Paul F. deLespinasse: Today's problems aggravated by political apathy

Most people aren't interested in politics. Political scientists have trouble understanding this. We wonder why everybody doesn't share our enthusiasm. But widespread apathy is a fact, and we need to understand how it magnifies the influence of fanatics and aggravates political polarization.

Political apathy grows out of the fact that most people are mainly concerned with immediate matters — getting an education, earning a living, getting along with family and friends, enjoying life.

Time devoted to thinking about politics produces little immediate benefit. Individuals only have one vote out of thousands or millions. The same amount of thinking about personal decisions may make a much bigger difference in our lives.

These personal decisions could include what profession to enter, how long to continue formal education, whether to get married and to whom, whether to have children, where to live.

Little wonder, then, that many people don't pay attention to politics until election time nears, if then. No wonder that most people don't vote in political primaries, which come months before the elections in which officials are finally chosen. No wonder many people don't ever bother to vote.

Getting information, including political information, costs us — scarce time, at the very least. The "principle of rational ignorance" tells us that when the value we place on additional information is less than its cost, it is rational to stop seeking it.

Political apathy is nothing new. In a 1945 Gallup Poll, 5% of Americans could not identify Harry Truman, then president of the U.S.! More people were able to identify boxer Joe Lewis (94%) and comedian Bob Hope (88%) than could identify Thomas Dewey, who had been defeated in the previous year's presidential election.

The new secretary of state was identified by fewer people (51%) than could identify Charlie McCarthy (a puppet), Frank Sinatra, and comic strip character Dick Tracy!

The political apathy of the majority creates situations where small minorities of people who are extremely interested in politics can cause a lot of trouble. The one thing extremists of all persuasions — left and right — agree on is that politics is of ultimate significance and that if the political order is bad or fails in some respect all is lost.

Mao Tse-tung, the Chinese revolutionary leader, for example, opined that: "Not having a correct political outlook is like having no soul." The totalitarian philosopher Herbert Marcuse charged that the American political system "isolates the individual from the one dimension where he could 'find himself'; from his political existence, which is at the core of his entire existence."

The high level of political polarization in today's United States is probably because the candidates of the two main parties are chosen in separate primary elections.

In primary elections, those fanatically interested in politics turn out enthusiastically but the majority — being politically apathetic — don't vote until the general election, if then. Right-wing enthusiasts dominate Republican primaries, and left-wing enthusiasts dominate Democratic primaries.

Republican legislators therefore fear making reasonable compromises with Democrats because they might get "primaried" and lose the next primary to a more dogmatic conservative. Conversely, Democratic legislators hesitate to make reasonable compromises with Republicans, fearing loss of the next primary to a more fanatical liberal.

General elections therefore force the apathetic but moderate majority to chose between extreme candidates both of whom they find distasteful. This hardly increases their enthusiasm for paying more attention to politics!

A possible "fix" for this problem is to have a single primary in which all parties and independents participate, sending the top three or four winners to ranked choice general elections, much as in today's Alaska. Voting in the same primary, left and right wing fanatics would at least cancel each other out.

It would be even nicer if larger numbers of Americans would also take a moderate interest in political participation, depriving the extremists of their present influence.

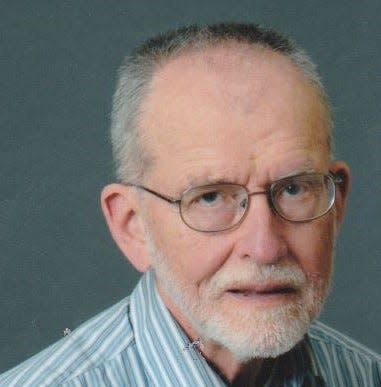

Paul F. deLespinasse is a retired professor of political science and computer science at Adrian College. He can be reached at pdeles@proaxis.com.

This article originally appeared on The Daily Telegram: Paul deLespinasse: Today's problems aggravated by political apathy