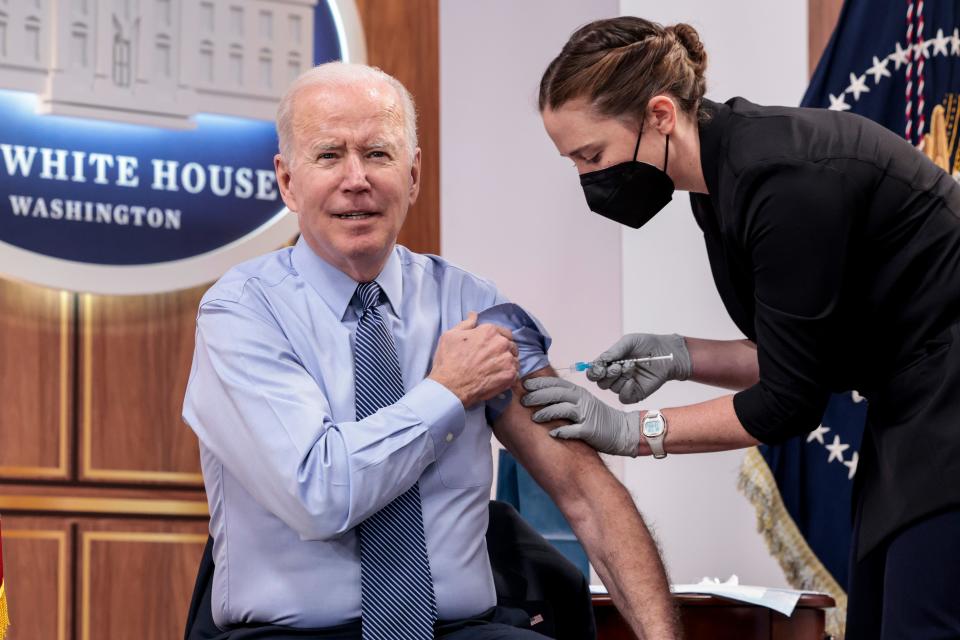

People 50 and older are eligible for a second COVID booster. Who should get one?

Many people who've been supportive of COVID-19 vaccines all along wonder whether they should get a second booster.

Last month, the government authorized an additional booster for anyone 50 and older whose last shot was more than four months ago. But just because an extra shot is permitted doesn't mean everyone should get one, health experts say – at least not yet.

For those with a healthy immune system, the first two doses dramatically reduce the risk of death from COVID-19. Studies show a third shot likely takes severe disease off the table, too, even with omicron, which swept across the world and infected roughly half of all Americans.

But scientific research doesn't offer much guidance on a fourth shot, and the decision has to be highly personal, experts said.

Studies don't yet indicate the benefit or duration of fourth shots or drill down into different age groups or categories of people. That led the U.S. to allow second boosters for people 50 and older, while in Europe, second boosters are limited to just those 80 and older.

The current course of the pandemic adds to the confusion.

Recorded cases are climbing a bit again, but have been near historic lows in the United States. Meanwhile, they're spiking in China and remaining relatively high in parts of Europe. Predictive models suggest the U.S. will almost certainly face another wave this fall and winter when respiratory viruses are usually at their worst.

This matters, because if there's not much virus circulating, the risk of exposure is lower, as is the need for a booster. But if exposure risk is high, more people may need an extra dose.

Data also suggest protection from vaccines fades within months, and even people who were infected won't be protected forever. Getting a fourth dose now may mean the need for a fifth later in the year.

So, how should eligible people know whether to get a booster sooner or later, or whether to get one at all?

USA TODAY asked or heard from more than a dozen experts in the past week and compiled their – sometimes contradictory – advice.

There's one thing all the experts agree on: initial vaccine doses provide great protection against severe disease and death from COVID-19.

"These are fantastic vaccines," said Dr. Daniel Griffin, an infectious disease expert at Northwell Health in New York.

Griffin said he's concerned the constant talk about boosters makes people question the effectiveness of vaccines, when they shouldn't.

"It does not help us," he said, "as far as trust and vaccine uptake going forward."

Latest COVID news: New COVID omicron subvariants are spreading across New York. Here's what to know

Who should consider a second COVID-19 booster?

Another area of expert agreement is that people who are older or with many health problems – and especially people who are older and have lots of health problems – should get a fourth shot as soon as possible.

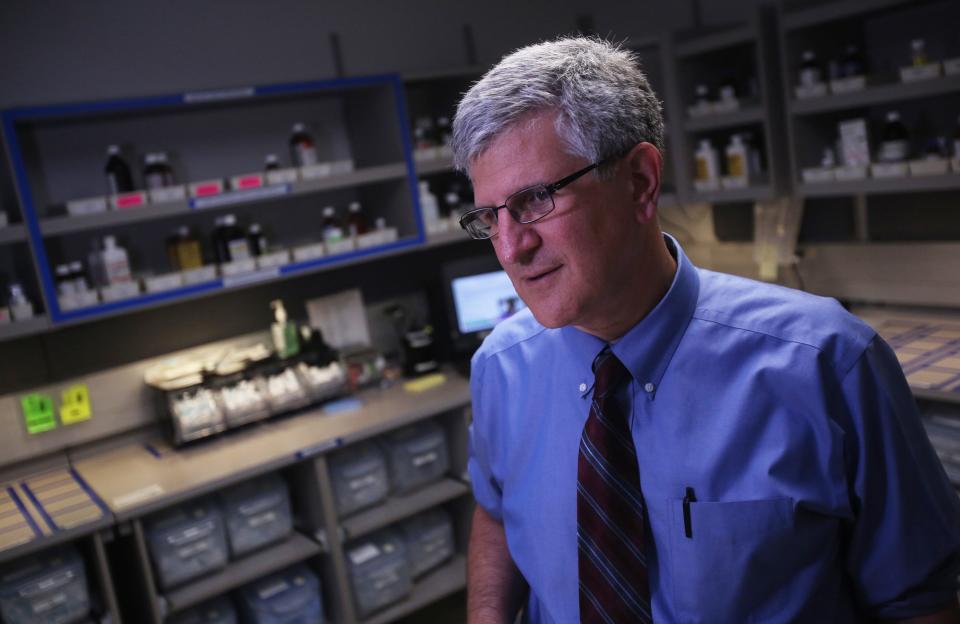

Even Dr. Paul Offit, the vaccine expert who deems most of the current "boostermania" unnecessary, said people over 65 with health issues should get extra shots, along with younger people who are significantly immune compromised.

An immune system that doesn't work well, because of age, illness or medication, won't respond as well to vaccination as a healthy person.

In one study from late last year, people who were hospitalized with COVID-19 despite having been vaccinated were likely to be over 65 and/or to have high blood pressure, diabetes or obesity. (The study also found that 85% of those hospitalized had not been fully vaccinated.)

Griffin said he recently suggested to a 70-something patient with a lot of medical problems that he should get an additional shot. But for a healthy 50-year-old patient who had bad side effects after the other three doses, he advised holding off on a fourth.

Still, he said, if COVID-19 cases start rising again in the fall or winter, it may make sense for more people to get boosters to reduce their short-term risk of even mild infections and to help limit spread.

What vaccines can and can't do

Experts are increasingly asking what the Biden administration hopes to accomplish with COVID-19 vaccines.

When the shots first became available, manufacturers and officials talked mostly about how much disease they prevented. That set the expectation vaccines were going to stop all COVID-19 infections.

But that was never realistic, said Offit, who directs the Vaccine Education Center at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. No vaccine against a respiratory virus has ever been shown to prevent all infections, he said.

As variants appeared, and particularly with omicron, vaccines stopped preventing less severe infections – though they retained their ability to prevent severe disease and death.

A Food and Drug Administration advisory committee last week concluded that the goal shouldn't be to block all infections.

"Our focus is on preventing hospitalization and death," committee chairman Dr. Arnold Monto said in ending the eight-hour meeting. "We don't feel comfortable with multiple boosters every eight weeks."

At some point, he and others said, effort and money could be better spent on something else.

"I'm willing to believe there are some people in whom the (booster) shots are doing some good," said Dr. Phil Krause, who left the FDA's vaccine division late last year. But "if you look carefully, the real benefit is in a very small proportion of the population."

New COVID test: FDA grants emergency authorization for first COVID-19 breathalyzer test

Why isn't one shot enough?

From the start, COVID-19 was a serious concern because it's caused by a novel virus. No one's immune system had tackled it before.

To build an adequate immune response took two doses, studies have found, even with the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, which at first was promised to be a one-and-done shot.

Most vaccines do require several doses, including the shingles vaccine for middle-age and older adults, as well as childhood vaccines like ones that prevent polio, MMR and pertussis.

The seasonal flu changes so much that a new shot is needed annually to protect against whichever strains are likely to be circulating.

Most vaccines don't need regular boosters in adulthood (though tetanus is recommended to be given every decade) in part because the pathogens don't change very much, exposure in early childhood can train the immune system for life and because exposures to many of these diseases are rare.

Again, it looks like a healthy immune system may be set with just two shots against COVID-19, though time will tell. Offit thinks healthy people may need boosters just every two to three years, but since the vaccines have been around for about 18 months, their durability is not yet known.

A third dose provided extra protection against severe illness and death from the omicron variant, which is different enough from earlier strains that the immune system might need some extra help fighting it off.

Unfortunately, there's no clear-cut way to know whether someone who's been vaccinated or infected has adequate protection.

Dr. Jerome Adams, who served as surgeon general during the Trump administration, advocates using an antibody test called CovAb, for which he is a paid consultant. Adams said such a test, which costs as little as $13, can tell someone whether they still have any COVID-19 antibodies.

Although it's possible to fight off COVID-19 without antibodies, they are the first line of defense.

"If someone has no antibodies," Adams said, "that's who we need to make sure is getting a vaccine or booster."

How much protection does a COVID-19 infection provide?

Some people who've had COVID-19 say they don't need a shot because they're already well-protected. Studies have shown that infection provides broader protection than vaccination and probably lasts longer.

But not for everyone. Many people have caught COVID-19 more than once.

An infection that caused few if any symptoms may also lead to minimal protection.

And, as with vaccines, protection from infection fades with time, though probably more slowly. One recent study showed that on average, people who were infected were protected against subsequent protection for about 20 months.

The pandemic has now raged for more than two years, though, so even people with better-than-average protection who caught COVID-19 early on are likely vulnerable again.

The course of the pandemic

How a viral variant affects a particular country depends on several factors, such as vaccination rates and previous infections.

China now has more cases than ever. Omicron is so contagious that efforts to keep out the virus – incredibly effective earlier in the pandemic – are no longer working. Shanghai, a city of 26 million, is under total lockdown, but cases are still spiking.

The Chinese haven't been previously infected and the vaccines they use – which are different than the ones used in the U.S. – aren't as effective, so they're much more vulnerable right now than Americans are.

The highly contagious BA.2 variant now dominates in the U.S. as it does in the world, but it hasn't sparked a dramatic increase in cases here – at least not yet. If it doesn't, experts say we can thank relatively high rates of vaccination and previous infections, particularly the fact that so many people were infected a few months ago with some version of BA.1.

If it does take off here in the coming weeks, those who are vulnerable to severe disease if infected with COVID-19 should should more seriously consider a near-term booster, experts said.

But getting a shot now means that protection will fade by midsummer, and if there's an explosion of cases in the fall or winter, anyone vaccinated now won't have optimal protection.

Viral evolution

Changes in the virus will also dictate the booster strategy going forward, Monto and others said.

So far, the original vaccines have worked well to prevent severe disease and death from COVID-19. But as the SARS-CoV-2 virus continues to evolve, it is possible a new variant will emerge that won't be covered by the original vaccine.

Manufacturers are currently testing vaccines that target omicron specifically, or both omicron and the original virus, though it's not yet clear whether a different vaccine will be more effective.

"We realize you can't prevent everything, especially with an evolving virus," Monto said. "The need for revaccination will be dictated more by the virus than by us."

Next-generation vaccines will hopefully provide longer protection against more variants. But they probably won't be ready before the fall.

Dr. Peter Marks, who heads the FDA's vaccines division, said he viewed the recent authorization of a fourth dose as a "stopgap measure until we got things in place for a potential next booster."

He acknowledges that people are losing patience with boosters.

"We're going to have vaccine exhaustion – not immune exhaustion, but physical exhaustion" with repeated boosters, Marks said.

Can you have too many boosters?

It's not clear yet whether extra boosters carry risks. None has yet been seen, but there's a theoretical risk, Offit said, citing the example of the HPV vaccine.

Girls who received an early version of the HPV vaccine that prevents cervical cancer were well-protected against four strains of the virus. An improved vaccine spread that protection to nine strains.

But the girls who received the initial version, because their immune system had trained on those first four strains, weren't able to mount a strong response to the extra five, even with additional shots.

It's possible, Offit said, that getting too many COVID-19 boosters with the original vaccine could make it harder for the immune system to rein in a different variant, even after getting a variant-specific vaccine. But it's not clear how many is too many.

Even if there's no longer-term down side, he said, many people suffer fever or headache or other symptoms after each shot.

"We shouldn't have a cavalier attitude about booster doses," he said.

Another downside to authorizing so many boosters is the confusion it causes among the public, said Glen Nowak, former chief of media relations at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

"It makes them less willing to trust the recommendations," said Nowak, now a professor at the University of Georgia. "It's harder to credibly say that you're following the science, and people can see that."

Contact Karen Weintraub at kweintraub@usatoday.com.

Health and patient safety coverage at USA TODAY is made possible in part by a grant from the Masimo Foundation for Ethics, Innovation and Competition in Healthcare. The Masimo Foundation does not provide editorial input.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Second COVID booster shots are available, who should get one? When?