‘People still get nervous when it rains.’ EKY town still struggles a year after flood. | Opinion

Tom King’s business has been flooded five times since 2016, so he knows high water. But the deluge that swept through Fleming Neon on July 28, 2022, was of a different magnitude altogether.

“The water in here was nine feet tall,” King said of his auto collision garage on Main Street. His business sits in front of a creek so tiny he doesn’t even know its name, but it swelled to an awesome size that night. “I lost 11 vehicles —three were up on jacks and just floated off and down the street. It took five and a half weeks of shoveling mud. It was a nightmare.”

The water — a rancid combination of mine runoff, sewage, and the ordinary chemicals of houses and businesses, was so toxic it ate through 20-ton chains. “Everything the water touched it destroyed,” he said.

He lost at least $100,000 in car paint and other equipment. FEMA officials came and talked to him, then said they couldn’t help. The Small Business Administration wouldn’t do anything, they said, because he’d filed an extension on his taxes. He got $10,000 from the Team Kentucky fund that he didn’t have to pay back.

“Thank God, I had some money in the bank,” he said.

For all this, King is not really complaining. He’s back up to his pre-flood rate of car repair, between 150 and 175 a year. He thought about closing or moving the business to Jenkins, but in the end, came back. And now he just hopes more of the empty storefronts — all of them hit by a wall of water — can reopen too.

“I hate to see them sitting there so empty,” he said. “This was already kind of a retirement community, and now a lot of people have left to go to Tennessee or South Carolina.”

It’s been a long year of very slow improvement for many people in Fleming Neon and in Letcher County, and many stories are the same: the endless haggling with FEMA or the SBA, rebuilding homes or trying to find new ones, the sharp prick of anxiety when rain drums on the roof in the middle of the night.

City Hall employees are still in a FEMA office trailer parked next to the high school football field because the real City Hall is on Main Street and is not yet habitable. Life requires constant resilience and patience and then a little more.

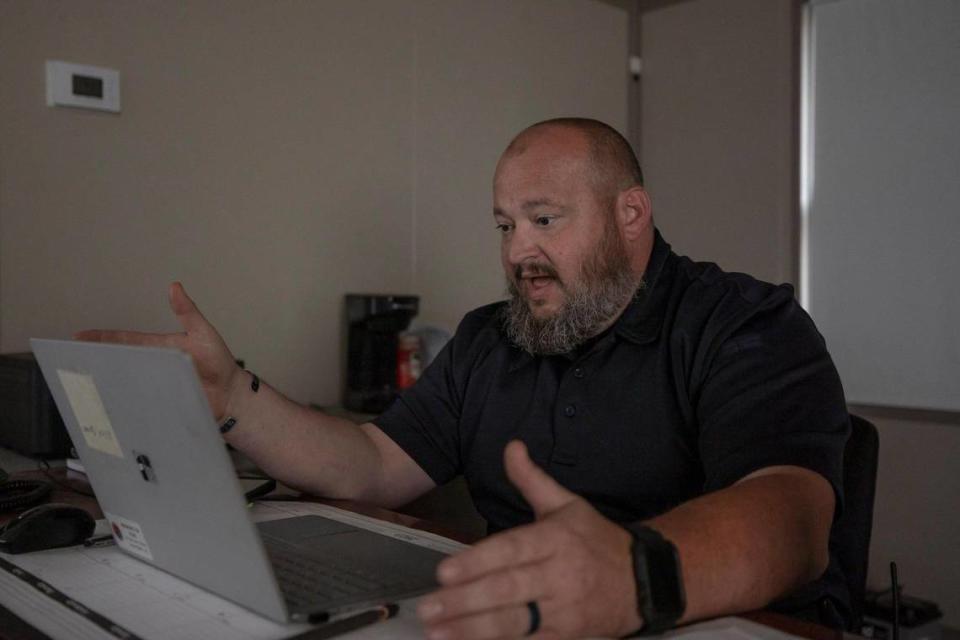

Police Chief Allen Bormes pondered what his community needs most on the one-year anniversary of such trauma.

“Hope,” he said after a moment, “if you could give that as a gift. We need a light at the end of the tunnel.”

The jewel of Main Street

One of the empty storefronts on Main Street used to be one of its jewels, a brand new public library, festooned with murals and filled with books.

The night of the flood, a tree turned battering ram crashed through the glass window of the back door. Water quickly rose to six feet along the walls. The space is now stripped back to the studs.

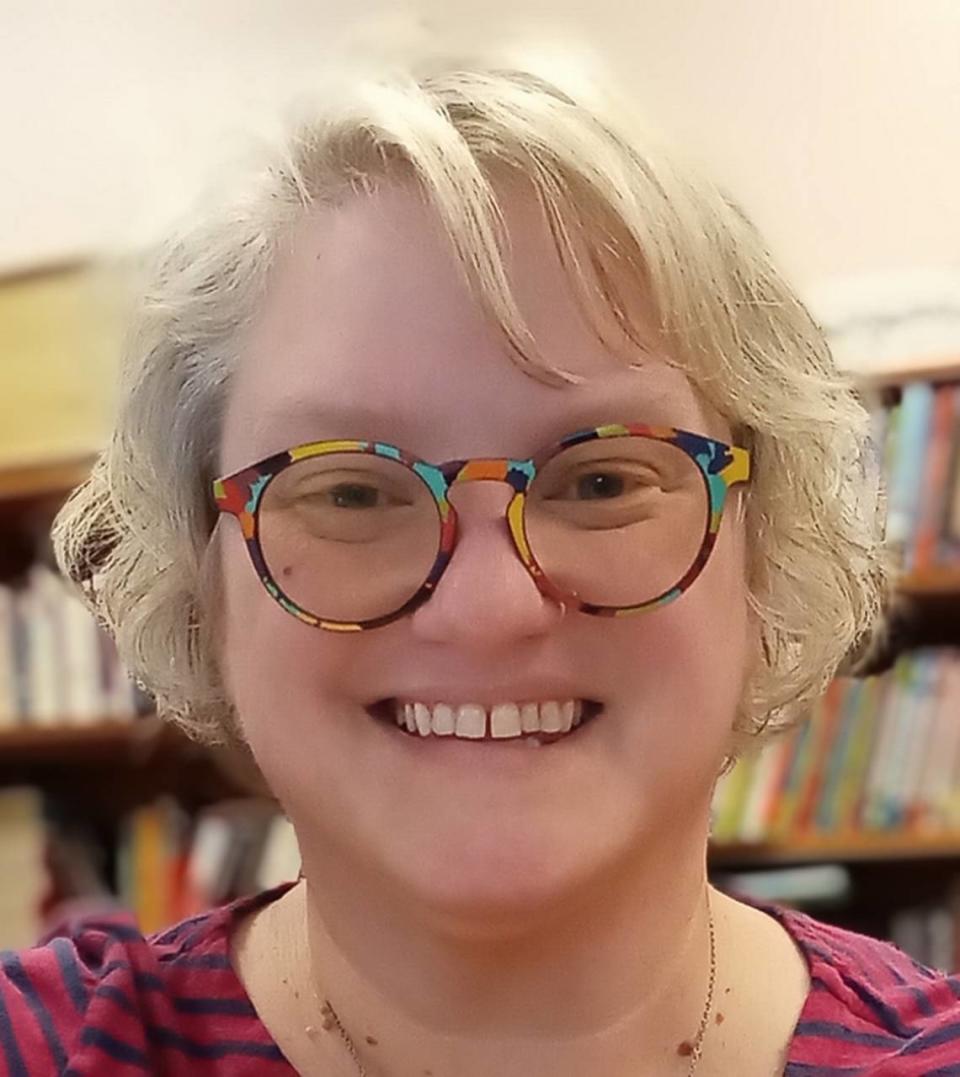

But the library will reopen, declared Alita Vogel, director of the Letcher County public library system.

Working with a “wonderful representative” from the Kentucky Emergency Management System, Vogel has now figured out that FEMA will pay for hurricane-grade windows and doors. She hopes construction can start by the beginning of October.

Three of the four Letcher libraries were flooded; Blackey and Neon are still closed. So much trauma and so much gratitude to the many people who helped makes for a complicated emotional afterburn. The system recently got a $40,000 grant from the Steele-Reese Foundation, which Vogel tells me about as she starts to cry.

“All of this still makes me very emotional,” she said. “It’s wonderful and it’s staggering how kind so many people have been, a year later I still end up crying about it.”

What the library does not need is more books. They’ve gotten tens of thousands of books, magazines and movies, so many they can’t afford to store them all, and have given many away.

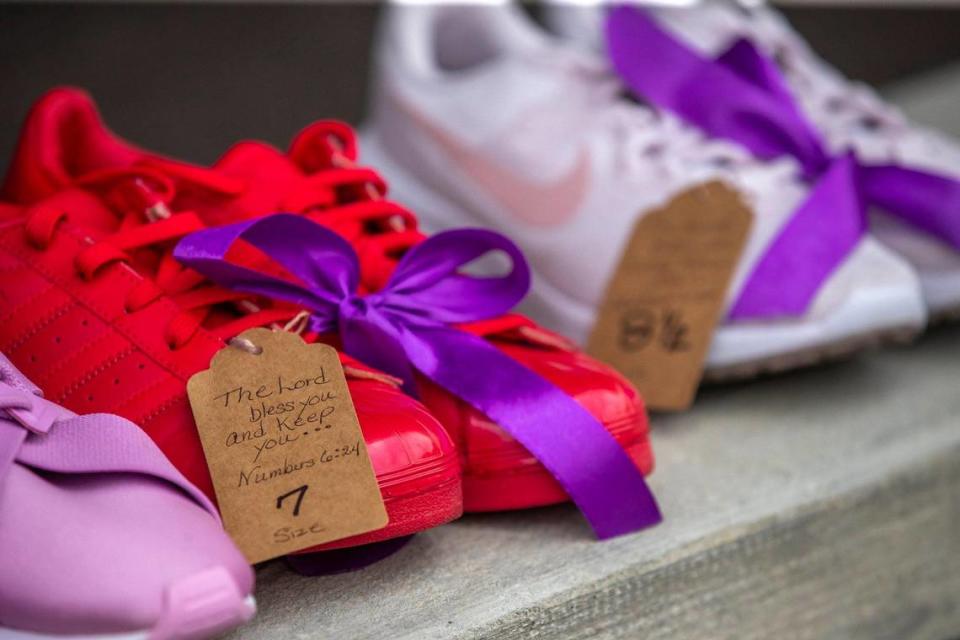

Behind the Neon Library, Lisa Wagoner is laying out sneakers in the carport of the Neon First Church of God. Someone who volunteered after the floods told his mother-in-law about Fleming Neon; she sent her sister’s sneaker collection to Wagoner to give away, sneakers with stripes and diamonds and ribbons and swooshes.

The church is a site for summer school meals. They serve 40-50 a day, which quickly disappear, along with the sneakers.

“We’ve had meals here for over a year and sometimes people just want to talk,” Wagoner said. “Most people are ok, but others are struggling a lot. When it rains at 2 a.m., it can trigger PTSD.”

Wagoner’s husband, Mark, is the pastor, and they just finished replacing the floors and walls of the sanctuary, but Wagoner is worried there won’t be enough people to fill them.

“This town was already dying,” she said. “What if there’s another flood?”

‘A hornet’s nest’

The man tasked with Fleming Neon’s recovery only started the job last year. Mayor Ricky Burke took office on Jan. 1, 2022; that night he was at the wastewater treatment plant working on superficial fixes himself to see if he could get it to work a little bit.

“He inherited a hornet’s nest,” Tom King said.

The floods exacerbated many neglected infrastructure problems in Eastern Kentucky, like Fleming Neon sewer and water systems, which still have an uncanny habit of sending raw sewage geysers out of manholes when it rains, according to King.

Entities like small towns apparently need liaisons to FEMA (call them anger translators if you like). Burke said he had to fire the first company, which delayed negotiations with the state and FEMA for the funding and permissions to fix those systems.

Now Nesbit Engineering is the go-between and things are moving along, Burke said, except the school district wants the City Hall trailer moved out of its parking lot. Burke has a full-time job in Whitesburg, so the stack of messages and problems to be solved are waiting for him every night and weekend.

“We have people with the biggest hearts and they love this place, our goal is to fill vacant buildings and get fully back,” he said. “But people still get nervous when it rains.”

The problem is it will rain again and it may even flood, and what will happen then in a place that already has struggles with jobs and depopulation?

Less than a mile up the road, Gwen Johnson runs the Hemphill Community Center which became a clearing center for flood relief, both supplies and people.

“We’re better than we were,” she said. But that’s a low bar.

Along with her neighbors, she’s gone to meetings of the Letcher County Long-Term Flood Recovery Group and leaves with more questions than answers. State funding and insurance money is a “politician’s dance,” she says, and it’s hard for regular people to understand the bureaucracy.

“The devastation was so bad and people are still trying to get their feet under them,” she said. Eastern Kentucky was already suffering from the end of coal, the scourge of opioids, the lack of jobs. And climate change that is sending 100-year floods a lot more often. If you are starting from behind, how do you get ahead of all of it?

“I don’t know,” Johnson said. “A year later we’re better but we’re not where we should be.”