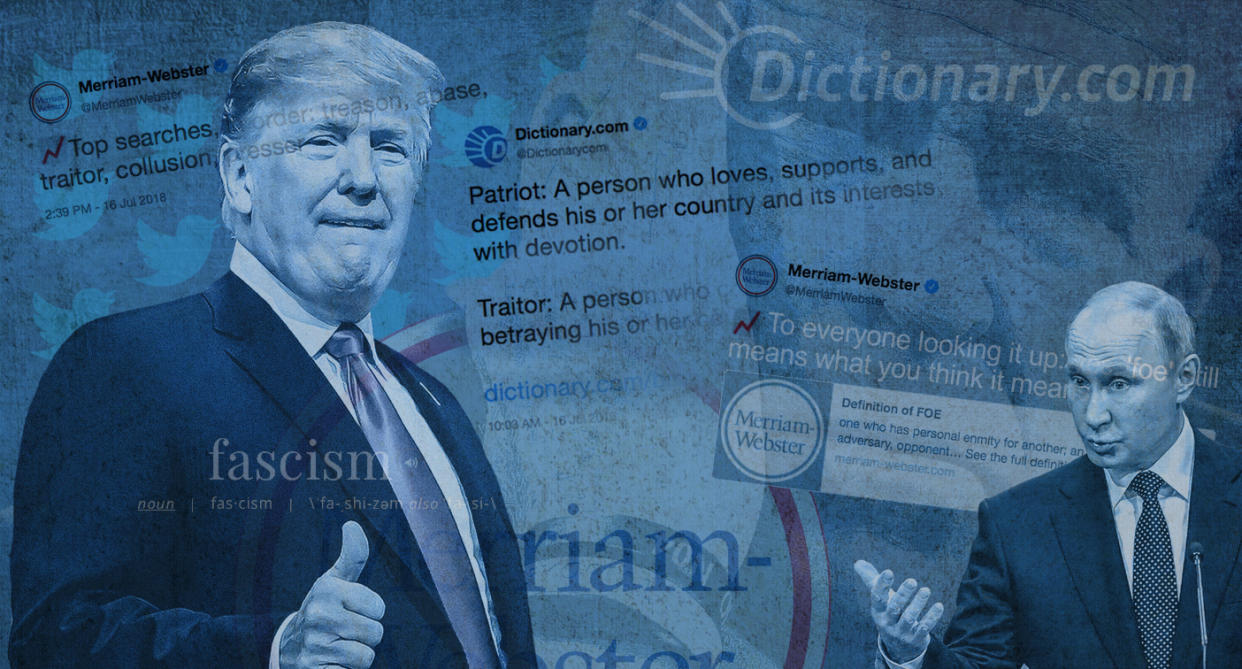

'Patriot' vs. 'traitor,' 'yes' vs. 'no': Are dictionary sites trolling Trump?

In case you were wondering, the definition of a patriot is “a person who loves, supports, and defends his or her country and its interests with devotion,” and a traitor is “a person who commits treason by betraying his or her country.” That is courtesy of Dictionary.com, which tweeted those definitions on the morning of July 16 — shortly after President Trump’s press conference with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Helsinki, and a day before former CIA Director John Brennan described Trump’s behavior as “nothing short of treasonous.”

On July 18, a day after Trump corrected his answer to a question about whether he believed Putin’s denials that Russia meddled in the 2016 election — saying he’d been tripped up by a double negative — Merriam-Webster helpfully provided its followers with the definitions of “yes” and “no.”

‘Yes’: an affirmative reply

‘No’: a negative answer

— Merriam-Webster (@MerriamWebster) July 18, 2018

The two dictionary sites have been shaking up the traditionally sedate world of lexicography at least since the 2016 election, leading to stories with headlines such as “Dictionary.com is back to dissing Donald Trump and Twitter can’t handle it” and “Sassy Merriam-Webster trolls Trump on ‘Foe.’” Dictionary.com received 43,000 likes for its Helsinki-themed tweet, and Merriam-Webster got 51,000 for its tweet. Both companies boast larger Twitter followings than other dictionary sites that have less topical social media presences.

But neither company owns up to a political agenda. Lauren Sliter, senior manager for marketing and content strategy at Dictionary.com, told Yahoo News that the company’s intention is simply to highlight words that begin to trend among users. “Misogyny” has trended multiple times, and “xenophobia” was its word of the year in 2016.

Just before the presidential election, Merriam-Webster changed its Twitter header to the word “Gӧtterdämmerung,” a German word that means “a collapse (as of a society or regime) marked by catastrophic violence and disorder.” It designated “surreal” as its word of the year in 2016, based on its trend-watch tool, which identified that as the single most searched word on the site that year. Recently, the word “emolument” trended after a federal judge allowed a case concerning Trump’s business ties to move forward.

We’ve updated our Twitter header in honor of the election. pic.twitter.com/mOFT8sUlVD

— Merriam-Webster (@MerriamWebster) November 7, 2016

“While it’s true that speed and tone of Twitter sometimes makes it easy to consider these posts to be ‘corrections,’ we are merely reporting that some statement or event sent the public to the dictionary,” Lisa Schneider, chief digital officer and publisher at Merriam-Webster, said in an email to Yahoo News.

The companies disputed accusations that they are trolling the president — or anyone else — with their decisions of what definitions to highlight.

“By definition, to troll someone, you have to have the intent of upsetting them,” Sliter said. “That’s part of the written definition of trolling, and that’s definitely not our intent. We are not posting content to make people feel upset or threatened or shamed.”

Kory Stamper, a former lexicographer for Merriam-Webster and an author, said politicizing posts — even ones that provide the definition of words the president uses or misuses — are inevitable in today’s climate. She said some posts could be defined as trolling, but generally, that’s not the mission of dictionaries. She believes public interest is driving the Twitter posts.

“I think we’re in a place, politically, where people are paying a lot more attention to words than they used to, and we’re so polarized,” she said. “Everything is political — and whether that’s a good or a bad thing, that’s just the reality.”

The Merriam-Webster trending words, and subsequent Twitter posts, are a reflection of the times, Schneider said. “We don’t choose the words that people look up.” Asked if users were actually searching for the meanings of the words “yes” and “no,” Schneider replied: “Most of the focus is on trending words, but one can certainly find a few tweets on language use in the public eye that wasn’t necessarily a trending lookup, but was a topic of conversation. When people are talking about meaning, and often calling on us to comment, we do step up to fulfill our mission of clarifying meaning. It’s also true that when a public figure uses language in a remarkable way, it’s fair game for us to comment on the language use without that being political.”

Stamper said that dictionaries are not influencers of culture. Rather, they respond to what’s happening in the world of words. And now, with social media, they have the chance to do so more swiftly than ever before.

“Every word we choose to use tells the people listening to us something about us,” Sliter said. “The words we choose to use are shaped by who we are. So I think we have this responsibility of holding people accountable by saying, ‘You know what? The word you used has a very specific meaning; it’s written right here. We can point to that as fact.’”

Although the companies are grabbing the public’s attention, dictionaries and controversy is not a new concept. The invention of the American dictionary was a political statement itself. Noah Webster wanted to separate Americans from the English, so he created his own dictionary and took the letter “u” out of words such as “colour” and “favour.”

Rosemarie Ostler, a linguist and author, told Yahoo News that Webster added political words to his dictionary, and in that way shaped how Americans would view themselves.

“In some ways, dictionaries are always a little bit political because they are dealing with culture,” Ostler said. “I don’t think what’s happening on Twitter is exactly the same thing, but to some extent, maybe it is because a lot of what you’re seeing is people following the culture.”

There was furor in the 1960s over the addition of “ain’t,” and in 2011, the addition of “bromance” caused some to lament the death of the English language.

But, Stamper said, lexicographers now have a different view of their role, which is to accurately define what words mean. The assumption that dictionaries are a form of commentary on politics and culture is a misapprehension.

“The idea that the dictionary is a record rather than a bellwether or a trendsetter — that’s something that’s just not commonly known,” she said. “The culture has gone somewhere, the language is catching up and the dictionary is a mile behind it — trying to keep up, running with asthma inhalers.”

Correction: An earlier version said Merriam-Webster’s word of the year was “fascism.” That has been corrected to “surreal.”

Read more from Yahoo News:

Former Trump official: No one ‘minding the store’ at White House on cyberthreats

Voting rights advocates wary of Kavanaugh’s nomination to Supreme Court

No experience necessary? Trump and the future of the celebrity candidate

Progressive Dems try to catch some of Ocasio-Cortez’s lightning in a bottle

Photos: Violence, poverty and politics: Why Hondurans are escaping to the U.S.