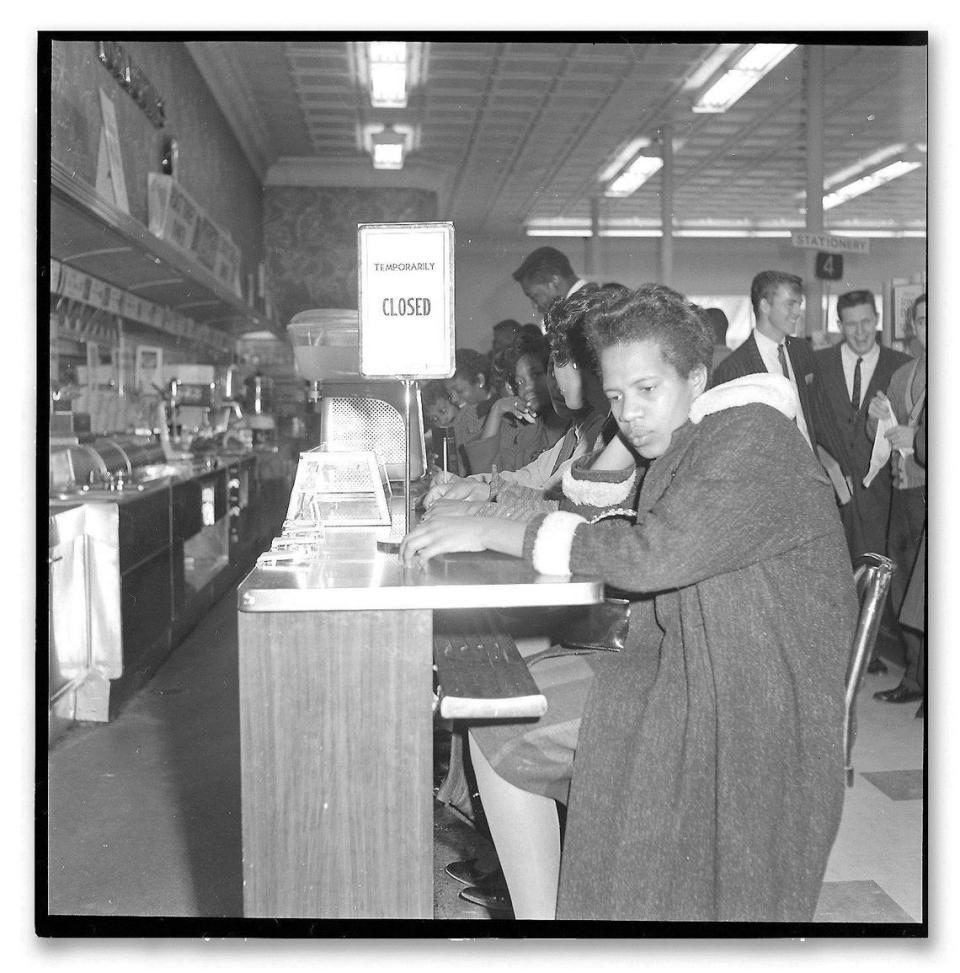

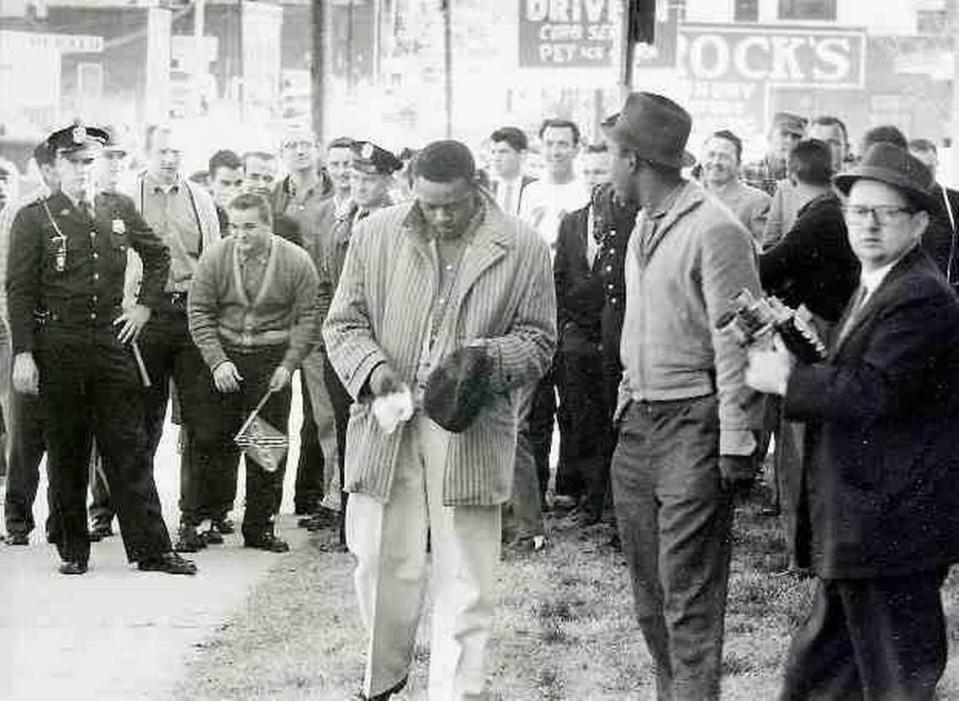

In 1960 and 1961, Black marchers often were on Rock Hill’s Main Street sidewalks and at sit-ins, protesting segregated restaurants and stores.

Sims and many other young Black women in Rock Hill, some of whom attended Friendship Junior College, marched with young men for more than a year starting in February 1960. They endured taunts, and threats.

Some of the men later would become the Friendship Nine. Those men chose jail instead of bail after their arrest, and conviction for sitting at an all-white lunch counter in January 1961. The men spent a month in the York County prison after they were convicted of trespassing.

The ladies did not sit at the lunch counter that day in 1961 because protest organizers who knew the young men would be jailed had safety concerns about how the females might be treated in the county prison.

The publicity from the “Jail, No Bail” movement pushed civil rights protests throughout America that eventually led to desegregation.

Sims later went on to finish college at Benedict in Columbia and was a teacher in Rock Hill for decades.

2009 forgiveness

In 2009, a man who was a former member of the Ku Klux Klan and admitted former racist made a public apology to some of the protesters he had threatened in the 1960s. Elwin Wilson, who died years later in 2013, said in 2009 that he was ashamed of his actions in a meeting with Sims and other protesters.

He wanted to apologize after reading in The Herald in January 2009 about Sims and other female protesters the day after Barack Obama was inaugurated president.

Sims and several other ladies and men from the protest movement, accepted Wilson’s apology in that historic meeting in 2009 held at the same lunch counter where the protests took place.

Sims and friends she had known all her life accepted the apology from Wilson and another Rock Hill man who admitted 1960s prejudice, and said how the act was a step toward healing wounds that had lasted for decades.

Wilson’s apology, and the grace of the people who accepted it, was covered in The Herald in 2009. The meeting later became international news when Wilson admitted to beating protester John Lewis later in 1961.

Wilson apologized, and Lewis, by then a U.S. Congressman from Georgia, accepted the apology that was later in 2009 broadcast all over the world. Lewis died in 2020.

Funeral information

A homegoing celebration for Phyllis Hinton Sims will be 11 a.m. Friday at Trinity Baptist Church in Rock Hill.

Burial will follow at Grandview Memorial Park on Cherry Road.