'People have the ability to heal and to let go. Healers help you with that'

For the record:

5:42 p.m. Sept. 27, 2022: An earlier version of this article said that Tello was part of a group of 90 men that established the National Compadres Network. The group had 19 men.

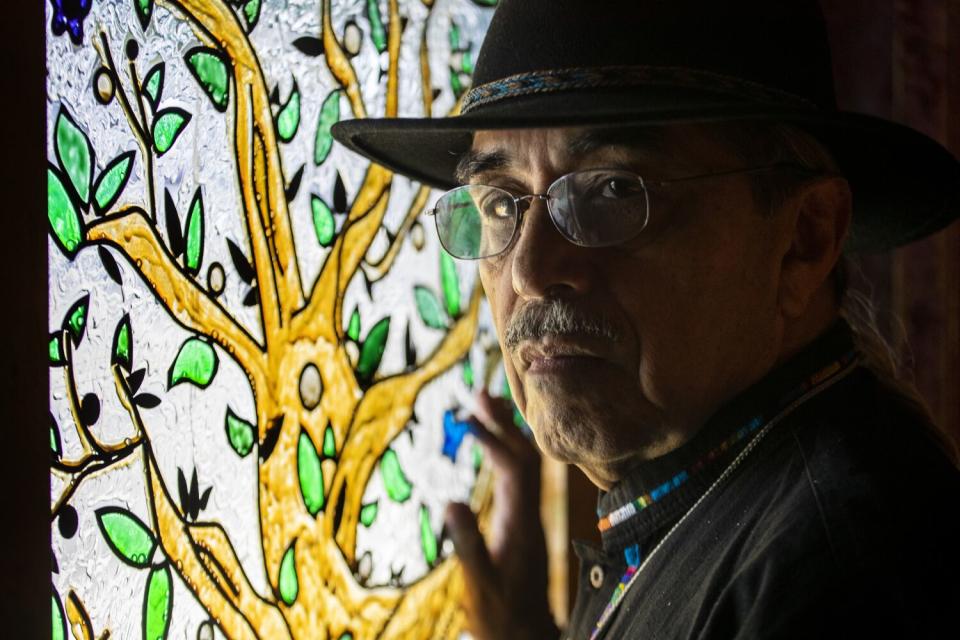

The home of the Sacred Circles Center in Whittier is inside a small white structure with blue trim. The building doesn't have a sign in front, but co-founder Jerry Tello says "the people that need to be here, will be here."

The center was created to be a place for people to come together and heal through presentations by Indigenous elders, culturally based healing and meditation circles, life coaching and family counseling.

The intimate space hasn't been used since the onset of the pandemic, but that hasn't stopped Tello and co-founder Susanna Armijo from continuing their mission of helping their community virtually, leading sessions via Zoom.

It's a calling that runs in Tello's family, which has Mexican, Coahuiltecan and Texan roots.

Growing up in Compton, Tello, 69, said he remembers his mother and grandmother helping their neighbors and friends through sobadas (Indigenous-based massage) or traditional herbal remedies. He also remembers his mother telling him not to talk about her healing work with teachers because it wasn't viewed as part of Western medicine.

This act of wanting to help others but facing the constraints of what's acceptable in medical and mental health practices was a turning point in Tello's service work as an adult.

He went to Cal State Dominguez Hills, earned his bachelor's degree in psychology and worked in community mental health clinics, including now-shuttered El Centro Mental Health. Even though he was able to assist people, he felt that following assessment and diagnoses protocol wasn't enough to meet his community's needs.

Tello and fellow therapists and community health practitioners, including a psychiatrist, began meeting to explore traditional Indigenous methods of helping the Chicano and Latino community; the group called itself Calmecac.

"We began exploring that, within our own culture, we had volumes that were written about healing, constructs, methodologies, philosophies, remedies and traditions that we didn't know about that our grandmothers used but that were not validated," he said.

This research, his college background, his clinical work and his experience of the Chicano and civil rights movements in Los Angeles pushed him to "explore effective ways [for] really healing, not just treating, not just intervening, not just medicating and diagnosing but truly healing our people."

In 1988, Tello was part of a group of 19 men who came together to establish the National Compadres Network — and its sister organization, the National Comadres Network. Their goal was to strengthen and re-root individuals, families and communities to honor, rebalance and redevelop the authentic tradition and Indigenous practices of Chicano, Latino, Native and other communities of color by integrating these cultural practices with Western-based mental health practices.

Since the creation of the organization, Tello has given keynote speeches, received awards (including the 2015 White House Champions of Change award) written children's books and the book "Recovering Your Sacredness," a guide to embracing traditions and wisdom — found in many cultures — that can help people return to their "sacred purpose. "

He regards himself as a healing practitioner, but the community has given Tello the title of "el maestro" (the teacher).

In the dimly lighted Sacred Circles Center, surrounded by drums used in healing circles, Tello sat down with The Times to talk about the place that traditional Indigenous healing practices have in the mental health field.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Regarding mental health, what does "healing the whole person" mean?

There is a word in my Indigenous Nahuatl language, Tloque Nahuaque,

which, loosely translated, means interconnected sacredness. In Indigenous thought, our sense of wholeness or well-being is a sense of us being physically, mentally, emotionally and spiritually balanced and harmoniously connected to ourselves and all our relations.

Western society basically looks at only the physical aspects of a person that may be manifesting mentally with certain symptoms. Their job is to address the symptoms — to take away the pain or discomfort.

In our traditional way, [healing practitioners] don’t separate the physical from the emotional, mental and spiritual. It’s all interconnected. So, from a healer’s point of view, we begin to look at all relationships and influences in your life.... It may not be just in your present life but the spirit of what you carry from your life journey ... what we refer to now as generational trauma. And from the spiritual, we talk about your meaning in life — how worthwhile do you feel as a man, woman or teenager? What’s your role?

Western society and its practitioners categorize people [so] they can determine a regimen of treatment to deal with the symptoms which, when added to the racial inequalities of the system, can create other issues. Not that Western health or mental health isn't necessary [sometimes], but it's focused more on treatment rather than healing.

From an Indigenous point of view everything is a teacher, a spirit, if you will. So we ask [about] what the "so-called" depression or anxiety tells us and where is it coming from. In an Indigenous point of view, those "spirits" can get attached to you and can become that overwhelming feeling. It also may be due to the "mal" bad energy that someone [has] projected on you and things that people have said about you that you are believing.

That may seem strange or mystical, but all of us have at one time or another been in a good mood, walked into someone's office who is in a bad mood and then walked out feeling all messed up.... It may necessitate a limpia —cleansing or the clearing of those burdensome thoughts or energy.

People have the ability to heal and to let go. Healers help you with that — help and support you rebalance and reconnect with the sacredness of who you are. But then it’s your job to maintain that. We may also reground you, bless you up (remind you that you are a blessing) through ritual, share healing stories, use healing songs [and] chants and give you some consejos [counsel or advice] of what herbs you can use and what practices to include in your life. Then [we] charge you with the responsibility to keep on the healing path.

How do you apply your clinical background in your traditional healing work?

We must recognize that this society is sick. The pandemic showed this. The racism, colonization, injustice and system inequities that exist in communities produce stress, trauma [and] fear and literally kill people. So, although individual intervention and treatment is important, healing at the community and societal level is imperative.

That is the work we do at the National Compadres Network. We have a major initiative [connected with the Sacred Circles Center] called the Healing Generations Institute to address the generational wounds that have been exacerbated by society on Black, brown, Asian, Indigenous and other oppressed populations by lifting up and integrating the generational medicine, teachings and healers that our communities have.

What would you say to people who know they need mental health care but fear using the system?

A lot of our people don’t trust the Western system — and with good reason. There were all kinds of horrible medical experiments done on people of color [like] the harmful eugenics movement. Many Indigenous people and people of color have been experimented on. Their bodies [were] mutilated and [they were] given medication and treatments.... Later on, [we] find that there are serious long-term side effects.

Research will show you that Black and brown boys are medicated for so-called ADHD at four to five times the rate of white boys. Why is that? This has been going on for generations and hopefully it's getting better, but then the pandemic comes and the inequities show up again.

There are also pharmaceutical companies that are controlling what kind of medications are out there and how much they charge, so we have capitalism that influences Western health and mental health. So of course there’s no trust — but I’m not saying that there isn’t a place for it.

Western medicine and conventional mental health has its place, for emergency situations and crisis situations. There are imbalances and illnesses that are so deep that the symptoms are interrupting the very functioning of the individual and causing tremendous discomfort. You need [that] medicine or certain clinical interventions to treat the issues.

And there are certain people that carry a very deep level of generational trauma [and] they may need to continue to use medications. But even then, it is important to consider the role of community healers and Indigenous-based practices and treatments, herbs, sobadas, limpias, sweat lodges and healing circles to continue the healing process.

How could our mental health system help more people?

Once you put a diagnosis on someone, it’s almost like you’re putting a spell on them. [If someone says,] "[You have] attention deficit," [you think]: “Oh, shoot, that’s what I am.” No, you’re not. That’s your woundedness, because you’re much more than that. Western science will label people and categorize them based on their woundedness. In [our] traditional medicine, we see their wholeness.

Maybe one of your wounds or cargas (your burden, or what you’re carrying) is alcohol. The alcohol can take over your spirit and we [as healers] understand that. In reference to alcohol ... it's no coincidence that they call alcohol a spirit. We know the substance or spirit of alcohol changes you. And the more it becomes part of who you are and what you do, that "spirit" can begin controlling you.

It is important in the most serious cases to recognize that ... you have invited that spirit to take over your life. Many people have "lost touch" with who they really are, but even in those cases, in order for them to truly heal, we must "call their spirits back" to the sacredness of who they really are and at the same time acknowledge the spirit of the substance that continues to challenge them everyday.

Unfortunately, Western treatment reverses the order and makes the disease their identity, as if they are nothing without the disease. A central part of Indigenous thought and healing is that the Creator and our ancestors are always present and our sacredness is always in us just waiting to be healed, blessed and released to do its sacred purpose.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.