Pentagon Papers leaker weighed morality of A-bomb at Cranbrook, months before Hiroshima

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Months before the U.S. dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima and revealed to the world the existence of nuclear weapons, a ninth grade class at Cranbrook was given an essay assignment on the morality of such weapons of mass destruction.

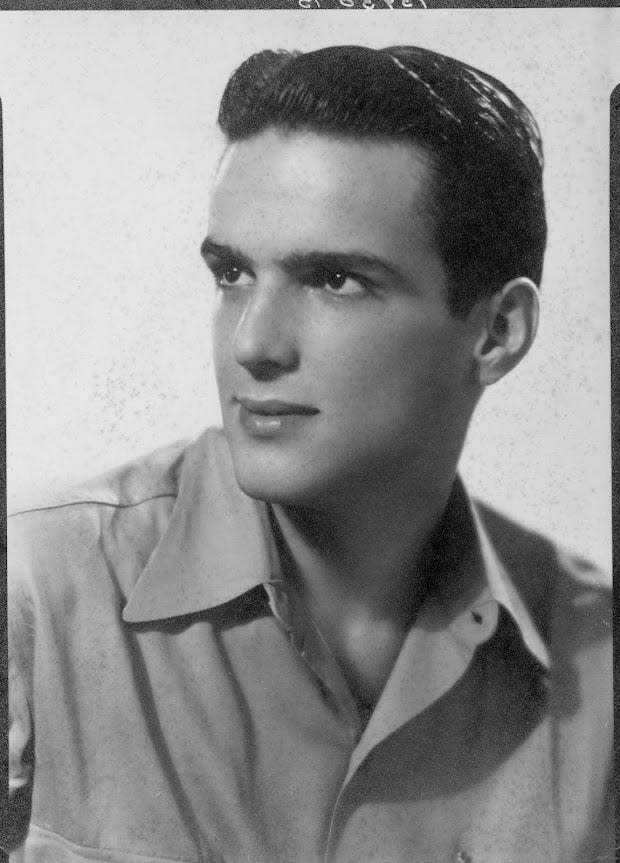

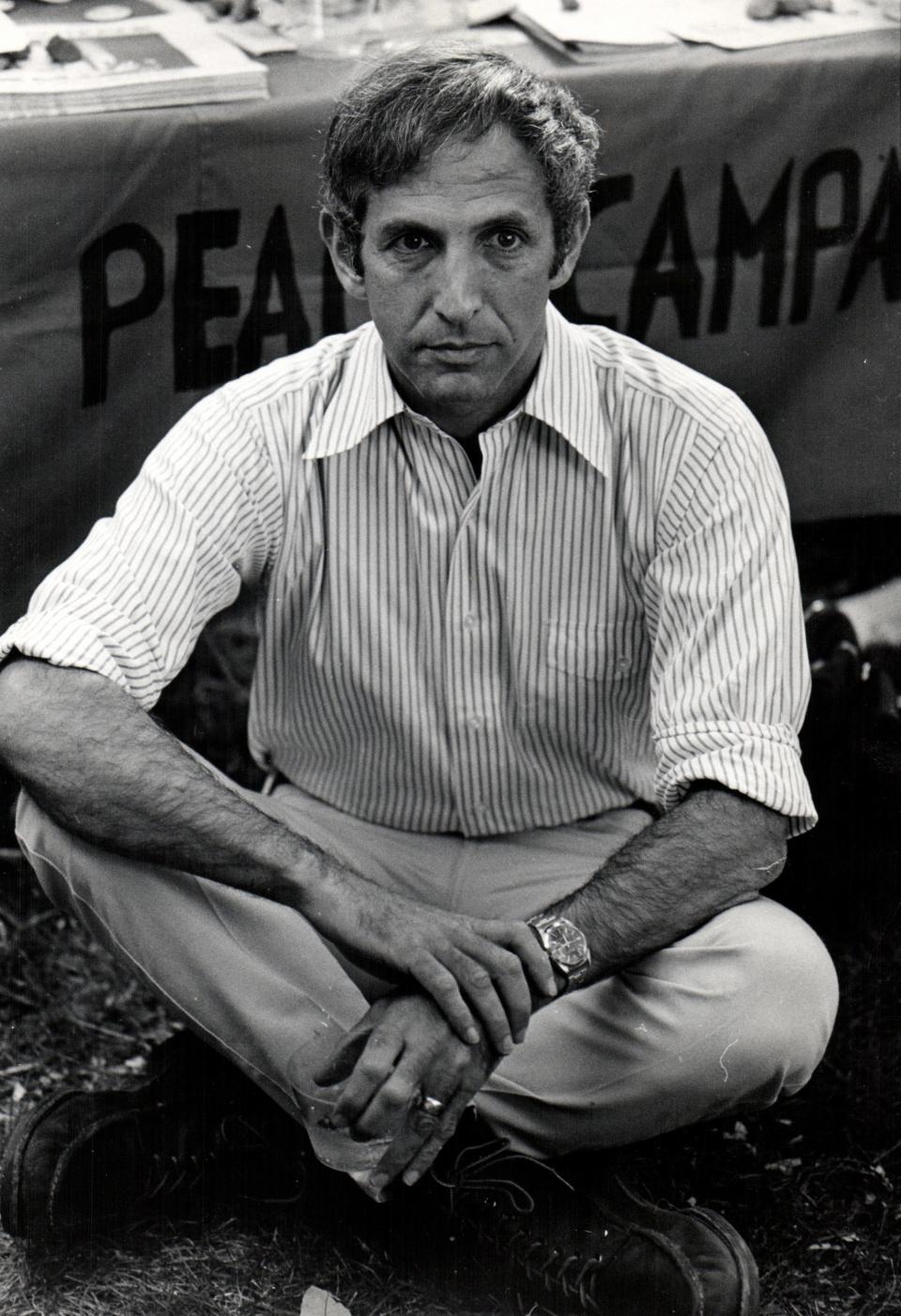

One member of that class in fall 1944 was 13-year-old Daniel Ellsberg, who would decades later become famous for leaking the Pentagon Papers secret history of the Vietnam War.

The class' teacher was a young man who had recently arrived at the Bloomfield Hills private school from the University of Chicago, which, two years earlier, and unknown to the general public, had become home to the first nuclear reactor.

As Ellsberg recalled in his 2017 book, "The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner," the teacher explained how it was now possible to conceive of a bomb made of a U-235 uranium isotope that was far more powerful than any existing bomb and could destroy an entire city.

But what about the implications for humanity? Would such a bomb be good or bad for the world? And would it ultimately be a force for peace or for destruction?

The students were told to write their thoughts in an essay, due the following week.

The unique circumstances of that class assignment — occurring well before the July 16, 1945, Trinity atomic bomb test and Aug. 6 dropping of the "Little Boy" bomb on Hiroshima — has fresh resonance this summer.

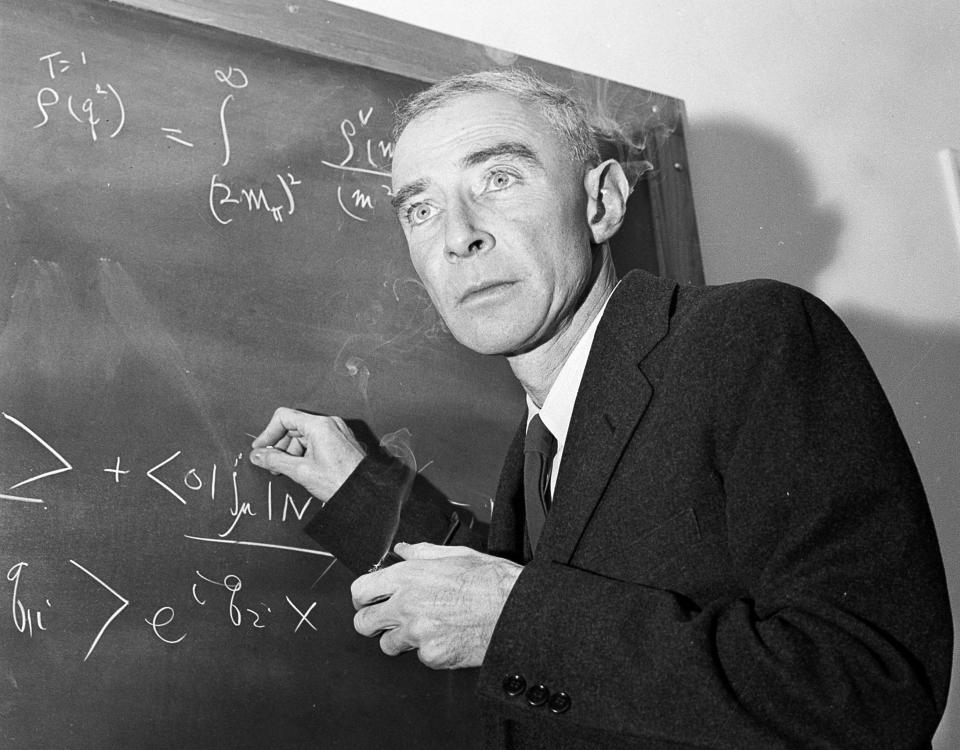

The new movie "Oppenheimer," about the life and personal struggles of J. Robert Oppenheimer, known as "the father of the atomic bomb," is a major box office hit. And Ellsberg, whose illegal disclosure of the Pentagon Papers informed the public about government deceptions and nearly landed him in prison, died June 16 at age 92.

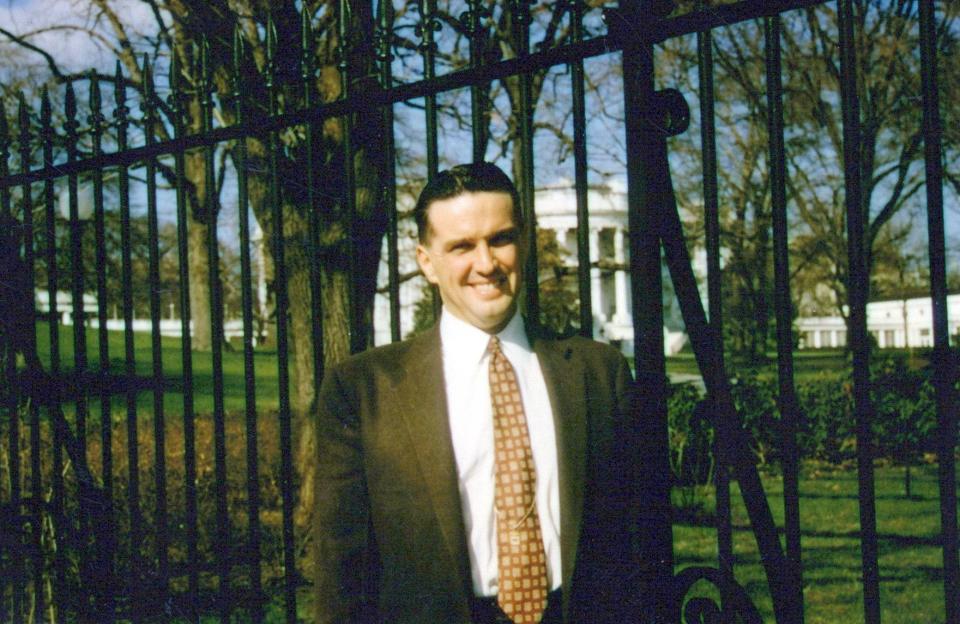

The teacher of Ellsberg's ninth grade social studies class, Bradley Patterson Jr., was at Cranbrook for only two years. He went on to a succession of positions in the U.S. government, including roles in the Dwight Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford White Houses. He altogether wrote three books about the White House staff.

Patterson was born in Massachusetts and was turned down for service in the U.S. Army during World War II because of a punctured eardrum. After receiving bachelor's and master's degrees from University of Chicago, he met a Cranbrook representative who was visiting campus to recruit teachers for the Michigan school.

Ellsberg makes clear in his book that Patterson wasn't spilling any nuclear secrets to the class, but rather utilizing niche yet generally available knowledge about the theoretical possibility of atomic bombs that could be found in science publications.

For Ellsberg, whose Jewish family lived on Winona Street in Highland Park, the experience in Patterson's class set him and his classmates apart from most other Americans at the moment when they — and the rest of the world — first heard and read of the reality of nuclear weapons. At the time, Highland Park was still a prosperous small city and Ellsberg's father worked as a structural engineer who helped design the Ford Willow Run Bomber Plant.

"Perhaps no others outside our class or the Manhattan Project ever had occasion to think about the bomb — as we had, nine months earlier — without the strongly biasing positive associations that accompanied their first awareness of it in August 1945," Ellsberg wrote. "That it was 'our' weapon, an instrument of American democracy, developed to deter a Nazi bomb, a war-winning weapon and a necessary one — so it was claimed and almost universally believed — to have ended the war without a costly invasion of Japan."

'Cultural lag'

Ellsberg attended Highland Park public schools before he started at Cranbrook in the seventh grade. He skipped the eighth grade and was on full scholarship and a boarding student by the ninth grade, according to the book.

The subject of an atomic bomb came up in Patterson's class as part of a discussion about the sociology concept of "cultural lag," coined by William Ogburn, which is how technology innovations move faster than other aspects of society, such as the ability to control the new technology wisely.

As Ellsberg recalled, Patterson shared how it may be possible to create a bomb with the U-235 uranium isotope that could be 1,000 times more powerful than the bombs being used in the war. Such a bomb was an example of a technological development that was a leap ahead of existing social institutions.

In his own essay for the class' assignment, Ellsberg remembers writing how such a powerful bomb wouldn't be a good thing — regardless of which country got it first.

"As I remember it, everyone in the class arrived at much the same judgment. It seemed pretty obvious: The existence of such a bomb would be bad news for humanity," Ellsberg said. "Mankind could not handle such a destructive force. It could not be safely controlled."

More: Daniel Ellsberg, the Pentagon Papers leaker, had roots in metro Detroit, Cranbrook Schools

More: Before seeing 'Oppenheimer,' learn about Detroit's involvement with the atomic bomb

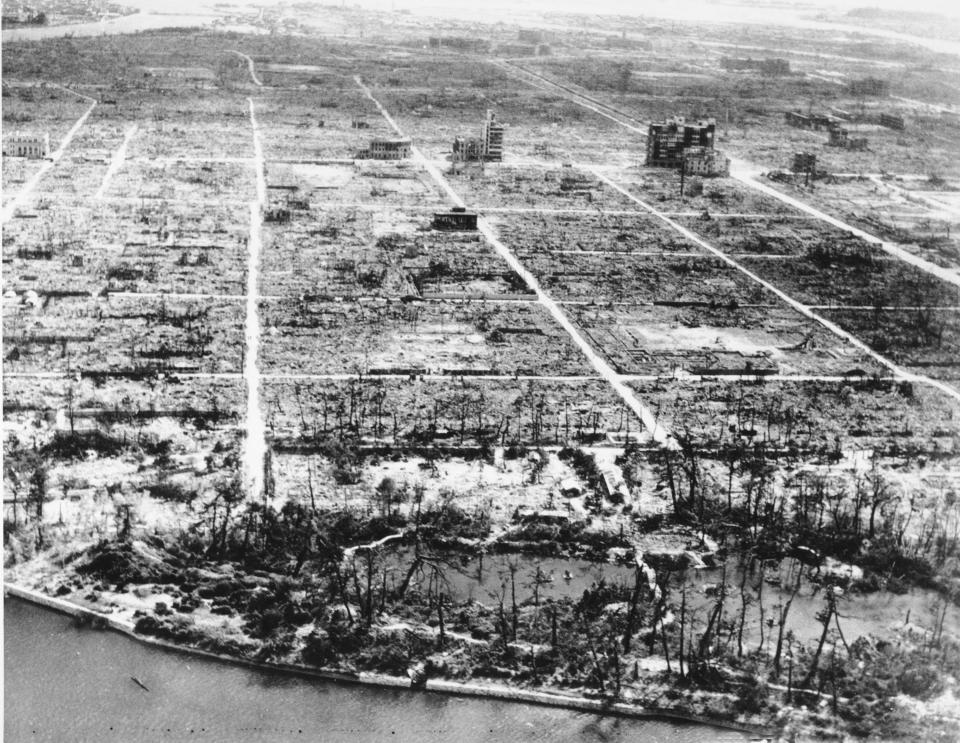

Ellsberg recalls in the book how he was standing on a downtown Detroit street corner on Aug. 6, 1945, when he saw Hiroshima on the front page of the Detroit News.

"A streetcar rattled by on the tracks as I read the headline: A single American bomb had destroyed a Japanese city. My first thought: 'I know exactly what that bomb was.' It was the U-235 bomb we had discussed in school and written papers about the previous fall."

He then experienced a "sense of dread," he wrote, "A feeling that something very dangerous for humanity had just happened. A feeling, new to me as an American, at 14, that my country might have made a terrible mistake. I was glad the war ended nine days later, but it didn't make me think that my first reaction on Aug. 6 was wrong."

The following year, Ellsberg's mother and sister were killed in a car crash. His father was driving and had fallen asleep at the wheel.

Young Ellsberg also was in the car and bashed his head against a metal fixture. He suffered a broken leg, broken ribs and was in a coma for 36 hours, according to Tom Wells, author of "Wild Man: The Life and Times of Daniel Ellsberg."

'It's metallurgy'

His teacher, Bradley Patterson, died in March 2020 at age 98.

In a phone interview last month, his son, Glenn Patterson, told the Free Press that his father enjoyed teaching at Cranbrook and remembered Ellsberg well. His two years at Cranbrook were the first and only time that his father resided in Michigan. After the 1944-45 school year, the elder Patterson moved to Washington, D.C., for a job in the U.S. State Department.

While most of the atomic bomb's development happened at Los Alamos, New Mexico, an early scene in the movie "Oppenheimer" shows the first artificial nuclear chain reaction occurring in December 1942, within a squash court under the football stadium stands at the University of Chicago.

Glenn Patterson said that his father, who was then at the university, recalled how the student body knew something was up.

“I remember him relating how all the students knew that some very special experiments were going on," he said. "Whenever anybody asked about it, they were told ‘it's metallurgy.' That was all they got.”

His father and Ellsberg had occasional contact over the years. On one occasion Ellsberg accepted Bradley Patterson's invitation to speak at his Unitarian church in Bethesda, Maryland.

Glenn Patterson said he believes his father was proud to have had Ellsberg as a student.

"He didn’t take any credit for shaping Ellsberg’s political philosophy or anything like that, but he did just feel pleased that one of his students had the conscience to do something like that," he said, referring to the disclosure of the Pentagon Papers.

On to Harvard

After graduating from Cranbrook in 1948, Ellsberg went on to Harvard College on scholarship, served in the U.S. Marines and later received a doctorate in economics from Harvard.

He worked as a government consultant with the RAND Corp. in the late 1950s and into the 1960s, including on nuclear planning. His clearance was several levels above Top Secret.

In his 2017 book, Ellsberg recounts how in addition to copying the documents that became the Pentagon Papers, he copied a separate set concerning U.S. nuclear policies. These papers had information that Ellsberg felt should be publicly known, such as threats for nuclear strikes made against U.S. adversaries and how nuclear weapons were secretly stored aboard ships in Japanese ports.

The documents also showed how military plans for potential nuclear war against the Soviet Union included automatic nuclear strikes on Chinese cities.

Ellsberg recounted a meeting of his planning team with two admirals who were dismissive of the team's suggestions about the possibility of a decision by the president to go to war against just the USSR — and not China, too. One admiral responded that it would be insane to go to war against only one communist power "while letting the other one off scot-free."

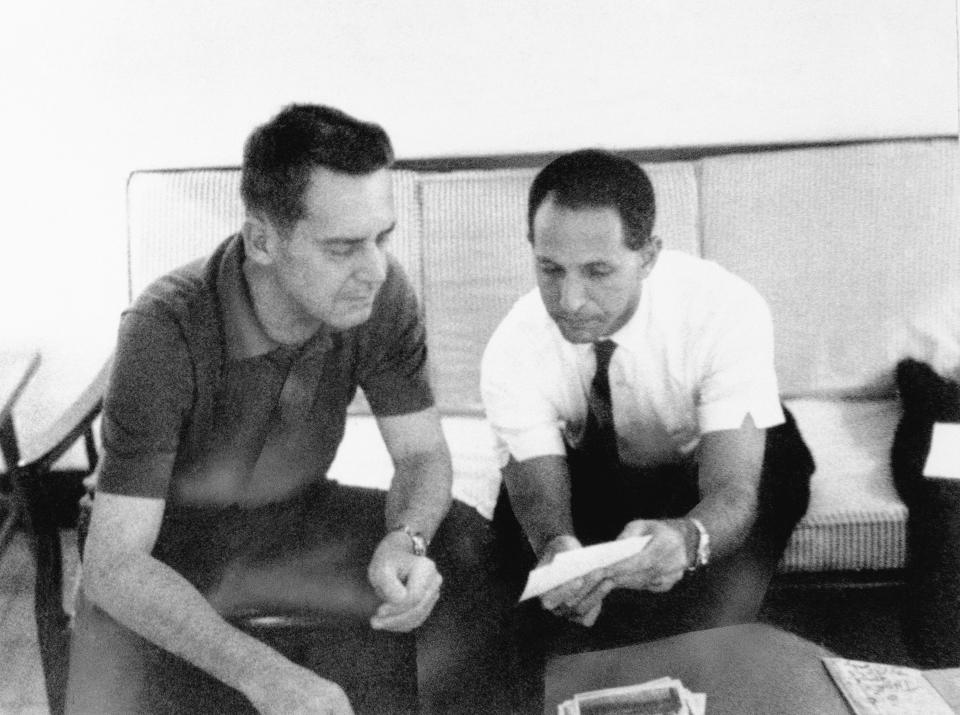

In 1964, Ellsberg became an adviser to U.S. Defense Secretary Robert McNamara and spent months on the ground in Vietnam evaluating the conflict. According to the New York Times, McNamara later summoned Ellsberg and 35 others to produce a history of U.S. involvement. That project became the Pentagon Papers.

From insider to dissident

By 1969, Ellsberg was disillusioned with the Vietnam War and attending antiwar protests. He was especially moved by draft resister Randy Kehler, whose example set Ellsberg on his own path from government insider to dissident and peace activist.

Ellsberg said he spoke with Kehler in November 1969, shortly before Kehler reported to prison. He asked his opinion about leaking the Vietnam documents or the nuclear secrets first. Kehler suggested the nuclear secrets.

"By this time, we know all we need to know about Vietnam," Kehler replied, according to Ellsberg. "What you reveal about that won't make a difference. From what you tell me, you're the only one who can warn the world about the dangers of our nuclear war plans. That's what you ought to put out."

Ellsberg agreed that the nuclear documents were important, "but Vietnam is where the bombs are falling right now. If I put it all out now, including the nuclear material, the press won't pay any attention to the history about Vietnam. I think I have to give that as much of a run as I can first, for whatever difference it might make to shorten the war. Then I'll turn to the nuclear revelations."

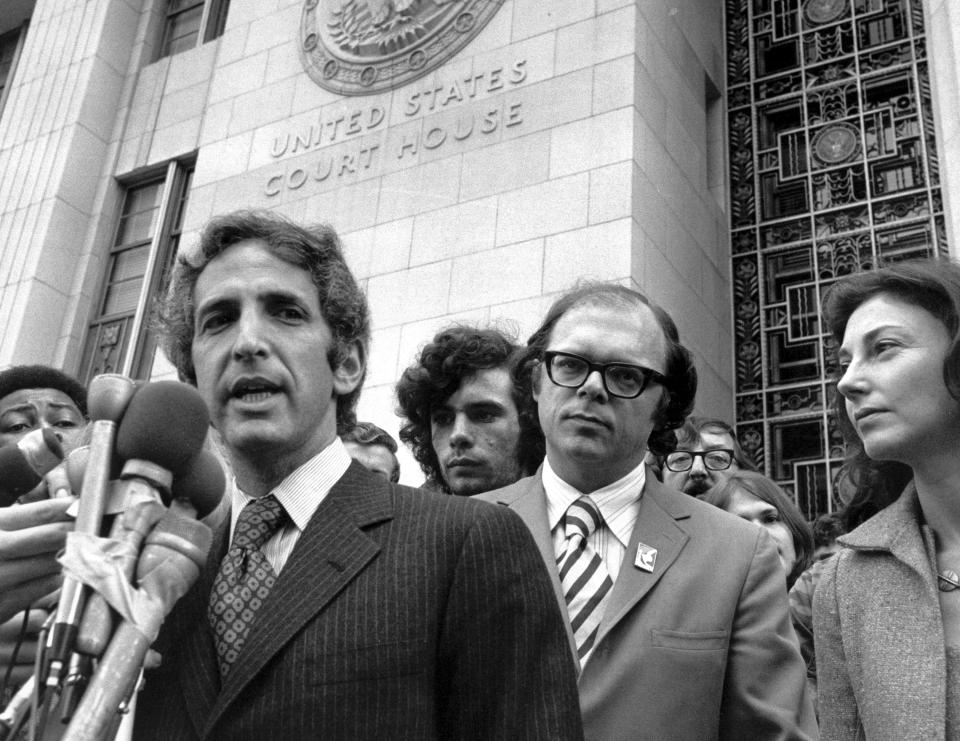

Ellsberg went on to leak the Vietnam documents in 1971, first to the New York Times and then other newspapers, including the Washington Post. Those Pentagon Papers chronicled years of deception by government officials about the war and prospects for a U.S. victory.

He then was indicted on espionage and other crimes and faced a possible prison sentence of over 100 years. Ellsberg decided it was best to hang onto the nuclear papers for publication after the trial.

The government's case against Ellsberg fell apart amid revelations of the Nixon administration's misconduct in pursuing him, including burglary of his psychiatrist's office in an effort to steal his medical records. He was then free to go.

Nuclear papers disappear

Ellsberg's subsequent plan to leak the nuclear papers was ultimately thwarted by bad weather.

For safekeeping, he had given the documents to his brother, Harry. The brother put them in a cardboard box inside of a garbage bag and buried them in his yard in Westchester County, New York. But after neighbors spotted men probing around the yard, the brother moved the box to a spot near the town trash dump.

Then Tropical Storm Doria hit and the papers washed away, according to the book. They never were found.

However, many of the same documents were eventually declassified over the decades through Freedom of Information Act requests by researchers and book authors.

No country has exploded nuclear weapons in combat in the 78 years since the U.S. dropped its bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki to end World War II. And so far, there has been no World War III.

Yet Ellsberg contends in his book that countries that possess nuclear weapons use them all the time.

"U.S. presidents have used our nuclear weapons dozens of times in 'crises,' mostly in secret from the American public (though not from our adversaries). They have used them in the precise way that a gun is used when it is pointed at someone in a confrontation, whether or not the trigger is pulled. To get one's way without pulling the trigger is a major purpose for owning the gun."

Contact JC Reindl: 313-378-5460 or jcreindl@freepress.com. Follow him on Twitter @jcreindl.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Pentagon Papers leaker gained insights into A-bomb at Cranbrook in '44