People, places in Nashville that were a prominent part of Black history

NASHVILLE, Tenn. (WKRN) — From sit-ins at Nashville’s lunch counters to world-renowned musical performances, several people and places in the city have left a mark on history.

There are thousands of historical markers that can be found throughout Nashville and Davidson County, with many newer markers celebrating the contributions of Black Americans.

According to the Tennessee Historical Commission, the state’s marker program initially reflected the experiences and issues most relevant to a small minority — almost all male, white and affluent — with other important narratives missing.

However, in the years since, the marker program has been broadened to reflect the experiences of Black Americans, Native Americans, other people of color, and women. There are currently over 250 markers in the Nashville area that detail Black culture, stories and triumphs.

With the month of February recognized as Black History Month, it marks a time to look back on the experiences and contributions of Black Americans. Take a look at some of the prominent people and places that have been etched in Nashville’s history below.

William Edmondson Studio and Home

The site where this marker was placed is also where William Edmondson created renowned limestone sculptures in an open-air studio next to his home. Born in rural Davidson County in 1874, Edmondson made his home here in 1913 and began sculpting around 1932.

He was said to have drawn inspiration from his faith, community and nature. Many major museums acquired Edmondson’s work, and in 1937, he became the first Black man to earn a solo show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

Scholars consider him to be among America’s most important self-taught artists of the 20th century. The historical marker is located at the intersection of 14th Avenue South and Wade Avenue, next to the William Edmondson Homesite Park and Gardens.

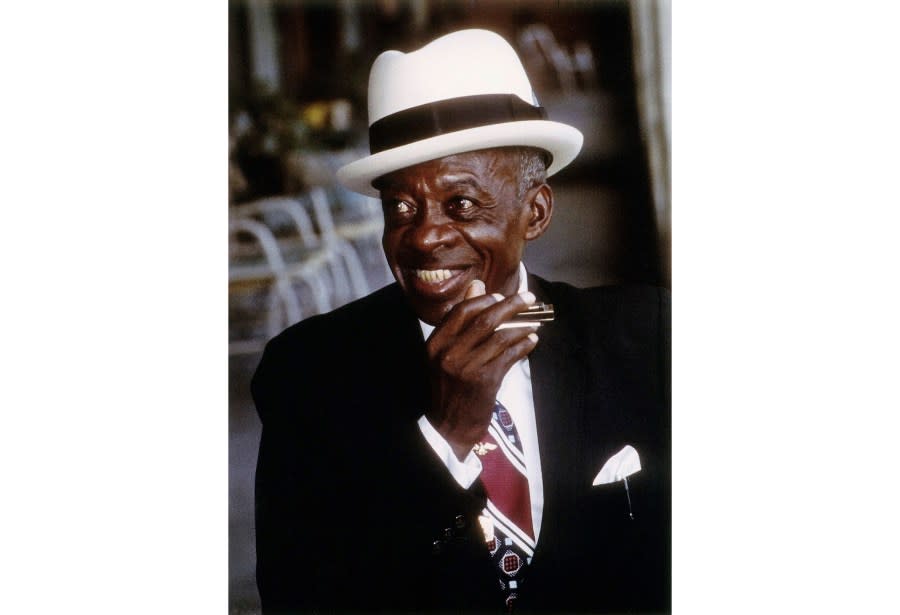

DeFord Bailey

DeFord Bailey was a pioneer of the Grand Ole Opry and its first Black musician. He lived in the Edgehill neighborhood for nearly 60 years and ran a shoe-shine shop on 12th Avenue South, near the intersection where this marker was placed.

Traveling extensively with Opry musicians, Bailey entertained audiences throughout the South and Midwest. It was his harmonica performance of the “Pan American Blues” that inspired Judge George D. Hay to dub WSM’s Barn Dance the “Grand Ole Opry.”

Historic places and people that helped make Nashville ‘Music City’

In 1928, Bailey recorded eight sides for RCA Victor during the first major recording session ever held in Nashville. The historical marker is easy to spot next to the Edgehill neighborhood’s iconic polar bear statues at the intersection of 12th Avenue South and Edgehill Avenue.

Z. Alexander Looby Home

This plaque marks the site of Z. Alexander Looby’s home on Meharry Boulevard. Looby was a prominent civil rights lawyer from the late 1930s until the late 1960s, and also served on the Nashville City Council and the Metropolitan Council.

He founded the Kent College of Law, Nashville’s first law school for African Americans since the 1890s and is credited with desegregating the city’s airport dining room and public golf courses.

Looby’s house was bombed on April 19, 1960, during a boycott of white-owned businesses to protest segregation in Nashville. However, he and his wife, Grafta, both survived the bombing.

In solidarity with the Looby family, around 3,000 civil rights activists marched on the Davidson County Courthouse later that day. By June, the seven downtown Nashville stores originally targeted with sit-ins and other protests desegregated their lunch counters.

Concern over the bombing of the Looby residence and the economic boycott helped achieve that result. The historical marker was placed on Meharry Boulevard, just east of 21st Avenue North.

Nashville Sit-Ins

On Feb. 13, 1960, 124 students from Nashville’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities walked into Woolworth’s, Kress, and McClellan’s, sat down at the lunch counters and asked to be served to no avail.

The students also targeted Walgreens, W.T. Grant, as well as Harvey’s and Cain-Sloan department stores. Their goal was to desegregate Nashville lunch counters. The student protestors experienced no violence until Feb. 27.

Behind the signs: 15 unique markers that detail Nashville’s history

On that day at Woolworth’s and McClellan’s, white resisters threw the students from their seats, punched, kicked, and spat on them. Nashville police only arrested the student protestors. In total, 81 students were arrested and charged with loitering and disorderly conduct.

Two days later, the court fined each student $50. They took a principled stand, refused to pay the bail, and spent a little over 33 days in jail. On May 10, 1960, Nashville became the first major city to begin desegregating its public facilities when six downtown stores opened their lunch counters.

The Nashville Student Protest Movement to desegregate all public facilities did not end until 1964. The historical marker was placed north of Church Street on Rep. John Lewis Way North, near the Woolworth Theatre.

Jubilee Hall

Less than five years after its creation, Fisk University was struggling financially, so in 1871, the school sent a nine-member student chorus on a fundraising tour of the northeastern United States.

On tour, the singers performed mostly popular tunes, sacred anthems, and patriotic songs, interspersed with spirituals. However, small audiences, meager donations, and the decision to gift what the singers had earned to victims of the Great Chicago Fire left the school right back where it had started.

Later that year, the group’s director, George White, decided that the group needed a name to grab attention and came up with the Jubilee Singers in memory of the Jewish year of Jubilee, a moniker that resonated with a biblical call for freedom.

From that point on, the Jubilee Singers successfully toured North America and Europe, with members traveling to England in 1873 to perform for Queen Victoria. By May 1874, the singers had raised enough funds to purchase land for a campus and construct Jubilee Hall.

The Jubilee Singers confounded critics who questioned the fitness of Black Americans for higher education and helped establish the spiritual as an authentic musical expression. Jubilee Hall, which was completed in 1876, is now a National Historic Landmark.

A historical marker commemorating the contributions of the Jubilee Singers is located in front of Jubilee Hall on the Fisk University campus.

Avon Williams Jr.

Avon Williams Jr. was an attorney, statewide civil rights leader, politician, educator, and a founder of the Davidson County Independent Political Council and the Tennessee Voters Council.

In 1950, as a cooperating attorney for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, he and attorneys Z. Alexander Looby and Carl Cowan filed and successfully litigated McSwain v. Board of Anderson County, the first public school desegregation case in Tennessee.

Williams was elected to the state legislature in 1968, becoming the first Black state senator from Nashville to serve as a member of the Tennessee General Assembly.

He represented the 19th district for more than 20 years, serving as a member of the 86th through 96th General Assembly of Tennessee. The historical marker commemorating his achievements is on Charlotte Avenue, just west of YMCA Way.

Jones School

In Brown v. Topeka and Brown II, the U.S. Supreme Court ordered public schools nationwide to end racial segregation “with all deliberate speed.” However, Nashville failed to comply for nearly three years, resulting in the Kelley v. Board of Education case.

As a result, in 1957, Nashville schools implemented a grade-per-year plan starting at the first grade until all twelve grades were desegregated. Four Black first graders were among the first to desegregate Jones School on Sept. 9, 1957.

A crowd of white segregationists taunted them, and many white parents removed their students from the school. However, members of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) visited parents in the area, supporting those already enrolled and encouraging others to join them.

By 1998, the court deemed the Metro school system to be desegregated. A historical marker can be found on 9th Avenue North, just outside of Jones Paideia Elementary Magnet School.

The Edgehill Community

Edgehill’s history dates from the decades before the Civil War, when country estates were located on and around Meridian Hill, now E.S. Rose Park.

The construction and defense of Union fortifications during the Civil War drew many African Americans to the area, where they contributed to the Union victory and the end of enslavement.

After the Civil War, they built the free communities of “New Bethel” and “Rocktown” that developed during the twentieth century into Edgehill. The neighborhood drew several residents through its schools, churches and thriving local economy.

Residents played vital roles in the Civil Rights Movement, and their advocacy included opposition to the adverse effects of urban renewal on the neighborhood. The Edgehill legacy continues to this day, with multiple historical markers celebrating its history.

Black Churches of Capitol Hill

This plaque is within less than a mile of six churches that stood in the center of Nashville’s prosperous Black business district before the Capitol Hill Redevelopment Program.

The churches include First Baptist Church (1848), Gay Street Christian Church (1859), Mount Olive Missionary Baptist Church (1887), St. Andrews Presbyterian Church (1898), St. John AME Church (1863), and Spruce Street Baptist Church (1848).

How Nashville’s once extensive streetcar system became a thing of the past

Several began before the Civil War as “missions” or Sunday School classes of earlier white churches. All boasted memberships of over 1,000 by 1910 and claimed the city’s most prominent Black business and professional families.

All but one moved in the 1950s, and all continue to serve the Nashville community. The marker is located at the intersection of Charlotte Avenue and McLemore Avenue.

Jefferson Street Music District

Nashville is known for its music, but one area of the city’s music heritage is today often forgotten. From the 1940s to the early 1960s, Jefferson Street was one of America’s best-known districts of jazz, blues, and rhythm and blues.

Famous Black musicians often played in the many clubs that lined the street. In 1962, one club, the Del Morocco, featured a house band fronted by a then-little-known musician named Jimi Hendrix, who went on to become one of the most celebrated rock guitarists.

Also on Jefferson Street, the Ritz Theater played host to a number of legendary names, including Duke Ellington. Other regular performers on Jefferson Street included Little Richard, Ray Charles, Fats Domino and Memphis Slim.

Many of the venues were later razed to make way for the construction of the Interstate Highways. A historical marker at the intersection of Jefferson Street and Interstate 40 commemorates the musical history of the area.

Preston Taylor

Preston Taylor was born a slave on Nov. 7, 1849, in Shreveport, Louisiana. He served as a drummer boy in the Union Army during the siege of Richmond, Virginia.

Taylor came to Nashville around 1884 and three years later purchased 37 acres of land at Elm Hill Pike and Spence Lane. A year later, he established Greenwood Cemetery, Nashville’s second-oldest cemetery for African Americans.

Retro Nashville | Ride the nostalgia wave through Music City’s history

A founder of the Citizens Savings Bank and Trust Company, in 1905, he established Greenwood Recreational Park, the first park for African Americans. Taylor was also among those instrumental in Nashville securing Tennessee A&I State Normal College.

Nearly 20 years after his death, the Preston Taylor public housing complex was named in honor of Taylor, who is remembered as one of Nashville’s most powerful Black leaders. A historical marker sits just outside of the complex on Clifton Avenue.

Engine Company No. 11

Organized on Jan. 15, 1885, Nashville’s first African American fire unit, Engine Company No. 4 was located at 424 Woodland Street. Multiple firefighters were killed on Jan. 2, 1892, while battling a fire that destroyed a full city block in the business district along 3rd Avenue North.

Funeral services for the fallen firefighters, Capt. C. C. Gowdy, hoseman Harvey Ewing and reel driver Stokely Allen were held in the State Capitol building that same week.

By 1923, Engine Co. 4 moved to North Nashville and became Engine Co. 11, before moving to its present location in 1966. The historical marker can be found at the intersection of Doctor DB Todd Junior Boulevard and 17th Avenue North in North Nashville.

Sarah Estell

Sarah Estell, a free Black woman in the slavery era, ran an ice cream parlor and sweet shop near where this marker is located on 5th Avenue North.

⏩ Read today’s top stories on wkrn.com

Estell overcame many hurdles faced by free persons of color and her business thrived. Her catering firm met the banquet needs of the city’s firemen, church socials, and political parties from 1840 to 1860.

Sampson W. Keeble

Sampson Keeble, a barber, businessman, and civic leader, became the first African American to serve in the Tennessee General Assembly. Serving from 1873 to 1875, Keeble was appointed to the House Military Affairs Committee and the Immigration Committee.

After service in the legislature, he was elected magistrate in Davidson County and served from 1877 to 1882. A historical marker commemorating his accomplishments can be found at the intersection of Broadway and 2nd Avenue North.

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to WKRN News 2.