Penfield man investigates rare book found in CVS bag. Could its value reach six figures?

There are many things that Nick Rozanov's father did not leave behind. Stories forgotten, photos never seen, memories unrecorded: the eternal regrets of children after their parents pass on.

Mikhail Rozanov did, however, leave two interesting items. The first is a small yellowed receipt from the Manhattan bookstore Dauber & Pine for a purchase made Feb. 17, 1969. Three dollars and 15 cents, plus 41 cents tax.

The second is the book that Mikhail Rozanov bought that day: a rare alternate version of the first edition in Russian of Karl Marx's "Das Kapital," the foundational text of communist thought. It's possible there are fewer than five copies in the world.

"I remember he told me: 'You'll be able to put your kids through college with this," said Nick Rozanov of Penfield.

The book itself is the handiwork of a 19th century Russian spy who fostered the growth of the leftist Russian émigré community in New York City even while sabotaging it in service to the czar. He printed a very small number of copies of the book and then surreptitiously destroyed most of them before they could be smuggled into Russia.

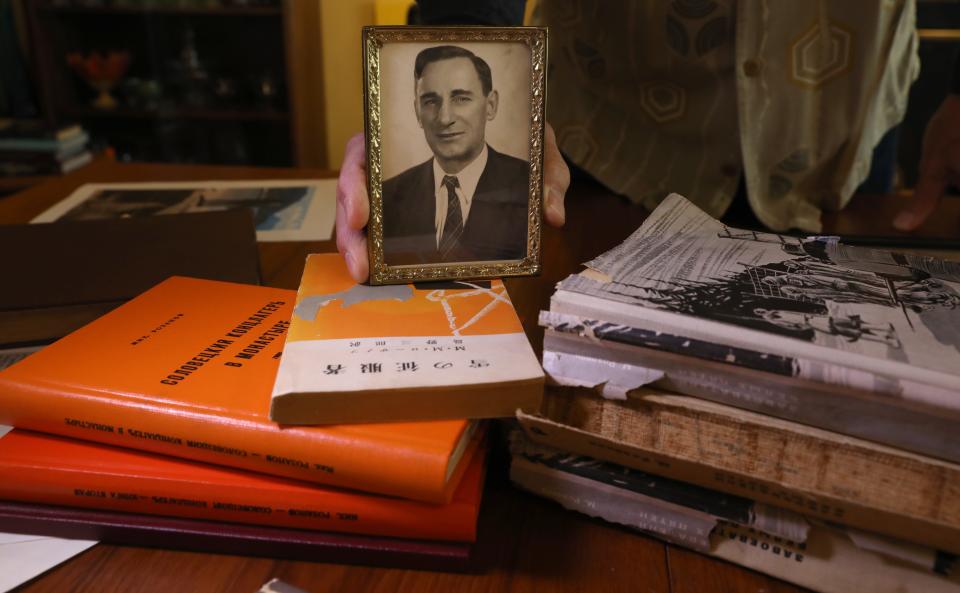

It exists today thanks to the sharp eye of Mikhail Rozanov, a Soviet reporter who did 13 years in a prison camp for an ill-timed act of rebellion before moving to Buffalo and taking a job at Bethlehem Steel. At some point he also wrote several well regarded books on the Solovki gulag where he was imprisoned.

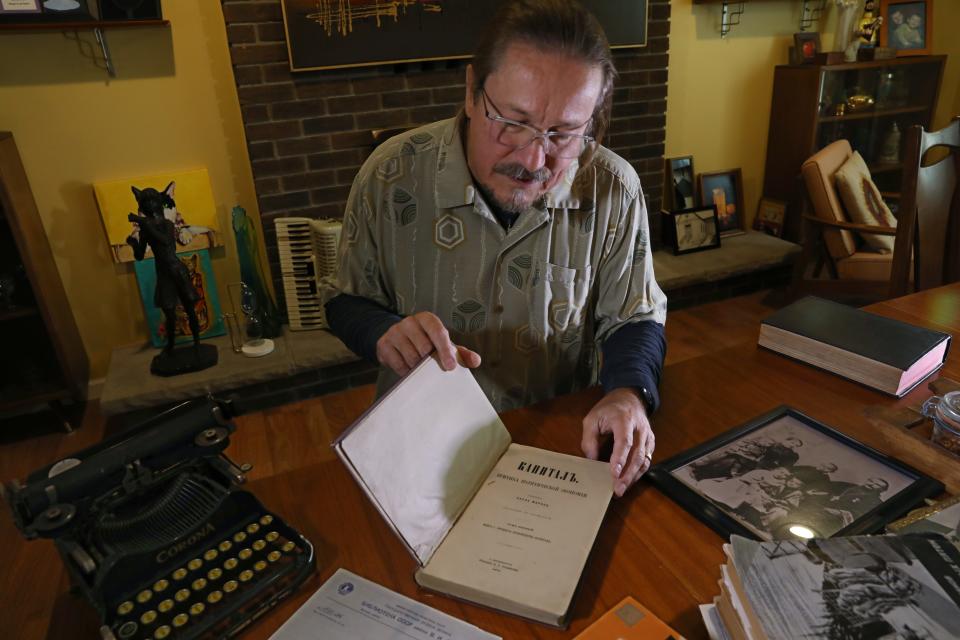

The elder Rozanov's legacy is recorded — or so his son assumes — in the crates of books he left behind and in particular in his own personal papers. They're mostly written in Cyrillic handwriting that would be nearly illegible even for a fluent Russian speaker, something Nick Rozanov is not.

"This one, you can recognize it from his initials: M.M.R.," he says, pointing to the cover of one yellowed volume, pushing a strand of his long hair out of the way.

That's another thing Nick Rozanov recalls his father telling him: Don't let your Russian language lapse. He followed the advice only in part.

It served him well in his career as a radio career, where he was plucked serendipitously from a Buffalo rock station to open the first joint American-Russian radio station in Moscow. It was one unexpected stop among many, all chapters of a tale he tells with great gusto.

This is his retirement project: restoring his father's legacy, sorting through his papers and finding the proper place for his towering stacks of books.

The Marx book and some other valuable ones are locked away, secure and out of sight.

So, too, is the story of Mikhail Rozanov.

"When I was younger, people would always kind of point and whisper: 'That's Michael Rozanov, he's a very esteemed writer, a very respected person,'" Nick Rozanov said. "And that's pretty much all that I know about it."

A spy in New York

How did a pirated work by the world's most famous Communist become, more than 100 years later, a gem in the thoroughly capitalistic world of rare books?

It started in 1867, when Marx first published "Das Kapital" in German. Five years later a translation appeared in Russia; the censors of Czar Alexander II allowed it despite Marx's inflammatory message, assuming that most Russians would find it incomprehensible.

Three thousand copies were printed and quickly bought up. There was great demand within Russia's leftist community for a second printing, but the government recognized its initial mistake and banned further distribution.

For Russian dissidents, the problem was not unusual. They had a well-practiced workaround: smuggling in more copies from abroad.

"It was actually considerably easier to print something outside of Russia, put it on a ship and smuggle it in than to run a printing press within the country," said Lorne Bair, a rare book seller in Virginia who specializes in leftist political history.

Here they turned to Alexander Evalenko, a well known émigré socialist bookseller and publisher in New York City. In 1897 Evalenko brought an original copy of the Russian translation of the book to a printing house and made a copy of it. There are few discernible differences between the 1872 Russian book and the much rarer 1897 New York book; one is a slightly different typeface Evalenko used on the title page.

The publisher distributed a few dozen copies to socialists in New York City and purported to ship the rest to Russia, where they could be smuggled across the border.

But Evalenko was not just a stalwart of the radical Russian community in New York City. He was also working for the czar, spying on the very Russian-American leftists among whom he lived and worked.

Evalenko faithfully reproduced all his correspondence with American leftists and sent copies back to the Russian government. He did so for 20 years before finally being exposed in 1911.

The Marx books he printed were, by design, intercepted and destroyed.

The few samples of "Das Kapital" that he distributed in New York City, then, are the only versions that escaped destruction by Russian censors. And it must be one of them that Mikhail Rozanov stumbled upon 70 years later in a Manhattan bookstore.

Cock-and-bull stories

Mikhail Rozanov wasn't party to any of that intrigue. He was born in Russia in 1902 and by 1923 was working as a journalist for Tass, the Soviet news agency.

In 1928 he fled over the border to Manchuria, now part of China.

"I thought it was the job of journalists to tell the truth, (not) to write cock-and-bull stories of the 'wonders' of Soviet existence," he later wrote.

But his timing was poor: in 1929 the Soviets invaded the part of Manchuria where Rozanov had landed. He was captured and sent to Solovki, a forced labor camp on an island in the remote White Sea.

Solovki was to become a template for the Russian gulag system. Rozanov spent 13 years there and in other camps. He described constructing military installations in the whipping Arctic cold, "practically with our bare hands."

As an educated prisoner, he was also given a relatively comfortable assignment as a bookkeeper, Nick Rozanov said. That combination of firsthand experience and inside data became the foundation for his life's work of exposing the brutality of the gulag system.

"The free world cannot imagine the important role slave labor is playing in building up the Soviet military machine," he wrote in a freelance news article in 1950 after immigrating to the U.S. "These large and easily movable labor armies have to be provided with only a minimum of food and clothing, a roof over their head and the necessary tools. Fear will keep them at work."

Rozanov was liberated from Soviet control only after the outbreak of World War II. He was taken to Germany as a Nazi prisoner of war, then finally freed in 1945. Four years later he came to the United States.

His first job when he arrived was picking grapefruit in California, his son said. Then he heard about a sizable Russian population in Buffalo and moved there to work for Bethlehem Steel.

Heads or tails

That's the story that can be pieced together from Mikhail Rozanov's sparse online record. One biographical website says he was "considered one of the best pre-Solzhenitsyn historians of the Gulag system," with one of his books becoming "a post-war bestseller among Russian readers outside the USSR."

Nick Rozanov never knew about all that. Actually, he still doesn't.

His own memories of his father, who died in 1989, are more limited — mostly, that he was always researching and writing.

"It was a small North Buffalo steelworker's house and it was just filled from floor to ceiling with books," Nick Rozanov said. "That was just normal to me growing up."

He's got copies of five books his father wrote but his Russian isn't strong enough to read them. One is printed in Chinese, something he's not at all prepared to approach.

The Marx book fits in there somewhere, too. It was wrapped in a CVS bag and stashed in the back of a bookshelf. Nick Rozanov wants to learn more about it, including its possible value.

He has a letter that his father received from the USSR's Ministry of Culture in 1971, reporting that experts there knew of only three extant copies in the world at the time.

How much is it worth, then? Impossible to say. It seems possible that this particular edition of the book has never changed hands publicly.

The most expensive copy of "Das Kapital" ever to sell at auction was a first edition signed by Marx. It went for $309,000 in 2016.

Bair, the subject matter expert, said Rozanov's copy likely belongs in a rare books library somewhere.

"This is the major theoretical work of Marxism," he said. "It’s a hugely important document and any evidence of the ways in which it was disseminated among the global Russian revolutionary class is of great interest."

And then there are Mikhail Rozanov's own papers. Crates of them, mostly written in that illegible Cyrillic hand. Who knows what story they tell, about Russia and the gulag and perhaps about the man himself.

"I have so much of his research," Nick Rozanov said. "But I've got to make heads or tails of it."

Justin Murphy is a veteran reporter at the Democrat and Chronicle and author of "Your Children Are Very Greatly in Danger: School Segregation in Rochester, New York." Follow him on Twitter at twitter.com/CitizenMurphy or contact him at jmurphy7@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Rochester Democrat and Chronicle: Rare copy of 'Das Kapital' by Karl Marx investigated by Penfield man