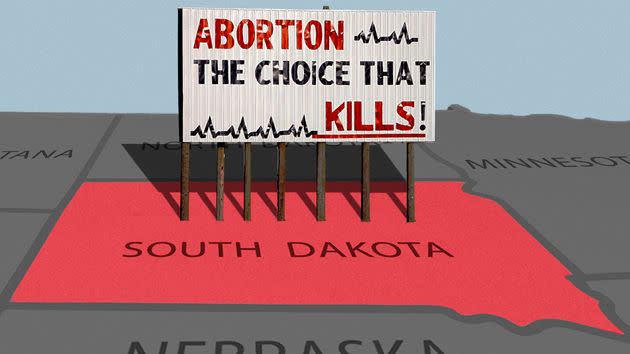

People In South Dakota Are Already Living In A Post-Roe World

More likely than not, you’ll find Sarah Traxler in an airport terminal, staring at her watch and wondering “When is this plane getting here?” Traxler, an abortion provider, flies from her home state of Minnesota to South Dakota twice a month to provide care in the last abortion clinic left in the state, Planned Parenthood’s Sioux Falls health center.

The center has been providing abortion care for South Dakotans for more than 20 years, but in all that time the clinic has never had an in-state abortion provider. Hospital systems in the state don’t allow physicians to work for them if they also provide care for Planned Parenthood. So Traxler, along with four other physicians, work on a rotating schedule ― each doctor takes one week a month, flying in twice that week to accommodate the state’s 72-hour waiting period for patients.

And each physician’s travel is scheduled down to the minute. South Dakota law requires patients seeking an abortion to undergo an initial in-person consultation and then wait for 72 hours before they can return for the procedure. Although many states have waiting periods, South Dakota is one of a handful that enforce such a long wait, and it’s the only state that doesn’t include weekends or holidays in that time. The additional hurdle here is that South Dakota law also requires the patient to see the same doctor on both visits.

That’s why Traxler’s timing is so critical. “Nothing can really start with the patients until my arrival, which is why I get so anxious. They’re all waiting on me,” Traxler told HuffPost in a conversation earlier this week.

Although South Dakota bans abortion after 20 weeks, Sioux Falls’ clinic offers the procedure up to 13 weeks and six days due to a law requiring out-patient procedures to have access to a blood bank, a rule that isn’t applied to hospitals. There are physicians who can provide abortion care later than that in the hospital system, but those procedures are rarely done and only in specific cases when the mother’s life is at risk or there are lethal fetal anomalies, and the entire process has to go through a hospital ethics board.

Traxler and her other four colleagues are essentially South Dakotans’ only option. A flight delay or winter storm could cost someone their short window to get an abortion.

Abortion access is already so limited in South Dakota that many people facing unintended pregnancies “are already living in a post-Roe world,” said Traxler. South Dakota’s long history of a Republican majority in its legislature has allowed it to routinely pass anti-abortion measures that slowly but surely have siphoned off access.

Abortion care is being threatened on a national level through a 2018 Mississippi law that bans abortion at 15 weeks and that is in direct violation of Roe v. Wade, the landmark 1973 Supreme Court decision that protects the right to abortion. Experts and advocates agreed that the court’s conservative majority signaled it would likely uphold the Mississippi law by either banning abortion outright or tinkering with the definition of fetal viability after December’s oral arguments. The lived experience of so many South Dakotans is about to become a reality for people across the country.

A Logistical Nightmare

Traxler’s schedule is time-stamped: Typically, she might fly in from Minnesota in time to arrive at the clinic at 11 a.m. on a Monday and see 12 to 15 patients. That same day she’d fly back to Minnesota and, three days later, do the entire process over again. If she arrives at the clinic any earlier than 11 a.m. on the second day, she can’t start seeing patients until those 72 hours between visits have been completed.

This causes a logistical nightmare for Traxler: If she misses her flight on Day One, her entire week is shot; if her flight is delayed on Day Two, she may not get to all of her patients, forcing her to restart the process for those who weren’t seen.

“It has a ripple effect where all of those patients who couldn’t be seen that week have to be rescheduled and do the entire process over again because the consenting procedures that I do with them on day one aren’t valid for the next physician,” said Traxler.

“There are times I feel personally responsible. Even if I’m sitting at the airport and the airline tells me my flight’s going to be three hours late, I think about if I can get in a car, I’m texting with the clinic manager and we’re trying to problem-solve,” she said. “It’s really hard. It’s sort of devastating when we end up not being able to make it.”

The burden on the patients is even worse. They have very little flexibility in appointment times, and the costs of getting to the clinic are doubled because of the two in-person visits requirement (the governor is currently trying to require a third visit). Sioux Falls sits in the southeast corner of the state, which means many patients are driving up to five hours to get to the clinic.

There have been several times when patients couldn’t make it to that second visit, recalled Traxler, who has worked at the Sioux Falls center since 2015. Sometimes it’s because a bad snowstorm has blocked the roads or because a patient has used all of their money on the first trip.

“I’ve had patients who look at me and say, ‘You mean I can’t have my abortion today? I’ve used all my money. I don’t know how I’m going to get back here on Thursday,’” said Traxler, noting that usually the clinic is able to rely on privately raised abortion funds that help pay for the procedure.

There’s one patient experience that has stuck with Traxler all of these years. A teenager, Traxler recalled, had gone through a judicial bypass ― no small feat ― to obtain an abortion.

“She came to see me on the first day, we went through everything, she was determined that she wanted to follow through with an abortion,” Traxler said. “She went the 72 hours, and then on the day that she was supposed to come back to the health center for her abortion, the principal of her school found out and refused to let her leave school. And she was unable to make it for her appointment that day.”

Traxler says it was deeply upsetting to her, the young woman and the clinic staff. They were able to work with the teenager to get her to come back a week later. “But, again, she had to go through the entire process from the start,” Traxler said.

From Bad To Worse

Like many GOP-controlled state legislatures, South Dakota’s is preparing for the fall of Roe sometime this spring. Ahead of the looming court case, South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem, a Republican opposed to reproductive rights, introduced a copycat of the most extreme abortion ban in U.S. history: Texas’ six-week ban that deputizes private citizens to enforce it by filing civil lawsuits. Noem is also preparing to finalize a September executive order blocking telemedicine abortions, which means in-person visits would be required to receive care.

If Roe falls, South Dakota has a so-called trigger law on the books, which would ban all abortions immediately. North Dakota also has a trigger ban ready, and other surrounding states, including Nebraska and Iowa, are set to introduce similar laws this legislative session.

“It’s already really difficult in the region, but depending on how legislation goes and how [the Supreme Court decision] goes ― we’re looking at a really tough map in the Midwest when it comes to abortion access,” said Emily Bisek, the regional director of strategic communications at Planned Parenthood North Central States.

Traxler tried to be optimistic, but she’s also a realist. She knows that soon enough her days as a traveling abortion care provider could be over: Patients in South Dakota will have to come to her instead. But not everyone can do that.

“It’s going to be pretty grim in South Dakota,” said Traxler. “We’re going to see an increase in the number of unintended pregnancies that are carried to term, and we’re going to see more people self-managing their abortions.”

This article originally appeared on HuffPost and has been updated.