After Pearl Harbor nothing was the same: 80 years later, attack still shakes my family

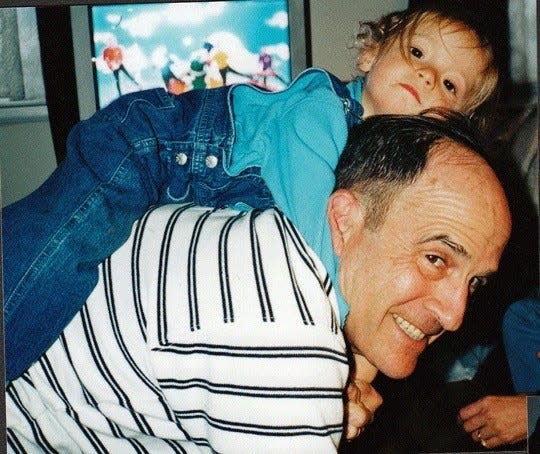

Lizzie, my then-15-year-old daughter, and my dad picked oranges. My dad was carefree as a grandfather in a way he hadn’t been as a father. In the past we had had our differences – as a teen I’d chafed against his control. While my parents planned dinner menus weeks in advance, writing them in spiral notebooks they kept for years, I snuck cigarettes in my room. When I filled their car with gas, I had to pencil the mileage and gallons of gas in a little notebook he kept for this purpose. I’d dutifully jot the information then pick up my friends and sneak into bars. I drank and drove. I did drugs. I was, in short, an angry teenager, and turned my anger both outward and inward.

But seeing my daughter and dad together over the years, from him gingerly holding her as a newborn to playing endless games of Candy Land, I newly appreciated him. Residual anger from my teenage years, woven into adult me, unwound. It took too many decades to realize he had parented the best way he knew how.

I only recently learned the reason for his need to control. Would it have made a difference when I was a teen if I had understood it then? My dad’s childhood, I learned as an adult, had more than his share of unhappiness.

One day in December

I knew something was off with my dad’s mother, Marjorie. My mom’s mother always greeted us with kisses, Kool-Aid in colorful aluminum tumblers and an exclamation: “Lawdy, you’ve grown!” Not Marjorie. The only time I remember her truly happy was when we visited Arlington National Cemetery when I was 9. My sister and I followed our parents and grandma through row after row of identical graves until we found my grandfather’s. She gently rubbed the stone and smiled.

Back home, she quietly sang “Tiny Bubbles,” reliving (I assumed) a more joyful time. Was she reminiscing about life in Hawaii with her husband before everything fell apart?

One December day in 1941 my dad, Bobby, then 16 months old, toddled around the house at Schofield Barracks Army Base, following his 3-year-old sister, Barbara.

As they played, Marjorie’s husband prepared for work. Robert was in his mid-30s from a poor family in rural Mississippi who later attended West Point.

More than 50 years after the war, I read several of the V-mail letters he had sent to his children from Europe. It was clear he was a hands-on father, something I suspect was unusual during that time for a lieutenant colonel. I like to think he played horsey with Bobby and Barbara, as, years later, my dad would for my sister and me, and many years after that, my dad would for Lizzie.

Then everything changed. Planes zoomed above their house and dove low. At first, they thought it was just practice. Then they saw the planes were Japanese and the smoke rising from nearby Wheeler Army Airfield. “Noise!” My dad, Bobby, screamed. Planes shot Schofield Barracks and bombed adjacent Wheeler field to prevent its planes from defending Pearl Harbor, 15 miles south. While Marjorie calmed the children, Robert rushed to defend the base.

Thrust into war

After Pearl Harbor, nothing was the same. They were evacuated to Honolulu and then, with eventually 20,000 other women and children, evacuated from Hawaii.

Robert stayed at Schofield until 1942, preparing for a Japanese invasion. Eventually, he and the family moved to West Point. Bobby and Barbara soon had a new sister.

Then in the summer of 1944, a few months before my dad turned 3, Robert was deployed to Europe. Of six sisters, my grandmother Marjorie was the “delicate” one. Aware of this, Robert wrote reassuring notes about being far from the fighting. He sent quite different letters to his mother.

“You may tell Margie whatever you think she should know. However, I don’t want her to do any worrying about me." Robert wrote from southern France after describing heavy fighting he had seen at Hurtgen Forest, the scene of some of the war’s bloodiest battles, and later, from the Battle of the Bulge.

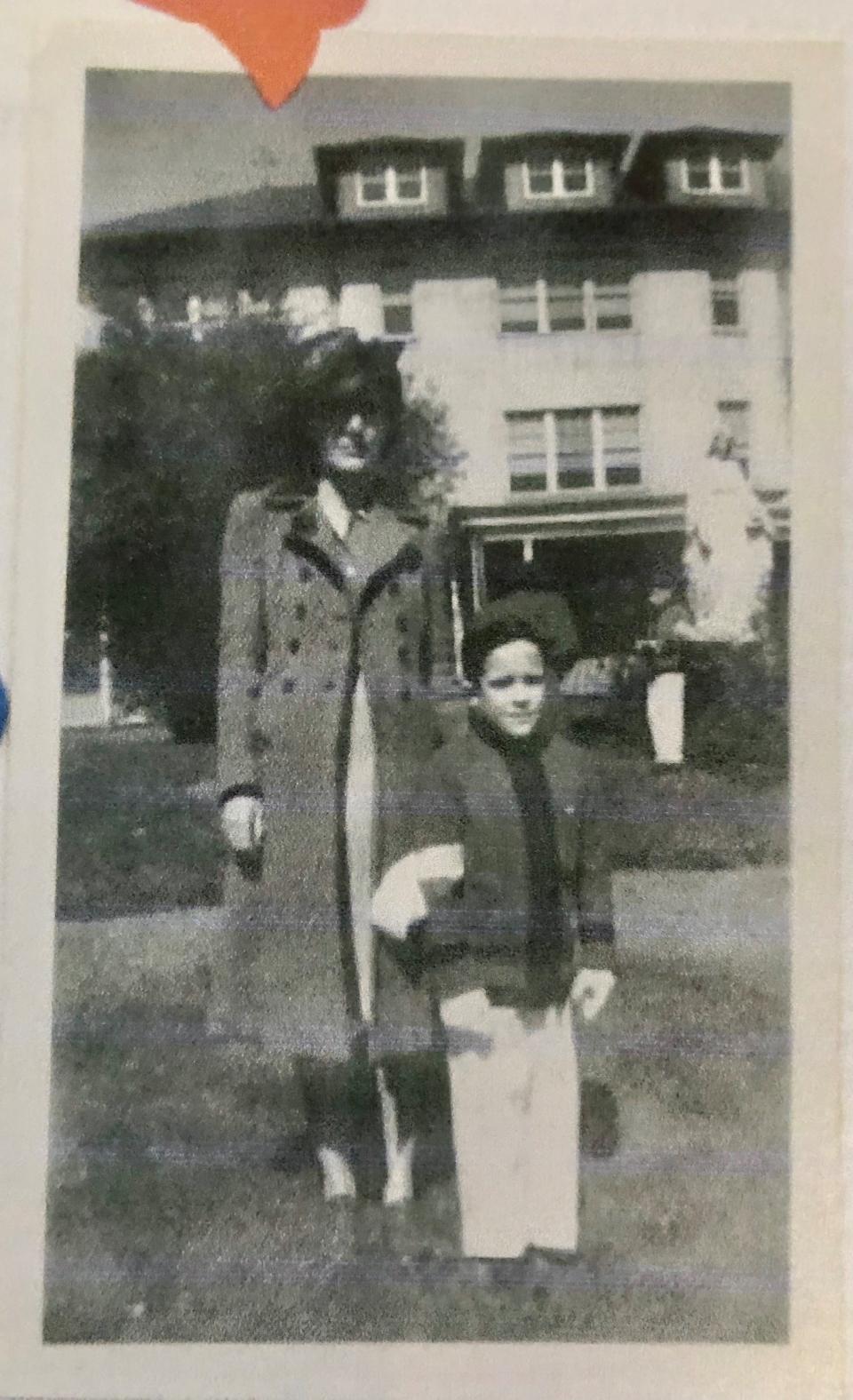

He had reason to protect her. While Robert was leading his battalion, despite buffering the truth to his wife in letters home, Marjorie was having what was most likely a nervous breakdown. She must have been overwhelmed, with three small children. She probably knew Robert was sending an edited version of his life. While she recuperated, she sent Bobby and Barbara, who were 4 and 6, to a Catholic boarding school and had relatives care for the baby. They were in boarding school two years.

About a week after Robert wrote his mother about the Bulge, he was in Holland. He stepped on a land mine going through an abandoned German trench. His men survived. In an instant, he became a hero and his wife a widow.

Barbara overheard two nuns talking about her father’s death. She pretended she hadn’t heard anything and like a horrendous nightmare, waited for them to tell her and Bobby. What was it like to hear the news this way? My dad was 4, too young to grasp the finality of death. They stayed at school and grieved on their own.

A phantom emotional leg

I recently asked my dad what he remembered about his father. He said, “I was so little I don’t remember much. I have a warm feeling – I think he was warm and loving.”

“How do you think it changed you?” I asked.

“I don’t know any other reality. I guess it’s like when someone is born with one leg, they don’t know what having two is like.” I think he’s minimizing it, in the same way Robert did with his letters to Marjorie.

Of course, Barbara and Bobby received no counseling. Nor did my grandmother. They never talked about what had happened. My dad said whenever they asked, Marjorie changed the subject. They grew up hobbling around on one emotional leg, never learning what it might be like to walk with a prosthetic limb.

Is it any wonder, then, that my dad didn’t want to get too close to anything emotionally uncomfortable, that he wanted to schedule his entire life to avoid surprise? He had had his life upended by the worst surprise of all. He had mourned alone and learned that uncomfortable feelings should be tucked away.

War changes not just those whose lives were affected by it, but its effects also trickle through generations. My grandfather’s death didn’t affect just Marjorie and their young children; it touched those who weren’t yet born. When I was a kid, my dad never talked about his early childhood – it was as if it had been redacted. I learned about it only a few years ago from my cousin.

Like my dad, I spent a long time keeping my emotions under lock and key, scared to let them loose. As a teen, I muted them with booze and rebellion. Even now, four decades past my angry teen years, I’m not big on surprises. It affects my husband and daughter.

Eighty years after Pearl Harbor, its impact still reverberates through our family.

Sue Sanders is a writer and the author of "Mom, I’m Not a Kid Anymore," a parenting memoir.

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Pearl Harbor 80th anniversary: Attack upended my father's life