Personal text messages in Mel Tucker harassment case called largely irrelevant by experts

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Fired Michigan State University football coach Mel Tucker dropped a bomb in the campus sexual harassment case against him when he and his legal team sent the media a trove of private text messages between the woman who accused him and her deceased assistant.

An Ingham County, Michigan, judge granted the woman – prominent rape survivor and activist Brenda Tracy – an emergency restraining order the next day, temporarily barring Tucker, his attorney and their associates from releasing more. A hearing Tuesday will determine whether the order should hold.

Tucker’s attorney touted the messages as evidence that Tracy had fabricated her allegations against Tucker. On social media, some echoed his claims, including a sports director for a TV news station in Lansing, Michigan, who proclaimed the texts proved Tracy had lied. The station fired her the next day and apologized to Tracy.

While the messages may have already damaged Tracy’s reputation in the court of public opinion, three of the nation’s top legal experts on Title IX and sexual abuse said the texts do not exonerate Tucker, who was accused by Tracy of masturbating over the phone without her consent.

Context, the experts consulted by USA TODAY said, is everything – and so far that context is missing from the subset of messages released.

“This is (Tucker’s) advocate’s presentation of a set of facts, so of course they are presented in what they hope will be the best light for Mr. Tucker,” said Patrick Mathis, an attorney and co-founder of Title IX Solutions, a consulting firm schools hire to conduct investigations and provide training and support.

“Would they stand the test of the (harassment case) decision-maker asking questions about them? Would they stand the test of seeing these comments and texts in a bigger text chain? Maybe not,” Mathis said. “It may look completely different.”

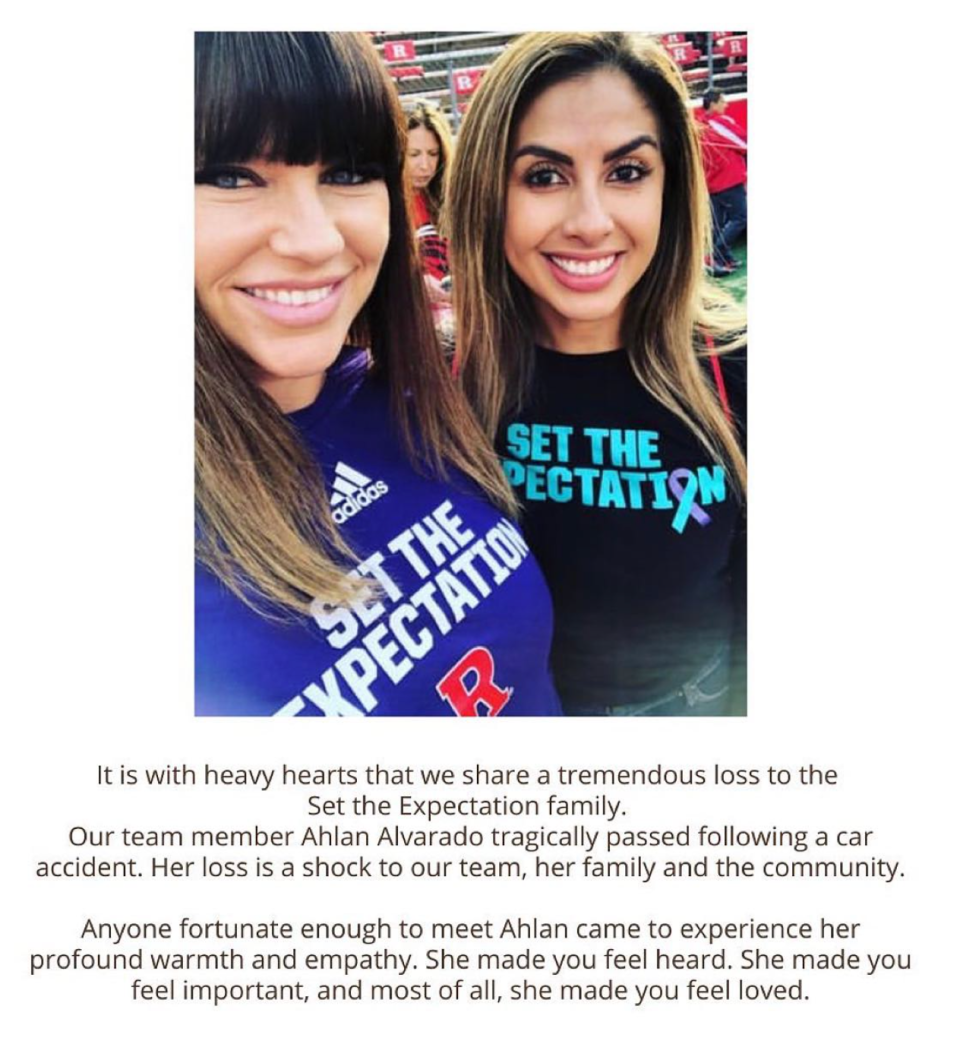

The texts released on Oct. 5 came from the cellphone of Ahlan Alvarado, Tracy’s friend of two decades and, more recently, her booking assistant, who died following a car crash in June. Among other things, the messages show that Tracy dated a coach who had hired her years earlier and that she was struggling financially when she filed a complaint against Tucker – all of which Tucker and his attorney called “key evidence” in the sexual harassment case.

Tracy’s civil lawsuit seeking the restraining order said the phone also contains confidential business records, personal information and highly sensitive discussions regarding sexual abuse survivors who interacted with her nonprofit, Set The Expectation. The judge’s order granting the request said Tucker appeared to have obtained the messages illegally.

Tucker’s attorney appears to have gained access to the cellphone through Alvarado’s widowed husband or another family member. According to Tracy’s lawsuit, Alvarado and her husband – Agustin Alvarado – were estranged and divorcing. It alleges he stole the phone from her estate.

The texts raise reasonable questions about whether Tracy’s story is as “clean” as initially portrayed, said David Ring, a California attorney who frequently represents victims of sexual harassment and abuse. But most speak primarily to Tracy’s character and personal life, he said, and only loosely relate to her allegations.

“All of this is a power play by Tucker to one, intimidate her; two, try to get her to back down; and three, make Michigan State think twice about trying to fight Tucker” in court, Ring said.

“I want to be so clear on this: None of these text messages that were released somehow prove Mel Tucker is innocent,” Ring added. “At the end of the day, all these text messages might be much ado about absolutely nothing.”

Will the text messages become part of the sexual harassment case?

For the texts to be considered in the campus case, Tucker would have to appeal the school’s decision and ask to admit them as evidence, a process that cannot start until the hearing officer issues her findings.

Three things could stand in his way.

Confidential and privileged information is generally only admissible in Title IX cases if the party who owns it consents to its release, Mathis said. If Ingham County Judge Wanda Stokes determines the messages are confidential or privileged, they might not be admissible in the university case without Tracy’s consent.

To admit new evidence on appeal, Tucker also must demonstrate it was unavailable when the decision was made and that it could affect the outcome, according to the school’s sexual harassment policy.

And Michigan State could determine that the messages are irrelevant because they are tangential to the central facts of the case, the experts said. Even if the school admits the texts, it could assign them little weight.

The phone call at the center of the sexual harassment case took place in April 2022, after Tucker had hired Tracy to speak to his football team about sexual misconduct prevention. Tracy said that by then, Tucker had pursued her romantically for months.

The fact that she was a university vendor, with an ongoing business relationship with the school, underpins both the college’s decision to investigate her complaint and the athletic director’s decision to fire Tucker on Sept. 18 – just over a week after Tracy went public with her allegations in a USA TODAY investigation.

Investigation: Michigan State football coach Mel Tucker accused of sexually harassing rape survivor

Tucker denies sexually harassing Tracy but does not deny masturbating during the call. In his version of events, he and Tracy had been in a romantic relationship and had consensual “phone sex.” That admission alone, athletic director Alan Haller said, was sufficient grounds for termination.

Tracy filed a complaint with the university’s Title IX office in December. The outside attorney the school hired to investigate completed her fact-finding investigation in July. A formal hearing took place over Zoom on Oct. 5 before a second outside attorney, who has until Oct. 25 to determine whether Tucker likely violated Michigan State's policy barring sexual harassment and exploitation.

Tucker and his attorney did not show up to the Oct. 5 hearing, saying Tucker couldn’t participate because of a “serious medical condition.” Instead, 14 minutes in, they emailed the media an eight-page letter addressed to the university’s interim president and Board of Trustees and 98 heavily redacted pages of Tracy’s text messages with Alvarado. The letter also said they had obtained testimony from a new witness they declined to name.

Tucker, his attorney, Jennifer Belveal, and Alvarado’s husband have not returned phone calls and messages. On Sunday, Tracy spoke to USA TODAY about Tucker and Belveal’s claims and shared additional context around the messages.

“These texts have nothing to do with the case,” Tracy told USA TODAY. “Tucker has had his opportunities to comply with MSU’s process, and he has refused to do so.”

Experts say Tracy’s private relationship is likely irrelevant

Tucker’s letter said the texts show Tracy had “simultaneous consensual personal relationships” with Tucker and a basketball coach.

In fact, while the texts indicate Tracy had a romance with a basketball coach, they do not show she had a romantic relationship with Tucker.

Tracy told USA TODAY she has been friends with the basketball coach since the 1990s and went on a few dates. She dated him again briefly in 2021.

“I have known him for many years and did not meet him through work,” Tracy told USA TODAY. “Tucker had no right to violate his privacy. Out of respect for (the coach), I’m not going to comment on this.”

Evidence and questions about a complainant’s sexual history are prohibited under MSU’s sexual harassment policy. And outing Tracy’s private relationship in a press release naming the man is unnecessarily vindictive, said Diane Rosenfeld, an attorney and founding director of the Gender Violence Program at Harvard Law School.

“That shows real desperation, as does the idea that they would skip the hearing and then, in the middle of the hearing, do this press release,” Rosenfeld said. “It’s just a publicity tactic.”

Belveal also wrote in the letter to the school that Tracy’s relationship with the basketball coach contradicts what she had previously told Tucker: that she does not date coaches. Tracy “repeatedly made these bold claims to falsely suggest that her relationship with Tucker was necessarily one-sided,” Belveal wrote.

The investigation report, however, does not indicate Tracy made that claim to the investigator. Rather, the report shows it was what she said she told Tucker when he asked during a November 2021 phone call if she would date him.

If Tracy merely recounted the interaction with Tucker to the investigator, it would not necessarily speak to her credibility, as Belveal claims, Mathis said.

“She could have just said that because she was trying to dissuade him from pursuing a relationship,” Mathis said. “That’s why I think the context of the actual interview is important.”

Tucker’s press release, Rosenfeld said, is the latest instance of his use of DARVO – Deny, Attack, Reverse Victim and Offender. It’s a tactic that those accused of sexual misconduct employ to influence juries and public opinion. Research has found it effective with those unfamiliar with it.

A close cousin of DARVO is the “nuts and sluts” defense, which Tucker and his legal team have also invoked, Rosenfeld said. It plays on common prejudices people have about victims, including that they are crazy, promiscuous or gold-diggers.

“It all becomes about her, and it’s never about him,” Rosenfeld said. “When we put the focus on her all the time, we’re never going to hold the perpetrators accountable.”

Anonymous witness’ claims don’t ‘carry much weight’

Tucker’s letter also raises the specter of a new witness who it claims has come forward with explosive evidence.

It says the witness stated in a sworn affidavit that Tracy and Tucker had consensual phone sex and had been in “some sort of relationship” at the time.

The letter didn’t disclose the person’s name, though in a footnote Belveal said Tucker would make the affidavit available to the Board of Trustees to review “should they desire to discuss this matter.”

If Tucker is serious about trying to admit this person as a witness in the case, that person will need to be interviewed by the investigator and cross-examined at a hearing, Mathis said. Until then, he said, it’s not really evidence.

“I don’t put much stock in it,” Mathis said. “Making a bare statement that there’s someone out there that is making these statements, to me, doesn’t carry much weight.”

According to the letter, the new witness also said that Tracy slept over at Alvarado’s house after her death and repeatedly asked family members for access to her phone and computers. Belveal wrote that this proved that Tracy intended to erase Alvarado’s phone to conceal evidence.

Tracy told USA TODAY that she asked for access to Alvarado’s computer for the same reason she filed for the restraining order: Because Alvarado was her employee, the computer contained business records she needed. Tracy said she did not intend to delete anything.

As for the phone, Tracy said she did not want to access it herself; she said she had raised concerns with Alvarado’s family members about whether Alvarado would want her husband, from whom she was separated, to have access to it.

“Even after her death,” Tracy said, “my friend has a right to privacy.”

Tracy sought funding for her nonprofit project

One of the more damning text exchanges, Belveal maintained in her letter, was one in which Tracy told her assistant that she would ask Tucker to finance a documentary project through her nonprofit.

“I’m gonna ask him to finance the doc part of it,” Tracy wrote in the Nov. 26, 2021 message. “He’ll do it.”

Earlier in the same conversation, Tracy mentioned the $95 million contract extension Tucker had signed with Michigan State that week. Those messages, Belveal wrote in the letter, show Tracy “had long been focused on counting Mr. Tucker’s money and was plotting to get some of it herself.”

Tracy told USA TODAY the project is a video-based learning curriculum her nonprofit has been building for several years. They planned to film engaging, documentary-style videos for the program, which she hoped teams and schools would adopt.

“Tucker on multiple occasions pledged to support my nonprofit financially and with resources, including introductions to people and companies,” Tracy said. “Tucker was just one of the people we are asking to support this project.”

Belveal also wrote in the letter that the texts contradicted another of Tracy’s statements to the investigator: that she would not accept gifts from Tucker after knowing he was romantically interested in her.

The investigation report, however, tells a different story. It shows Tracy told the investigator that she did not accept any “personal gifts” after Tucker asked her if she would date him.

Tracy also specifically distinguished between personal and nonprofit gifts, the report shows, noting she accepted a $2,500 donation Tucker made to her nonprofit in 2022 “because that was not a personal gift.”

Questions raised about discussion of settlement after the incident

Money also was at the heart of Tracy’s harassment complaint, Belveal’s letter maintains – a way to manipulate Tucker and the university for her own financial gain. Belveal cites texts in which Tracy discusses the prospect of settling the matter with Tucker or the school for money.

“Money is my only recourse to make him feel like there is a punishment,” Tracy wrote to Alvarado. “When they do the money I should make him pay me 10k directly.”

Tracy told USA TODAY the “10k” refers to the $10,000 speaking fee she lost out on when Tucker abruptly canceled her planned July 2022 campus visit to provide anti-sexual violence training to the football team. Tracy told the investigator she believes Tucker’s inappropriate behavior was the real reason for the cancellation.

In other texts, Tracy mentioned her own difficult financial straits, saying that her bank account was down to $5. Tracy has long dealt with financial hardships, including filing for bankruptcy in 2010.

“Any financial issues I’ve had have nothing to do with what he did to me or what I reported him for,” Tracy told USA TODAY. “He’s offered me money before and I have turned him down and not countered.”

It’s common for people who have been injured or harmed to discuss resolving the matter outside of court or the Title IX process, said Mathis, or for money to factor into the considerations. If the harassment occurred, he added, Tracy’s motivation for reporting it is irrelevant.

Belveal also argued that Tracy contemplating a financial settlement contradicted a statement she made to the investigator. According to the investigation report, Tracy told the investigator during a June 2023 follow-up interview that she had not mentioned money once in connection with Tucker’s behavior.

The investigation report does not capture the full context of what she said in her interview, according to Tracy. She says she was telling the investigator about two settlement offers Tucker and Belveal had proposed to her in January and March 2023 – after she filed her complaint but before Tucker sat down with the investigator for his interview.

What she told the investigator, she said, is that she never discussed money with Tucker and Belveal – a statement she stands by. In private conversations with her attorney and her friend, Tracy said she considered all avenues for a resolution and ultimately decided against settling, declining both of Tucker’s proposals.

Based on Tracy’s explanation, Rosenfeld said Tracy’s statement is “not really even an inconsistency.” To the extent the hearing officer might perceive it as a credibility concern, Rosenfeld said, she would have to weigh that against the numerous contradictions in Tucker’s accounts.

USA TODAY previously reported that Tucker changed his story and repeatedly misled the investigator about key facts, including his location during the April 2022 phone call – he said he was home but records showed he was in Florida on a university-sponsored trip – and why he canceled Tracy’s July 2022 visit.

“If you just apply common sense, who’s more credible in the situation?” Rosenfeld said. “I think (Tracy) wins on the common sense, hands down.”

Kenny Jacoby is an investigative reporter for USA TODAY covering sexual harassment and violence and Title IX. Contact him by email at kjacoby@usatoday.com or follow him on X @kennyjacoby.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Brenda Tracy's texts: What they do and don't show, and what experts say