Pensacola's skateboarding scene goes back generations. A new skate park excites them all.

When the skateboarding scene first started taking off in Pensacola, people looked at Freddy Esposito and his ilk as outlaws.

When Esposito started skating in the early 1970s, he and his friends would use the streets as their playground, finding abandoned swimming pools, ditches and other unique places to ride.

The city's original skateboard spot was between First Baptist Church Pensacola and the Days Inn by Wyndham Pensacola off Palafox Street. The roads and parking lots surrounding Florida Square were wide and new, and riding them downhill was like surfing a big wave.

The possibilities of what skaters could do there were endless, and the area went from having 15 people to 150 skating on a given Friday night.

Esposito lived close to the Tanyard and the trip up to it was easy. So easy, it was basically his second home.

"I graduated in '73, on the night I graduated, I went to prom. I had a tuxedo on and some (Chuck Taylor) All Stars," Esposito said, reflecting on his early days of skating. "I went skateboarding in my tuxedo that night before I went to my prom. That's how (big a) part of my life it was."

For Esposito, his friends and the generations of skaters who came after, skating was not about being outlaws. It was about community, belonging and having a good time.

Construction set for Pensacola skatepark: After seven years, construction set to begin on $2.1 million downtown Pensacola skate park

Paved Wave reunion: Paved Wave flashback: Pensacola skating pioneers reunite

"It was fun. I'd love to come up with a better reason," said Esposito, now 66 years old. "It was just so much fun to hang out with my friends. We played music and it was just fun. No one was trying to change the world. We're just trying to be good at what we did and have fun with it."

Pensacola has long had a skateboarding culture, and in fact was home to the second skate park in Florida, the Paved Wave.

Paved Wave was closed in 1979, and since then, skateparks have been few and far between in Pensacola.

But the city's skate culture has endured, and with the new Blake Doyle Skatepark under construction, new generations of skaters are keeping the community and the culture of skating alive and well.

Paved Wave generation

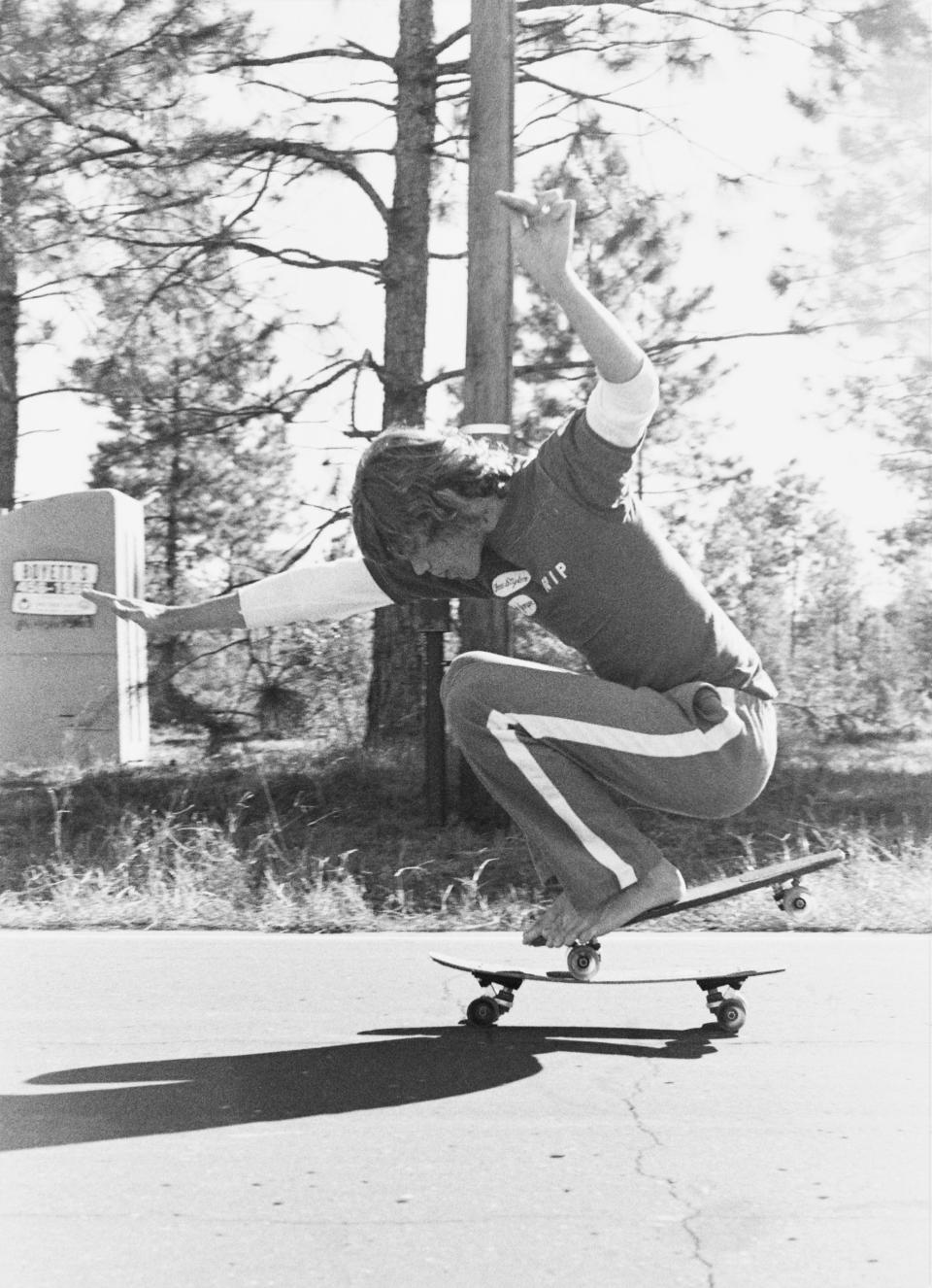

Rip Hanks was part of the Paved Wave generation.

At the time, many surfers were exchanging their surfboards for clay-wheeled skateboards and practicing their surf moves on concrete instead of water.

The 61-year-old remembers his first time hopping on a skateboard and riding it on the sidewalk at 6 years old, thinking it was the coolest thing ever.

He picked up skateboarding again when he was 13 and by age 15 he had set a record for a skateboard high jump.

Hanks and his friends would participate in competitions and do a lot of slalom skateboarding, downhill racing and freestyle skateboarding — doing a routine of multiple tricks in a row in an allotted amount of time.

This meant doing a lot of basic as fast as possible, because speed and creativity earned you points.

"One of the cool things about skateboarding is that it's a very individual sport that you enjoy with a lot of people," Hanks said. "So, you learn a lot about yourself. It's a lot of failures before you have any successes and everybody's encouraging you."

Esposito first began skateboarding in 1970 when he and his friend brought some skateboards because they wanted to be as good as the rest of the surfers around. It was all about speed and grace back then.

He also made his way into competition skating, and he was approached by two men at an event who had been contracted to build a skate park in Pensacola. They wanted Esposito to be the manager to look over the construction of the park and help make sure no one would hop the fence and get hurt.

At the time, Esposito was making surfboards and he decided to take the job.

Esposito wanted to build a skateboard community in Pensacola and felt that local skaters were just as the ones in California where the sport originated.

The Paved Wave Skate Park was ultimately opened in 1976 near the Goofy Golf course on West Navy Boulevard.

At the park, going from a 30-foot ramp into an 18-foot bowl and transferring from that bowl into another bowl allowed a person to feel like they were surfing, hence the name.

Hanks remembers that a big thing was being in the bowls and getting as many of the wheels out of the bowl as possible while at least one wheel stayed inside on the ledge.

Tricks like kickflips, ollies and 360s weren't possible on their clay-wheeled boards, but when polyurethane wheels hit the streets, "getting air" became the new thing to strive for.

The skate park was hugely impactful, but short-lived. It folded in 1979 amid safety concerns, liability issues and an inability to keep up with demand for the latest accessories and gear.

When Paved Wave closed, skating in the area started to go "rogue," as Hanks and his friend started to build their own ramps, find empty swimming pools or go to other cities like Panama City to find a skate park.

Nowadays, Hanks sees the acquisition of a new skate park as a way for skateboarders to have a place to have fun, find friends and build a community of people from all different backgrounds.

And despite the decades since the Paved Wave's closing, Esposito is proud of how the sport has grown and how the new generation have finally got a new skate park in the area.

"When skateboarding first came out, it never caught on. It was more like the hula hoop. It was just another toy that the kids played," Esposito said. "So for us, and for me personally, to see all this happening, it just makes me proud. I'm more like a proud parent than I am excited about it, because I had something to do with it and I've watched it grow up."

Last obstacle: Pensacola skate park just needs to ollie over one last obstacle. But it's a big one.

Budget boosted: Pensacola skate park clears last big obstacle after council OKs budget boost

New generation

A few hundred feet from where Pensacola's skate scene originated, a new skate park will be built under Interstate 110 along North Hayne Street, between Jackson and La Rua streets.

The new Blake Doyle Skatepark will be modeled similarly to the iconic West L.A. Courthouse Skate Plaza in Los Angeles that became a popular spot for skaters because its ledges were perfect for skateboarders to grind and slide on.

The person who spearheaded the new park's creation is Jon Shell.

Skating has been a part of Shell's life since he was a kid. Shell and his friends were already riding around on skateboards when they were in elementary school. He even started to build ramps in his driveway when he was in fifth grade.

Shell's neighbor, Scott Stanton, gave him one of his first skateboards when he was starting off. Stanton's parents, who had other children who skated, supported Shell's skateboarding endeavors and Stanton even shared old VHS tapes of him skating.

He played other organized team sports, but the thrill and autonomy of skateboarding was always close to Shell's heart.

"Is it an art or is it a sport? Well, my answer is yes," Shell said about the beauty and rigor of skateboarding.

Even while skate parks were few and far between as he was growing up, he always wanted to bring one to his hometown of Pensacola. He saw there was a skateboarding community in need of one.

In 2015, he created a blog series called "Forgotten Youth" that outlined the need for a skate park. Eventually he and his friends created Upward Intuition to help raise money for the endeavor. The plan was to name it after Blake Doyle, a beloved friend known for uplifting others.

After seven years of raising money and getting approvals from the Pensacola City Council, the $2.1 million skateboarding park is on its way to fruition. It will be part of the first phase of the $25 million Hollice T. Williams Stormwater Park, connecting the neighborhood around the I-110 overpass with downtown.

Skater Katie French said she was excited to finally have a skate park coming to Pensacola.

The 25-year-old started off skateboarding with a Walmart skateboard when she was in middle school but after two concussions decided to rollerblade. French has used skating as a form of meditation during tough times in her life — she could put her earphones in, turn her music up, drown out the world and just skate until she pushed all the weight of her shoulders.

After being introduced to more people in the area who skated, she realized how supportive everyone was.

"I realized that the skate community was a community that welcomed creativity, diversity. It welcomed all of these incredible minds, and everyone could come together and just enjoy skating," French said.

She was very enthusiastic to join a group called Pensacola Grrrls Skate Society where she has not only made friends with other women who skate, but has helped other young women with an interest in it. Groups like this have helped her and other girls navigate a male-dominated sport and give them space to have fun and feel supported by "other women who will pick you up."

Skating has always helped remind her she has ambition. Her knees and elbows are scarred from the failed attempts at skate tricks. She has learned to pick herself up and keep going, hopefully with a story to tell her future grandkids about what she used to do, how those scars came to be and how they made her tougher.

"Skating has given me confidence," French said. "That is the biggest thing, because I get down on myself a lot. A lot of people do. And skating has given me that confidence in that understanding that I deserve to be here and I'm worth being here."

This article originally appeared on Pensacola News Journal: Blake Doyle Skatepark will bring skaters from all generations together