‘Pay rent or get a dose’: Central American, Haitian immigrant communities undervaccinated

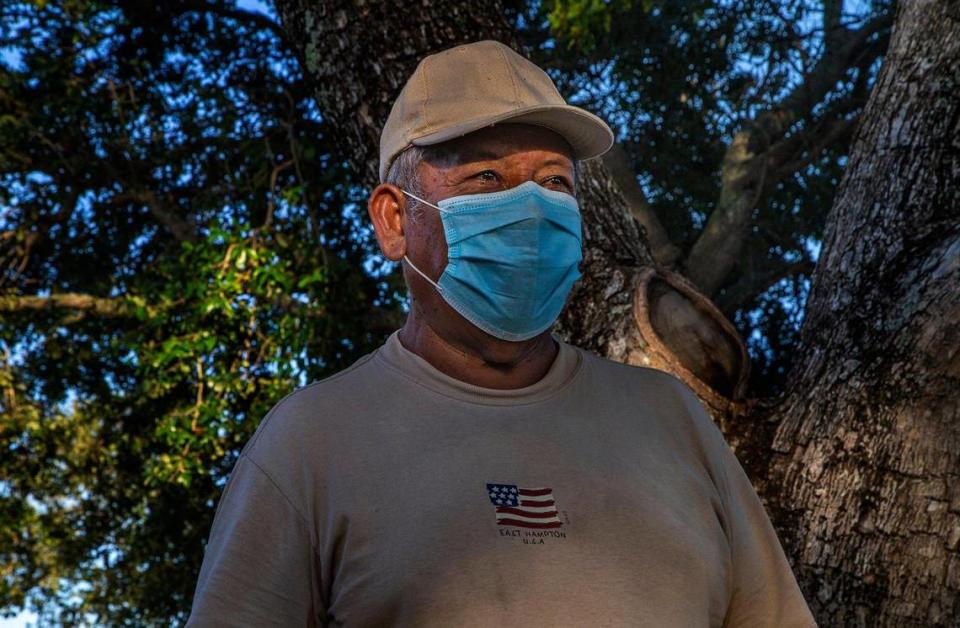

José, a 60-year-old undocumented landscaper from Guatemala, had planned his whole day off around getting a COVID-19 vaccine. (He asked the Herald not to publish his last name because of his immigration status.)

Initially, he was hesitant. Bad information about Publix charging (it doesn’t) and worries about being asked for a Florida ID (which he doesn’t have) were just some of the reasons why he initially avoided getting vaccinated. But he changed his mind when local advocates told him the pro-immigrant organization WeCount! had secured a limited number of vaccines. He got on his bike and rode to a clinic known as Clínica Campesina in Homestead. But when he arrived, no one was there. He waited, but no one came.

“We were there for an hour; there were nine of us waiting,” José recalled.

José had misunderstood. The vaccines were being offered at Centro Campesino, which was about three miles away. So he went home instead.

“I already do enough by going on my own, under the rain, on my bike, to get to work.”

José has still not gotten a dose, just like many others in communities that are home to Miami-Dade County’s most vulnerable immigrant populations — where more people tend to be undocumented, live in poverty or struggle with language barriers.

Central American and Haitian immigrant neighborhoods in Miami-Dade are disproportionately undervaccinated, according to an el Nuevo Herald analysis that used vaccination data from April 30 provided by Miami-Dade County and population estimates from the U.S. Census. By comparison, South American immigrant neighborhoods had vaccination rates significantly higher than the county’s.

By April 30, countywide 55.5% of eligible individuals (residents 16 and older) had received at least one dose, the analysis showed. But in the five ZIP Codes where the highest percentage of Central American immigrants live — where about one in every five residents were born in Central America — the vaccination rate was 41%. Those areas include parts of Homestead, Allapattah, Little Havana and neighborhoods just south of Overtown.

The disparity was even greater for Haitian immigrant communities. In the five ZIP Codes with the highest percentage of Haitian immigrants, which include parts of Little Haiti, Biscayne Park, North Miami Beach and Westview, only 32.5% of the eligible population has been vaccinated.

While more than half of Miami-Dade residents are immigrants, not all have had the same experience as Central Americans and Haitian residents born in the Caribbean. The Herald analysis showed of the five ZIP Codes with the highest percentage of South American immigrants, none had a vaccination rate below the county’s. All of the ZIP Codes had more than 90% of their eligible population vaccinated. In part of Doral, where nearly one out of every three residents were born in Venezuela, the Herald analysis showed 95% of eligible residents had received at least one dose of the vaccine. Meanwhile, the five ZIP Codes home to the highest percentage of Cuban immigrants had a vaccination rate of 51%, almost at the same level as the county rate.

No single factor explains why many in certain immigrant communities haven’t received their first dose yet, while others have some of the highest vaccination rates. Experts say it’s likely a combination of factors that make it harder for some: language barriers, lack of a Florida driver’s license and fear of using other forms of ID, transportation, an online system that is hard to navigate, and inability to take off work.

Central American immigrants in Miami-Dade tend to have less advantageous economic situations than South American immigrants, according to Jorge Duany, director of the Cuban Research Institute and professor of Anthropology at Florida International University. They also have lower levels of education and health coverage and more of them are undocumented, Duany said. That has to do, he said, with the reasons why they migrate to the United States.

Immigrants from Central America come to the United States due to poverty, extreme levels of violence in their countries, and natural disasters. Many come in through the Mexican border, without obtaining a visa, looking for work to support their families back home. Immigrants coming from South America are fleeing because of instability due to social and political unrest, Duany said. Many come with plans of starting a business, with capital in hand.

“It seems to me that it fits neatly into what we know about racial and ethnic segregation in Miami, even within the same Latino neighborhoods,” Duany said. “In a way, what we see in Miami is a sort of reproduction of the discrimination based on ethnicity and race that people bring from their countries of origin.”

He said the data analyzed by the Herald tracks with anecdotal evidence and what drives other types of inequities.

“Miami is one of the most segregated cities in the United States, where you have a different barrio for every ethnic group,” he said.

Immigration status

José Rivera, a 46-year-old Honduran immigrant who has lived in South Florida for 24 years and works as a day laborer, has been patiently waiting to get vaccinated for over a month.

It’s not because he doesn’t qualify or because he has doubts about the efficacy of the COVID vaccines, but because until a little over a week ago the state of Florida was requiring proof of residency and he’s been afraid to show up with just his farm worker ID, provided to him by a local organization.

The proof of residency requirement was waived a couple of weeks ago. The state said in part that eliminating it made it easier for undocumented immigrants and others who live or work in Florida to get vaccinated.

Erick Sánchez, who works with day laborers as an organizer with WeCount!, an organization for immigrant workers in South Florida, told the Herald that while he welcomes the move there are still many barriers in place.

“If they really wanted to get them vaccinated, they could have mobile sites, in cooperation with different organizations. We’d tell the people, and we’d get a lot of them vaccinated.”

Though a few pop-up events have occurred, Sánchez says it’s not enough.

‘This isn’t a game’

Most Central Americans Sánchez works with, who live in Homestead and North Miami Beach, do whatever day labor they can find, often in construction and agriculture. A lot of them can’t afford to take off work to get vaccinated, Sánchez said.

“Their options are to pay rent or to go get a dose, and they always choose to make some money. I don’t judge them,” Sánchez said.

But Erlyn Castillo, a construction worker originally from Honduras, told the Herald he already received one dose of Pfizer.

“This isn’t a game, this is something serious,” said the 53-year-old who says he caught COVID in March of 2020, which made him miss several days of work and he had his car repossessed as a result.

Castillo says he works seven days a week and didn’t miss work when he got his first dose and doesn’t plan to miss it when he gets his second this week.

Wendi Walsh, the president and treasurer of Unite Here Local 355, a union that represents more than 7,000 hotel, airport and food service workers in South Florida, told the Herald that about 60% of its members are still out of work as a result of the pandemic. About 40% of their workers identify as Haitian or Haitian American.

“I think a lot of people in this community are not making it a priority, when their lives are in chaos,” Walsh said of the low vaccine rates among Haitians in Miami-Dade. Hospitality workers in particular have been disproportionately affected by layoffs and furloughs.

“I think people are hearing, ‘Oh, it could knock you out for the day or two after,’ and people say, ‘I can’t afford to, I’m not going to get paid for that,’ ” Walsh said.

But Antoinette Clerisier, a Haitian immigrant who had worked as a housekeeper at The Diplomat Beach Resort in Hollywood for 18 years, lost her job a year ago because of the pandemic, and is betting the vaccine will get her closer to getting her job back.

“The only way is everybody has to take the vaccine, so places will open,” said Clerisier, 47, who lives in North Miami.

She got her second dose of the Moderna vaccine on Thursday.

Misinformation? A problem for some

Sánchez said he’s heard all kinds of conspiracy theories from migrant workers, including that the vaccine will make their crop “go bad” and that they will inject other diseases when they put the needle in. There is no evidence whatsoever that any of that is true.

To combat that, Sánchez said in March he joined a national effort spearheaded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Alianza Americas, a network of Latin American and immigrant organizations in the United States, to produce educational material about the vaccine. He’s hoping to soon get videos so he can show them on his tablet while making rounds. He said he’s pushing for them to be produced in indigenous dialects as well.

“A major part of the work we do is bring them the correct information,” Sánchez said. “They trust us, they trust me, so I have to help them.”

But Walsh said she believes too much emphasis is being put on so-called “hesitancy” and misinformation as a deterrent. She has pleaded with county officials to be included in the county’s plans to disburse federal relief funds in order to help inform the community.

“People really need a trusted messenger to encourage them to get the vaccine. The trusted messenger is not a generic physician or an elected official,” Walsh said.

There’s also many other logistical obstacles that get in the way of some Central Americans and the vaccine, according to Sánchez. Some don’t have a car and don’t have the money to spend on bus fares, and others can’t speak English or Spanish, he said, instead communicating mainly in indigenous dialects like Quechua or Maya.

Benefits outweighing obstacles

The hardest phase of the vaccination process is starting now, according to Mary Jo Trepka, an infectious disease epidemiologist and professor at FIU. Working with the people who have the most barriers to getting the vaccine should happen through local governments actually getting the vaccine to those least vaccinated neighborhoods instead of asking them to go somewhere else, she said.

Even with low levels of infection, she said, if a visitor comes infected and reintroduces the virus to the community and not enough people are vaccinated, the community could have another outbreak.

She said places of employment should be able to bring vaccines to work and encourage their employees to get vaccinated.

One ZIP Code (33034) in Homestead that had been among those with the 10 lowest vaccination rates in the county a couple of weeks ago increased its rate from 30.7% to 40.5% between April 23 and April 30. Although that’s still below the county as a whole, the percent increase was the second highest that week, only surpassed by a ZIP Code in unincorporated Miami-Dade, near the Everglades.

Zackery Good, Homestead’s assistant to the city manager, said the increase could’ve been a result of a few initiatives from that week, including two pop-up vaccination events that lasted three days at Harris Field. The Miami-Dade County-managed vaccine site Homestead Sports Complex also switched from appointment to walk-up and extended hours to run from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. beginning on April 27.

That same week, the city did outreach through social media, news release, and flier distributions. The fliers, shared with the Herald, included information about being able to use farm worker IDs as a form of identification, as well as reassurance that individual information wouldn’t be shared with law enforcement or immigration officials.

The county mayor’s office has also zeroed in on certain parts of Miami-Dade with low vaccination rates since late March. Volunteers have visited almost 60,000 homes through a program called VACS Now, talking with residents about the vaccine and attempting to get them registered to receive one through the county. Through the program more than 1,500 people have pre-registered, according to data provided to the Herald.

Rivera, the 46-year-old Honduran who didn’t want to show up to a vaccine site with his farm worker ID, has plans to get the shot with his wife this week.

Though Sánchez said most workers would prefer the one-shot Johnson & Johnson vaccine since it means having to possibly miss only one day of work, Rivera won’t be picky.

“I will get vaccinated with whatever they give me, whatever they have,” he said.

Rivera, who often talks with other day laborers about the vaccine, said although he knows he’s potentially losing a day’s worth of income, getting vaccinated is something he, and everyone else, “has to do.”

“The more people get it [the vaccine], the less the virus will be around.”

Miami Herald reporter Sarah Blaskey contributed to this report.