'People have to know what happened': Holocaust survivor, Guatemalan refugee share stories

PROVIDENCE – Ada Winsten was born into a life that was, even if only for a few years, comfortable.

In the rural Polish district of Baranowice, her father ran a lumber yard passed down to him by his father. The family had a cook and a maid. They went to spas. They wore nice clothes.

In September 1939, all comfort — and safety — was lost. Germany and Russia invaded Poland, and Baranowice came under Soviet power.

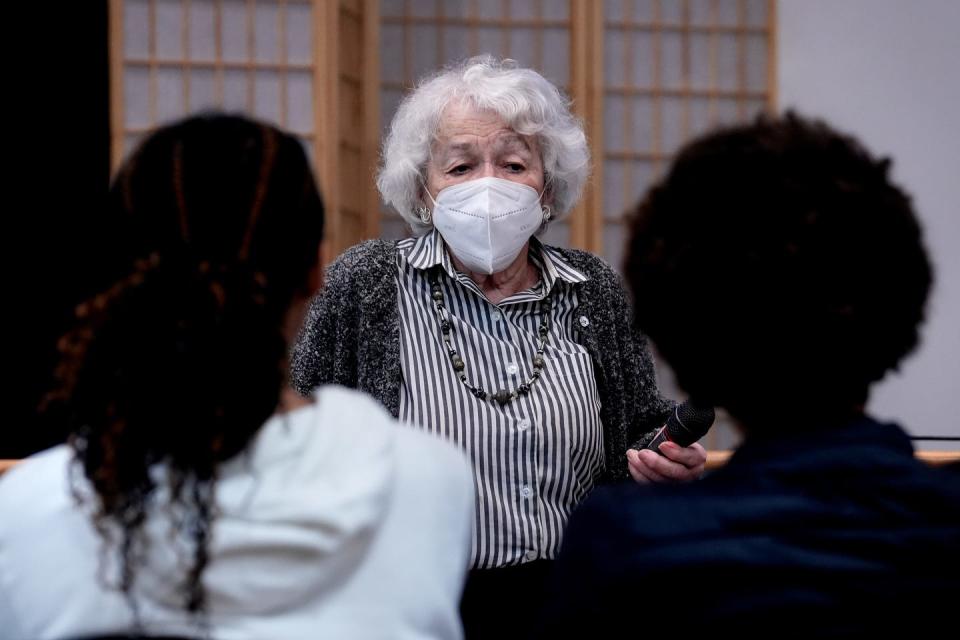

Standing before an audience of high-school students at the Sandra Bornstein Holocaust Education Center, Winsten recounted what it was like to survive the Holocaust. The talk was part of the center's newly launched Leadership Institute For Teens, intended to combat anti-Semitism in a world where it has grown. Hateful propaganda surged nearly 75% last year in Rhode Island, according to the Anti-Defamation League, and experts warned of extremist groups attempting to recruit in New England.

Winsten believes countering hate starts with the youth.

More:Antisemitic vandalism, harassment up more than 50% in RI. How that compares to the US

In today's headlines, reminders of the past

For Winsten, the past has come back to the surface through Russia's war on Ukraine, which just marked its first anniversary with combined death tolls for both sides pushing perhaps past 300,000.

"The way they walked into Ukraine, they walked into our house," Winsten said.

Russian troops gave the Winstens two weeks to move out, turning the house into their headquarters. By November, the family fled, unable to persuade relatives to join. It would take nearly 30 hours of walking before they would reach the Lithuanian border, where Winsten's sister fell on her knees begging soldiers not to shoot her family while her father fainted from the stress.

"It's amazing. No matter how far away these traumatic experiences are, we kind of still picture them in our head," Winsten said.

Eventually, with fake passports and a forged visa, the family traveled by train to Moscow, embarking on another trip to the port city of Vladivostok. There, they boarded a rickety ship to Japan that sank three voyages later. After a roughly eight-month stay in the city of Kobe, the Winstens arrived in Shanghai in August 1941. Winsten struggled to learn the language and said passersby pelted her with rocks. As a result, she conceded, she had developed a prejudice of her own, which she later worked to overcome.

Searching for any family left, Winsten's father sent telegrams inquiring about the family left behind in Poland. It wasn't until after the war that they realized just how many people the Nazis killed — including their relatives.

For nearly a decade, the Winstens were refugees. On Christmas Day 1948, they finally made it to the United States, landing in Anchorage, Alaska. From there, another flight and yet another train took them to a new home in New York City's Bronx borough.

Winsten, a social worker who later moved to Providence at age 21 after meeting the man who would become her husband, knows why she tells her story.

"People have to know what happened," she said.

'Back there again': She fled Nazis in 1939 near Ukraine and sees a replay in Putin's war

A modern refugee finds safety in Providence

Unlike Winsten, Nadia Escalante has lived in Providence for only 17 months. She arrived with her husband, two children, a 50-pound suitcase and a backpack. That was all she was allowed to take.

The family fled Guatemala as political refugees after Escalante's husband, who had a government job, refused to engage in corrupt activities and became the target of threats. So did his family.

"It was a nightmare," Escalante said.

She avoided telling her parents and stopped visiting them altogether, afraid they would become targets, too, if their address became known.

Escalante sought asylum in the United States, a process that was temporarily upended by the pandemic, though in 2021, she received an email. Her family had been accepted.

"That night, we were so happy, but at the same time we were so sad," Escalante said. "We were so angry."

The pain of being displaced from her home, a country she described as rich in nature, culture and good people, was acute.

Today, she has settled in Providence, and works as a coordinator for a clothing collection program at Dorcas International Institute of Rhode Island, an organization that aids refugees in resettling.

More:How RI immigrants are finding jobs and much more through nonprofit's contract with Amazon

Leadership program hopes to combat hate

Winsten and Escalante's visits are part of the leadership institute's first year operating. The program has brought together more than a dozen high-school students of different religions, races and backgrounds who will study not only the Holocaust but other genocides as well, and participate in leadership workshops.

For Zoe Weiss, a student at Wheeler School, the work is particularly timely.

"There's a lot of people who are denying the Holocaust now or who don't know about the Holocaust," Weiss said. "Our generation is the last generation who's going to be able to hear from Holocaust survivors, so I think it's really important for us to hear these stories so that we can educate future generations and prevent this from happening to Jews or any other marginalized group in the future."

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: RI Holocaust survivor shares story with Leadership Institute for Teens