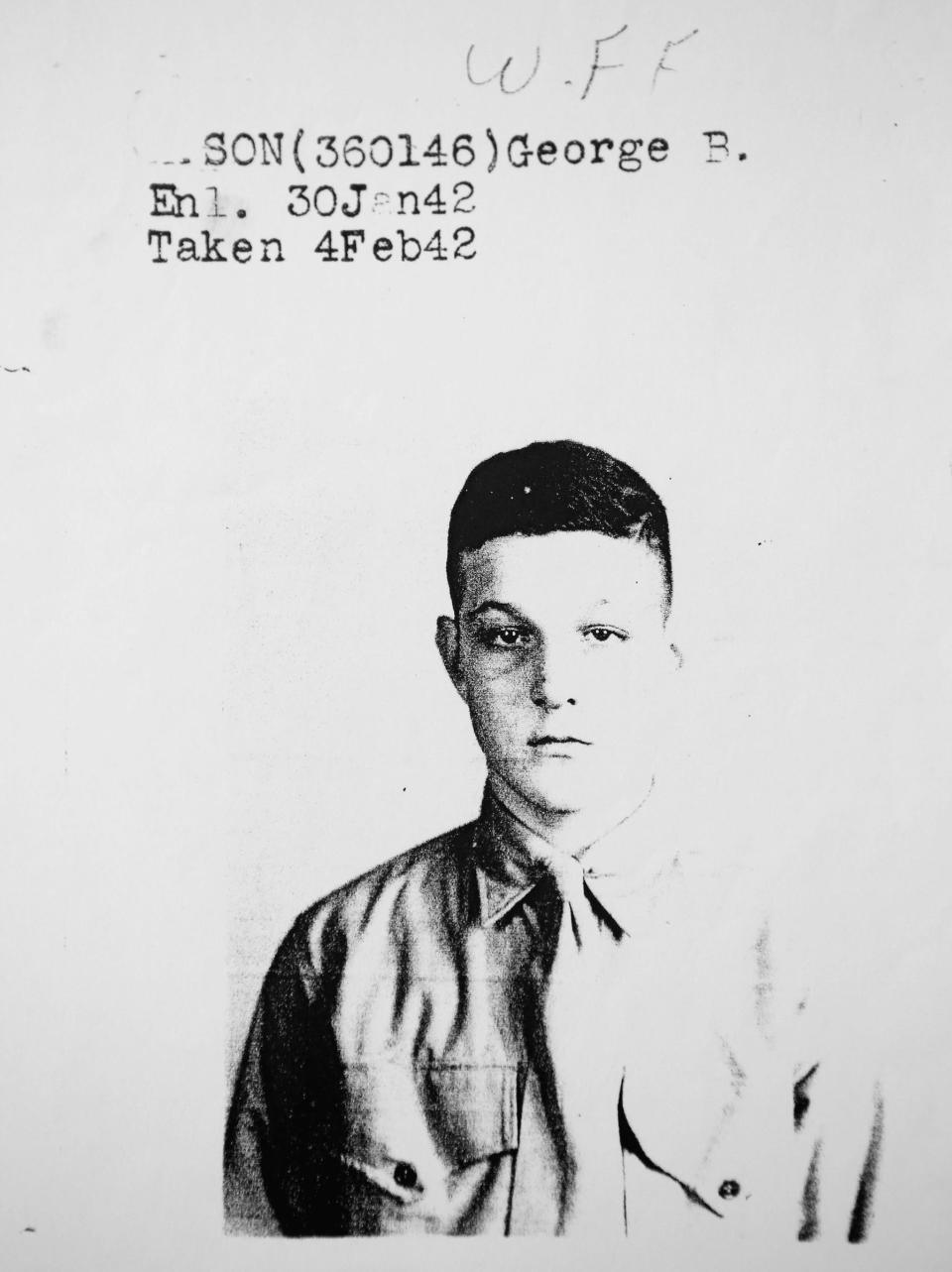

Pearl Harbor Anniversary: A cousin's death led George Mason to enlist as Marine in WWII

Editor's note: This story appeared in The Palm Beach Post on Sunday, Dec. 7, 2014.

-

George Mason rode a bicycle as a teen in 1941, delivering The Palm Beach Post and Western Union telegrams in West Palm Beach.

It was a telegram that delivered the news to his family: His cousin was among the missing on the Day of Infamy — the Dec. 7, 1941, Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor that drew the United States into World War II.

The body of his cousin, Claude Edward Rich, never was recovered. It is presumed to be among the 650 to 900 entombed in the USS Arizona, now a national cemetery resting on the floor of the harbor.

The image of that battleship, surrounded by a starburst of flame and smoke, is perhaps the iconic symbol of the attack 73 years ago today.

In a matter of hours, the Japanese killed some 2,400 and nearly crippled the great American Pacific fleet. And awakened a sleeping giant.

Among those roused to service: George Mason.

"The day I left," Mason said last month, "I made some comment like, 'I'll give them hell.' "

Right away, Mason wanted to join the fight, but he had to wait six days until his birthday. On Dec. 7, he was only 16.

Sitting last month at the Palm Beach Gardens home of a grandson's girlfriend, Mason had trouble hearing and had to stop at times to remember anecdotes. But remember he did.

History, heritage and hope:Boynton Beach honors WWII's Tuskegee Airmen

'Tough road' gets smoother:Vet rejoices as new Habitat house takes shape

A soldier's new home:Vet wounded in Iraq gifted custom-made home near Jupiter

Troubled childhood

Mason's father died of flu and pneumonia in 1929 when Mason was 4, and his widowed mother moved from Sebastian to live with her parents on 46th Street in West Palm Beach's Northwood neighborhood.

Mason's grandparents were Old Florida. His grandfather worked security for The Breakers, the Palm Beach hotel, and the couple had survived the great 1928 hurricane just the previous year.

As Mason grew, "I was kicked back and forth" between relatives, he said. "Mama couldn't handle me."

But he insisted that any trouble he got in was minor. Otherwise, he boasted, he wouldn't have gotten into the Marines.

"I was clean as a whistle," he said.

He did go to a children's home on 45th Street, he said, but he ran away. "They caught me before I got to Indiantown."

He later was sent for 18 months to northern Florida, to the now-infamous Dozier School for Boys. Researchers recently have uncovered two dozen unaccounted-for burials at the reform school.

Boys were supposed to be taught a trade there, and Mason wanted to be a bricklayer. Mostly, he said, he recalls being whipped.

Mason said boys would have to bend over a wicker chair while a piece of board drilled with holes — presumably for maximum aerodynamics — came down on their backside.

"I could not sit down for a week," he said. He said he recalled his buttocks being "purple and deeper reds. And blood. I'm talking honest-to-God blood."

Mason came back from Dozier but didn't return to public school. The Depression was on, and "if you had 15 cents in your pocket and you could rattle that, you were in good shape."

He worked for awhile as a caddie at a local golf course for a dollar or two a day and hung out with his cousin Claude Rich.

Growing up tough but gentle

The Palm Beach Post "Letters to Santa Claus" column of Dec. 22, 1930, featured this plea:

"Dear Santa: I am a little boy eight years old. My father has no work so I hope you won't forget me. I have a brother and sister older than I am and I hope you won't forget them either this year. Claude Edward Rich, West Palm Beach."

Rich was born Feb. 4, 1922, in Riviera Beach — then called simply Riviera. His father, a commercial fisherman, had a tough time making ends meet for the family at 623 46th St.

He was not a top student. He was two years older than the other 20 or so children in his class and may have repeated some years. But he was strong, and at 6 foot 2 inches, was able to play end on Northboro Junior High's football team.

"He was a nice, young, decent person," Mason said. He described Rich as a role model, "a clean-cut person. Big gob of curly hair."

Rich "wasn't direct kin," Mason said; the two were related through marriages. But at the time, extended families often shared quarters because that was all they could afford. Rich's mom and Mason's mom both lived with Rich's grandparents.

Rich, nearly three years older, "taught me to ride a bicycle," Mason said. "We'd go swimming together out at Clear Lake."

Often, he said, Rich would take him to the movies in downtown West Palm Beach for a dime each.

Other friends and relatives describe Rich as timid and gentle, not a fighter. But he had grown up rough in his tough blue-collar neighborhood, and he would stick up for neighborhood kids when bullies picked on them.

Rich landed a job delivering linens seven days a week for about $1 a day. He found time to help build additions to Northwood Baptist Church's original building at 3900 Broadway.

In 1940, Rich's father signed papers for the 18-year-old to enter the Navy, despite his mother's pleas that he remain in high school. It was not for any sense of patriotic duty or the desire to fight. Rich did it for the money, and he hoped his interest in radios would help him advance.

After Rich left, relatives used a big map to plot his movements.

He had boarded a bus for the nearest enlistment point: Macon, Georgia. He reported for duty at Norfolk, Va., on Sept. 22, 1940.

He ended up at Pearl Harbor, as a seaman first class, specializing in communications. His ship: the Arizona.

On that Sunday morning, Dec. 7, the Arizona took four direct hits from 1,760-pound converted battleship shells dropped by Japanese pilots.

At the time the deadliest shell struck, 8:05 a.m., Rich likely was in the radio room, about 50 feet from the center of the blast. It crashed through the deck beside the No. 2 turret, near the front of the ship, and into a fuel tank next to the forward powder magazine. Seconds later, 1.7 million pounds of gunpowder ignited.

Flames shot 500 feet in the air and the foremast — directly above the radio room — tilted sharply as the ship lifted up, broke apart and sank almost immediately to the bottom of the shallow harbor.

It is believed that about 1,000 of the 1,103 deaths on the Arizona — half of all killed at Pearl Harbor — occurred at that moment.

Rich likely was killed instantly.

That day, Rich's brother, Jesse Rich, also in the Navy, was home in West Palm Beach on a 10-day leave from a Rhode Island base. He and his family were sitting around the house in the afternoon. They always kept the radio on.

At word of the attack, Jesse Rich walked outside, shaken, and stood there a long while. Rich's mother cried all day but said little. His father feared the worst. About a dozen friends came to the house to offer support.

The telegram came to the house 10 days later. Mason recalls sitting on his porch when he saw Rich's parents approach. "They walked up the walk and told us they'd gotten the notice from the Navy that Claude was missing."

At Northwood Baptist Church, on a banner at the north end of the sanctuary honoring the men in the service, a star went up for Claude Rich.

Claude Rich was awarded the Purple Heart, American Defense service medal and World War II Victory medal. His parents also received a citation from President Roosevelt: "He stands in the unbroken line of patriots who have dared to die that freedom might live and increase its blessings."

Ready to 'whup the whole Japanese Army'

His cousin's death, and the attack in general, "shook me up, I'm sure of that," Mason said.

It didn't take long for Mason, along with throngs of fellow Americans, to decide to take the fight to the enemy. For Mason, there was an added incentive.

He opted for the Marines. His brother said he wouldn't like it, but "that made me want to do it much more."

Relatives "would say, 'that kid thinks he's going to whup the whole Japanese Army.' "

In fact, he said, "We all thought we'd knock them out in six months. I found out better."

Asked to elaborate, he responded, "Guadalcanal. That's enough right there."

It was a tiny island in the Pacific Ocean that most folks had never heard of in 1942. But the Battle of Guadalcanal — a torturous six months long — was the first offensive and decisive victory for the Allies in the Pacific.

The seminal engagement involved Mason's unit on Oct. 24, 1942, and their defense of a strategic airstrip known as Henderson Field. The six-month campaign centered around that airstrip, and the Marines staved off the third and final assault by the Japanese, who sought to regain control of it.

"I stayed wet 23 days with the same set of clothes on," Mason said. "Conditions was (sic) terrible, nothing but the ground beneath you and the sun over your head. And hot."

In November 1944, Mason returned stateside. The following spring, he recalled, he was at a base in California, "getting ready to go back again. 'Till they dropped it. Truman saved my soul."

Historians say an American invasion of Japan, forestalled by the two atomic bombs, would have cost thousands of American lives.

Mason came home to West Palm Beach and spent the next three decades as a roofer. Two months shy of his 50th birthday, a 65-pound roll of roofing paper dropped three stories and struck him in the back and shoulder, permanently disabling him.

"They still don't know all that broke up in me," Mason recalled.

His 64-year marriage — his wife died in 2004 — produced five children, of whom two died, as well as 20 grandchildren. He lives with relatives in Lake Park.

Of the 240 men in Mason's unit, "I'm the only one left," he said sadly.

He'll turn 90 in six days. Six days after Pearl Harbor Day.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: Cousin's death at Pearl Harbor led George Mason to join Marines in WWII