At least 9 climbers died on 14,000-foot peaks in the US this year. These people do it anyway.

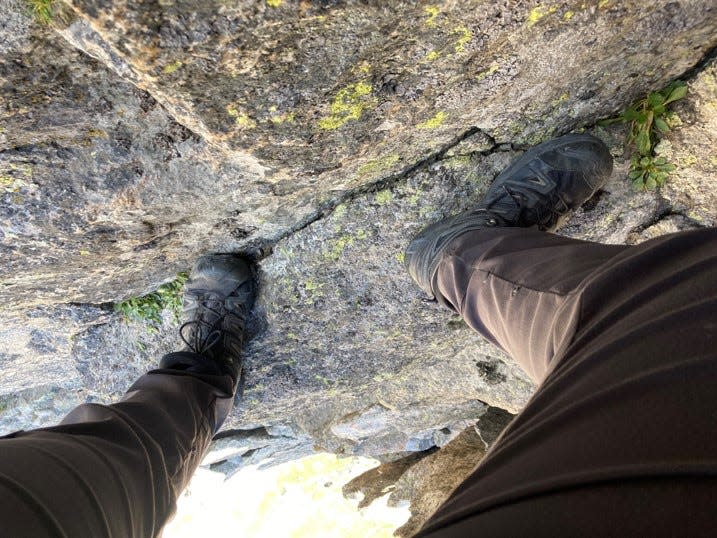

Shaking from the cold, Andreas Stabno clung to a narrow ledge on the face of a Colorado mountain ridge and cried as rescuers told him the news: six more hours until help arrives.

When the gathering dark clouds unleashed hail, Stabno called his wife and daughters. Then his sister and his mother.

"I thought this might be my last conversation with my family," said Stabno, 49, an experienced climber who frequently tackles peaks over 14,000 feet, also known as "14ers."

He hung on for hours until rescuers arrived. Stabno said the incident, this summer near McHenrys Peak, is forcing him to reconsider the dangerous pursuit.

Despite the risks, 14ers have exploded in popularity in recent decades. Climbing experts say population growth in Colorado, ease of access to online information and social media trends of posting photos from summits have fueled the rise, lending false confidence to amateurs and overwhelming trailhead communities.

"They're just getting more and more popular, and more and more people are jumping on the bandwagon of wanting to do all of the 14ers in the state," said Anna DeBattiste, spokesperson for the Colorado Search and Rescue Association. "The first thing is you really need to do your homework, especially if you're a newbie to the 14er world."

At least nine people have died on 14ers in the U.S. this year, according to Lloyd Athearn, executive director of the Colorado Fourteeners Initiative. The recent death of a Denver woman who fell from the summit of her final peak has once again drawn national attention to the increasingly popular activity and renewed the abiding question: Why do it?

Climbers with a range of experience levels told USA TODAY that the fatalities are a sobering yet unsurprising reminder that accidents can happen to even the most experienced climbers – and that it's worth it all the same.

TREACHEROUS CLIMB: Woman dies in 900-foot fall in Colorado

YOSEMITE IN PERIL: How climate change’s grip is altering America’s national parks

14er culture grows

Most of the peaks over 14,000 feet in the contiguous U.S. are in Colorado, followed by California and Washington. They range in difficulty; though some routes are accessible hikes, others are technical rock climbs.

Most people consider there to be 58 named peaks in Colorado, said Craig Brauer, 65, who helps manage a Facebook page dedicated to Colorado 14ers that has more than 52,000 members. But the exact number is up for debate, based on elevation drop and distance between peaks.

Many people start out with the goal of completing just one 14er but then decide to complete them all and start "peakbagging," said Brauer, who lives in Nebraska.

Most people who are physically fit can climb the majority of Colorado 14ers without encountering difficult terrain; it's the 15 or so most challenging peaks that pose the greatest risks, Athearn said. The peaks in California and Washington are generally harder and require more advanced skills, he said.

The Colorado Fourteeners Initiative formed in 1994 when there were only two planned 14er summit trails across the state, Athearn said. The group educates hikers, builds sustainable trails and monitors use with thermal counters in an effort to preserve 14ers. Now, there are at least 44 sustainable routes, he said.

In recent years, hiking on 14ers has been increasing about 5% to 7% annually, with some variation each year based on snowpack, air quality and more, Athearn said. In 2020, there was a "massive pandemic spike."

Rescues are up, too, DeBattiste said. Though the Colorado Search and Rescue Association doesn't have consistent statewide data on 14er rescues, incidents overall have been increasing steadily for decades.

"It would be an unusual summer in which there aren't any 14er deaths," DeBattiste said.

Six people have died on Colorado 14ers this year, which is "a bit above average," Athearn said.

Meanwhile, state and local governments and private landowners are increasingly discussing how to manage the flow of people to the mountains, Athearn said.

Some trailhead communities have made it harder to access trails. The number of hikers on Quandary Peak, one of the busiest, declined in 2021 after the county instituted a paid parking and shuttle system, DeBattiste said.

"However, it hasn't done anything to decrease the number of rescue calls," she noted.

Dawn Wilson, spokesperson with the Alpine Rescue Team, said some of the mountains in her area are like "Disneyland" on the weekends. She believes social media has glorified 14ers and led people to overestimate their abilities.

"It's all about getting to the summit and getting that picture," Wilson said. "If you see lightning and you're only 500 feet from the summit, turn around. Your life isn't worth an Instagram photo on the summit."

Wilson's team has started surveying people heading out at trailheads to ask if they have basic supplies, such as water or a headlamp. A majority are not prepared, she said.

Mountain Rescue Aspen has also seen a lack of education among climbers, said its president, Jordan White, 36. The Aspen area is home to many of the harder "finishers" for people attempting to summit all of the state's 14ers. White summitted them all by the time he was 20.

White encourages newer climbers to balance their motivations with their skill level and climb with a guide or group. Rescuers most commonly encounter people who are not prepared with the "10 essentials" or who have separated from their partner, he said.

"A lot of people that maybe in the past would have toughed it out and gotten themselves out are calling for help a lot earlier," White said. "We're all kind of wondering how bad it's going to get here when the iPhone 14 comes out here. You can satellite SMS from anywhere."

'People ask me why I do this'

People summit 14ers for various reasons: the views, the challenge and the feeling of accomplishment. For Stabno, who called for help on the ledge, it's a raw and spiritual experience.

Stabno, an actuary based in Lee's Summit, Missouri, attempted his first Colorado 14er in 1991. This summer, he started to climb his final three but turned back because of poor weather.

"People ask me why I do this. There's never been a good answer for it because it's kind of a dumb, silly pursuit. At the end of the day, the world is still the same," he said, pausing. "Well, maybe I'm not quite the same. Maybe I've changed a little bit."

Oanh Hoang, 29, a hospice nurse based in Basalt, Colorado, said she and her fiance started training for 14ers in February. They summited their first peak in mid-July. In September, Hoang summited her 12th.

Hoang said she has fallen in love with 14ers for several reasons: personal fitness, bonding with her fiance, the escape from the stresses of daily life. But her favorite part is sharing stories of her journeys with her patients.

"Every time I visit them, they cannot wait to ask me about my last climb and what's next," Hoang said.

Hoang said she knows every mountain has its own risks. So before every trip, she learns the route, watches the weather, checks her gear, assesses when to start and decides under what circumstances she would turn around.

"But with all that preparedness, a lucky element still plays a role," she said.

For Theresa Juliues Caesar, 39, summitting is a point of cultural pride. Originally from India, Juliues Caesar wore a saree on the top of Mount Columbia this summer and shared the photos in Brauer's Facebook group.

"Being a Tamil girl, the saree is my most favorite and important outfit. So I also want to honor my culture that I treasure," said Julius Caesar, a software professional based in Parker, Colorado.

Nikko Mowery, 45, a case manager based in Colorado Springs, said she started climbing 14ers a decade ago when a friend "dragged" her up one. "I was hooked right away with all the suffering and scenery," Mowery said.

She used to test her limits by doing longer hikes and timing herself. Now she’s focused on safety and building community.

"I like long hauls when my brain finally goes into zen mode. I also love meeting strangers online or on the trail – love exchanging life stories and worldviews," she said.

For Brauer, who started climbing 14ers in the 90s and has summitted all but six in Colorado, it's an activity to share with his son, Josh, 33. He was once descending Mount Sneffels when a rock broke off and trapped him in a narrow gully of snow, he said. His son got him out.

"Most people have stories like that because, even if you're an experienced mountaineer, things happen," he said. "And in my understanding, that's what happened to the gal on Capitol."

GO TAKE A HIKE! These 10 forest trails lure travelers nationwide

Everyone 'knows this is a possibility'

The Denver woman who died on Capitol Peak in September was trying to summit her "finisher" – the last 14er on her list. She fell 900 feet, and a nearby climber witnessed the fall.

The peak is particularly difficult. About 1,000 people climbed Capitol last year, and one person died, Athearn said. In summer 2017, five people died in what felt like a "tragic drumbeat" of fatalities, he said.

Family and friends gathered in Denver in Septemberfor a celebration of life for the woman, who was in her 30s. Friends shared photos and stories of her on social media pages and forums, mourning her loss but applauding her adventurous spirit.

The woman was an experienced climber, and there was "some unluckiness involved in her demise," said White, of Mountain Rescue Aspen.

"Everyone who does this activity, especially people who've done it a lot ... knows that this is a possibility — someone in the wrong place at the wrong time pulls on a rock that might have been there for millennia and comes loose," Athearn said.

Given the growing connectedness of 14er communities online, climbers nationwide are more aware of fatalities when they happen, White noted.

While Stabno has tried to detach himself from such stories in the past, he now finds himself more emotionally connected to accounts of strangers' accidents, he said. Earlier this summer, he spoke with a man on Crestone Peak shortly before the man fell to his death.

"Up until that point, it had never really been as personal to me," Stabno said.

In August, Stabno clung to mountain for more than six hours before he heard the "beautiful sound" of helicopter rotors. A rescuer descended from a rope and helped him into a harness. Finally, he let go.

Scarred by the incident, Stabno said he isn't sure he wants to pursue his three remaining 14ers. But he's not ruling it out.

"What really matters is our friends, our family and the relationships that we have," he said. "If we can keep those while we pursue our dreams and passions, all the better. If it jeopardizes some of that, I think we need to question what we're doing."

Reach reporter Grace Hauck via email or follow her on Twitter at @grace_hauck.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Colorado 14er death raises questions about climbing, safety