GE's pension freeze puts a spotlight on America's retirement planning problem

The news that General Electric (GE) was freezing its pension for 20,000 workers this week and offering buyouts to 100,000 former employees sent the company’s beleaguered stock up slightly, but dealt the two fierce blows to two great American institutions.

The first: GE itself. An American staple and iconic industrial company that has employed hundreds of thousands — if not millions — of Americans over the years and paid benefits loyally to its workforce showed yet another flicker, like the incandescent bulbs it famously made.

The second: the American pension.

It’s no secret the private-sector pension is on its last breaths. Over the past 20 years, the percentage of Fortune 500 companies that offer a traditional pension plan has fallen from 59% to 16%, according to Willis Towers Watson. Pension plan freezes have been on the rise as well.

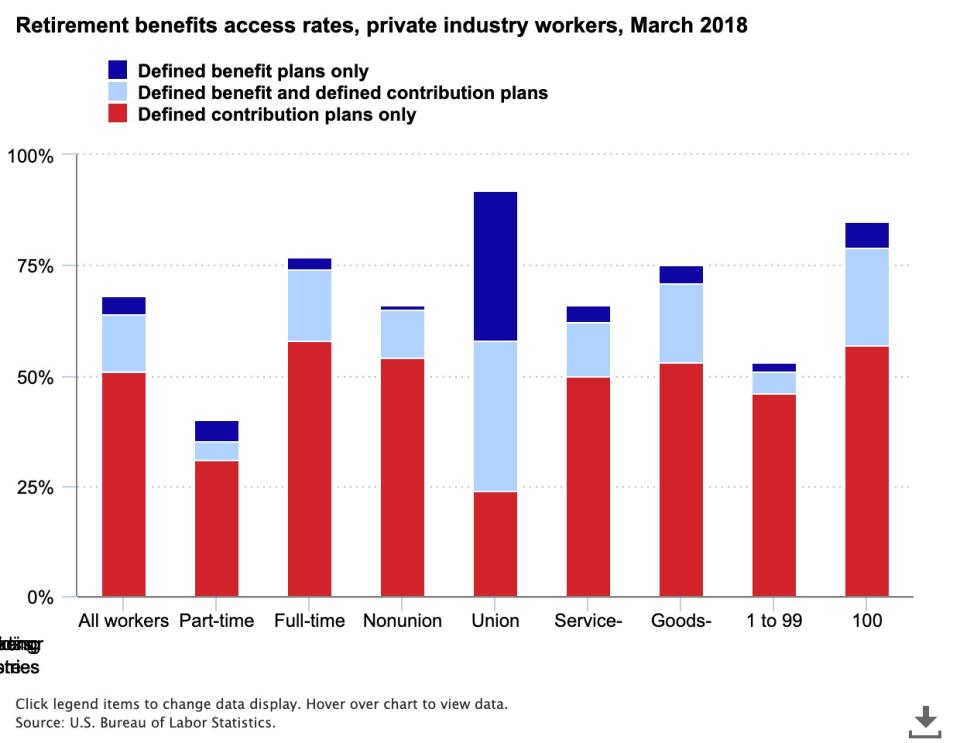

For the entire workforce, only 4% of today’s workforce has access to a traditional defined benefit pension plan, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

But the fact that GE, the shining example of a one-company-for-life, is shelving the practice and pushing the existing employees into 401(k)s is one of the last nails in the coffin for this retirement planning option. Similar corporate titans like IBM (IBM) and Boeing (BA) ceased pensions in the 2000s.

In the post-pension world, the risk shifts to the employee

Pensions and 401(k)s both provide means to save for retirement and to pay money out, but the way they accrue money has one key difference: who owns the risk and responsibility of investment management.

For a pension, the company and employee pay into a pool of money. Then the company invests that money and hopes that it’s enough to pay a defined benefit when the employee retires. If the company isn’t a successful investor and the money in the portfolio doesn’t grow enough, the company has to pay the difference out of its own profits. According to JPMorgan Asset Management, the last 10 years have seen the funding of top pensions drop from over 100% (assets to liabilities) to around 84%.

For a 401(k) however, the individual takes on all the risk. They must do all the investing and administrative work, and then must hope the market gods smile down on them and that the amounts they decide they can take out every month are enough to live on — but not too much so they’ll run out.

With the death of the pension comes a great big hole in the American concept of retirement, a hole leaves stress and uncertainty.

Companies have been pivoting towards 401(k) plans for quite some time, as it’s much less costly. In many respects, it makes a lot of sense. Particularly because it’s portable. Workers don’t stay at one company their entire working lives anymore — they jump around and need a retirement framework with savings that can follow them.

A long life is now a ‘risk’

As Brookings fellow and pension expert. Mark Iwry, has noted, “longevity risk” of outliving your savings presents an extremely challenging dilemma. How can you use a life expectancy table, when there’s a 50% chance you will end up on the wrong side.

The 401(k) and IRA plans may offer people means to mimic what pensions have done in the past, but in addition to placing the risk of investment failure on employees and retirees, they also place the work. In their glory years, pensions were ingrained into company culture. In the case of GE, the company’s famously generous pension was sometimes a key reason people chose to work there. Contrast this with today. Many companies offer 401(k) plans and many of them even automatically enroll employees into them and match contributions up to a point.

But the default amounts are generally small, say 3%. This means that it’s entirely up to the individual to decide to invest more. Though the “how” is often made easy by target date funds, the risk rests squarely with the employee.

The 401(k) shortcomings aren’t currently being addressed in any meaningful way in Washington, though the encouragement of 401(k) auto-enrollment and government’s efforts to motivate people to save like the Saver’s Credit have helped plug the hole in the past. In 2017, one of these programs, the “myRA,” which was billed as a retirement plan for anybody, was phased out by the Trump administration, which cited limited demand.

That’s not to say there aren’t solutions being proposed. Though they rightfully have a terrible reputation in many cases, some experts like Iwry see some sort of consumer-protected annuity as a potential answer. But for that to work, there would need to be widespread encouragement of these products to create the demand required to have competitive prices and features.

But this doesn’t exist yet. Until then, Americans who someday hope to stop working have to live with the difficulties and stick with the model in place. They pay, they work, they hope.

-

Ethan Wolff-Mann is a writer at Yahoo Finance focusing on consumer issues, personal finance, retail, airlines, and more. He is reporting from Berlin on the Arthur F. Burns fellowship from the International Center for Journalists. Follow him on Twitter @ewolffmann.

Social Security phone scams are now a greater threat than IRS scams

Beyond Meat is learning a big lesson in Germany

‘Flight shame’: A potential headwind for airlines in Europe

Read the latest financial and business news from Yahoo Finance

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, LinkedIn, YouTube, and reddit.