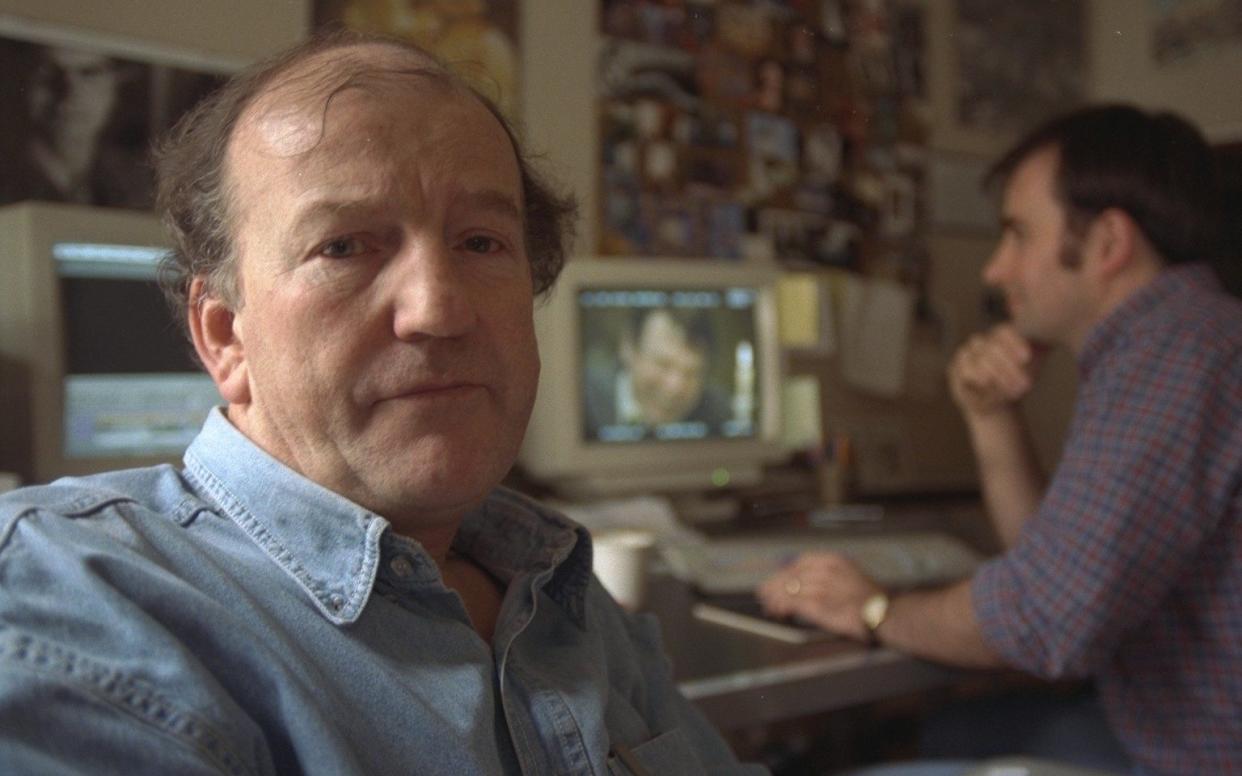

Paul Watson, fly-on-the-wall documentary-maker known as ‘the godfather of reality TV’ – obituary

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Paul Watson, who has died aged 81, was a pioneer of the “fly-on-the-wall” documentary and credited, to his disgust, though not unfairly, with being the godfather of today’s reality-TV genre.

Watson was best known for his controversial BBC series The Family (1974), which followed the fortunes of the “ordinary working-class” Wilkins family of Reading, and Sylvania Waters (1993), a similar venture following the Donahers – a nouveau-riche family in Sydney, Australia. He was also known for persuading Britain’s upper-middle classes to behave badly on camera in The Fishing Party (1985) and The Dinner Party (1997).

The raw-looking style of fly-on-the-wall filmmaking suggests that no contrivance or hidden agenda is involved, but of course no situation in which a film crew and director are present can ever be regarded as merely observational.

Watson’s track record boasted thoughtful work such as The Factory (Channel 4, 1995), a series about management-shopfloor relations in a struggling Liverpool manufacturing firm, and Malcolm and Barbara: A Love Story (ITV, 1999), an intensely moving and critically acclaimed portrait of a couple whose lives were turned upside when the husband developed Alzheimer’s.

But in his fly-on-the-wall work he was accused by some of seeking sensationalism or peddling a political message behind a mask of objectivity. Many of those who featured in Watson’s films found that life after their brush with celebrity could never be the same again.

The Wilkins family, bus driver Terry, his wife Margaret and children, Marion, 19, Gary, 18, Heather, 15, and Christopher, 9, had been selected after Margaret answered an advert in the local paper. They were billed by Watson as “the kind of people who never got on television”. They were also the stuff of a TV entertainment executive’s dreams.

As Margaret informed the producers, Marian was living in sin under the family roof with the lodger; Heather had a West Indian boyfriend, unusual at the time; Gary had married at 16 after his girlfriend became pregnant; and, most scandalously, Christopher was the product of an adulterous affair Margaret had had with the dustman.

The cameras spent six months following the family in their flat above a greengrocer’s shop, and the resulting footage, edited down to 12 30-minute episodes, attracting more than 10 million viewers. It caused huge controversy due to the bad language and uninhibited discussion of subjects such as sex, race, illegitimacy and fiddling the benefits system, leading to Mary Whitehouse calling for it to be taken off the air.

At the time it was made, the Radio Times proclaimed: “The family that stars together sticks together.” But Margaret’s 26-year marriage to Terry ended a year later and all four of the children’s marriages failed. But it was Christopher, seen bursting into tears on screen as a nine-year-old on learning the truth about his parentage, who clearly suffered most. Teased at school, he went on to experiment with drugs and served a lengthy prison sentence for unspecified crimes.

Margaret claimed she had no regrets, but admitted in 2003 that the series had had a deleterious effect on their lives: “We didn’t see anything wrong with the way we lived – although other people did. When you see your life through other people’s eyes, it does change things. I might never have divorced... if it hadn’t been for the programme because Terry and I were getting along before The Family went out.”

Sylvania Waters, a BBC-Australian Broadcasting Commission co-production, was also compellingly watchable television, featuring a family (reportedly chosen by Watson and the BBC against the ABC’s wishes) who seemed to reinforce almost every possible negative Australian stereotype. Noeline Baker and her partner Laurie Donaher later claimed their lives had been destroyed by a false portrait that, through “cruel and vicious” editing, depicted them as vulgar, racist, drunken materialists. Noeline, who claimed to have been driven to the verge of suicide by the abuse they received in Australia, revealed that she would like to wring Watson’s neck.

“It was subversive,” Watson explained. “But if you’re a filmmaker, you’re meant to be subversive.” What was unclear was why the Donahers, or the Wilkinses for that matter, deserved subverting.

Stephen Paul Brooke Watson was born in London on February 17 1942 to Leslie Watson, a senior manager at the Courtaulds textile company, and Joan, née Southwell. The family moved to Bolton, Lancashire, and he was educated at Altrincham Grammar School in Cheshire.

He originally wanted to be an artist and trained at the Royal College of Art, where he mingled with the pop art crowd, but he decided he might have more success in television.

In 1966 he joined the BBC as a researcher. After producing and directing episodes of Whicker’s World, he directed the Bafta award-winning series A Year in the Life, in which cameras followed such subjects as a racehorse, a Conservative MP, a married couple, a paralysed man, a group of rockers, a curate and a farm.

Much of his work was on single documentaries and his political agenda was clear when he persuaded a group of “yuppie” City commodity brokers to let their hair down and give their unreconstructed views on everything from capital punishment to women in The Fishing Party (1985). “Thatcher complained bitterly,” Watson recalled with pride. “According to her, it was the worst documentary she’s ever seen. I suppose I should die happy.”

Watson was promoted to executive producer in 1988, then in early 1993 took over as editor of BBC Two’s ailing 40 Minutes documentary flagship. When the series was axed 21 months later, one senior colleague was quoted as describing Watson’s use of “video-diary” techniques in some episodes as “grossly irresponsible – tantamount to asking people to hang themselves in public”.

But it was the row over Sylvania Waters that was said to have led the BBC to terminate his contract. Particularly contentious was footage in which the filmmakers intercut scenes of Noeline’s daughter-in-law giving birth with Noeline at the hairdressers, shot days beforehand, making her look, as she put it “hard, harsh and unthinking”.

Watson’s later films were made mostly for Channel 4 and ITV and included The Dinner Party (C4, 1997), another tilt at the Conservative-voting classes, featuring eight friends, recruited via an advertisement in The Daily Telegraph, holding forth about blacks, gays, street crime and the “work-shy” unemployed. “Passionate views on hanging, flogging and imprisonment,” ran the press release.

Later, it emerged that Watson had steered the conversation with requests such as: “I’ve not heard enough about the dangers of new Labour.” “We do feel,” one guest was quoted as saying, “a bit set up.”

In 1995, Watson began shooting a film about Malcolm Pointon, a 51-year-old university lecturer with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, and his wife Barbara, and over the next four years he captured the couple’s tragic and sometimes violent battle with the degenerative brain condition.

The resulting documentary, Malcolm and Barbara: A Love Story (ITV, 1999), won the RTS best documentary award. He revisited the Pointons’ story in 2007 in Malcolm and Barbara: Love’s Farewell, which appeared to show Malcolm Pointon’s death but caused a furore after ITV issued a “clarification” admitting that he had died two and a half days later, and not while the cameras were rolling.

He returned to the subject of illness and death (and to the BBC) in Rain in My Heart (BBC Two, 2006), a harrowing film featuring four alcoholics, two of whom died during filming, receiving treatment at a Gillingham hospital, and exploring their individual reasons for drinking and the effect on them and their families. The documentary won a Grierson Award.

In 2003 Watson made a foray into the constructed reality genre with Desert Darlings, featuring six British couples trekking across the Namibian desert, but he did not enjoy the experience and vowed not to repeat it. He was scathing about other practitioners of the genre: “I made The Family to be socio-politically involved in a contemporary society... but reality television has lost its ability to reflect on society in anything other than a ‘Coo-er!’ way. It’s all manipulation.”

Yet he himself confessed to being manipulative: “You can’t manipulate at source. But I do manipulate in the cutting room.”

Bafta presented Watson with a special award in 2008.

In 1964 Watson married Carol Butcher, with whom he had a daughter, who survives him, and a son who predeceased him. The marriage was dissolved and in 1981 he married, secondly, Barbara Wijngaard, with whom he had two sons, who survive him. That marriage also ended in divorce.

Paul Watson, born February 17 1942, died November 18 2023